Litigation Nation, Engineering Empire

A review of Dan Wang's new book Breakneck

This essay analyzes the big idea at the heart of Dan Wang’s new book Breakneck: that China is an “engineering state” facing off against America, the “lawyerly society.” Breakneck is well-informed, creative, and filled with wit. It also hinges heavily on vibes and intuition. Much of the intuition is compelling, but I wanted more data. So I assembled some. Inspired by Wang’s ability to fuse memoir with political-economy, the essay starts with an anecdote of my own and then gets into the data and analysis.

The Lost County of Wushan (巫山)

I ended up in Wushan on a whim.

It was 2024 and I had been staying in Chongqing, the World War II capital of China, for just over a month. Captivated by its cyberpunk aesthetic and multi-level streetscape, internet parvenus have lately been busy churning out a flood of near-identical videos like “The Biggest City on Earth You’ve Never Heard Of.”

Chongqing is, technically, the largest city on earth. But it is a “city” in name only: sprawling across 32,000 square miles, Chongqing would edge out Maine as America’s 38th largest state. While there, I decided to test Chongqing’s scale. From the city center, I hopped on one of China’s high-speed rail lines and rode out to the farthest county still within Chongqing’s jurisdiction (with an HSR stop). That put me in Wushan.

If waterworks and canals were once the marvel that “impressed the early modern European travelers [in China] more than any other,” today that distinction must belong to the country’s 42,000 kilometer HSR system.1 In less than two hours I was in Wushan, 500 kilometers from metropolitan Chongqing. By contrast, it takes 3 hours on Amtrak’s Acela to go 350 kilometers from NYC to DC—assuming, and it is not a safe assumption, that the train does not break down.2

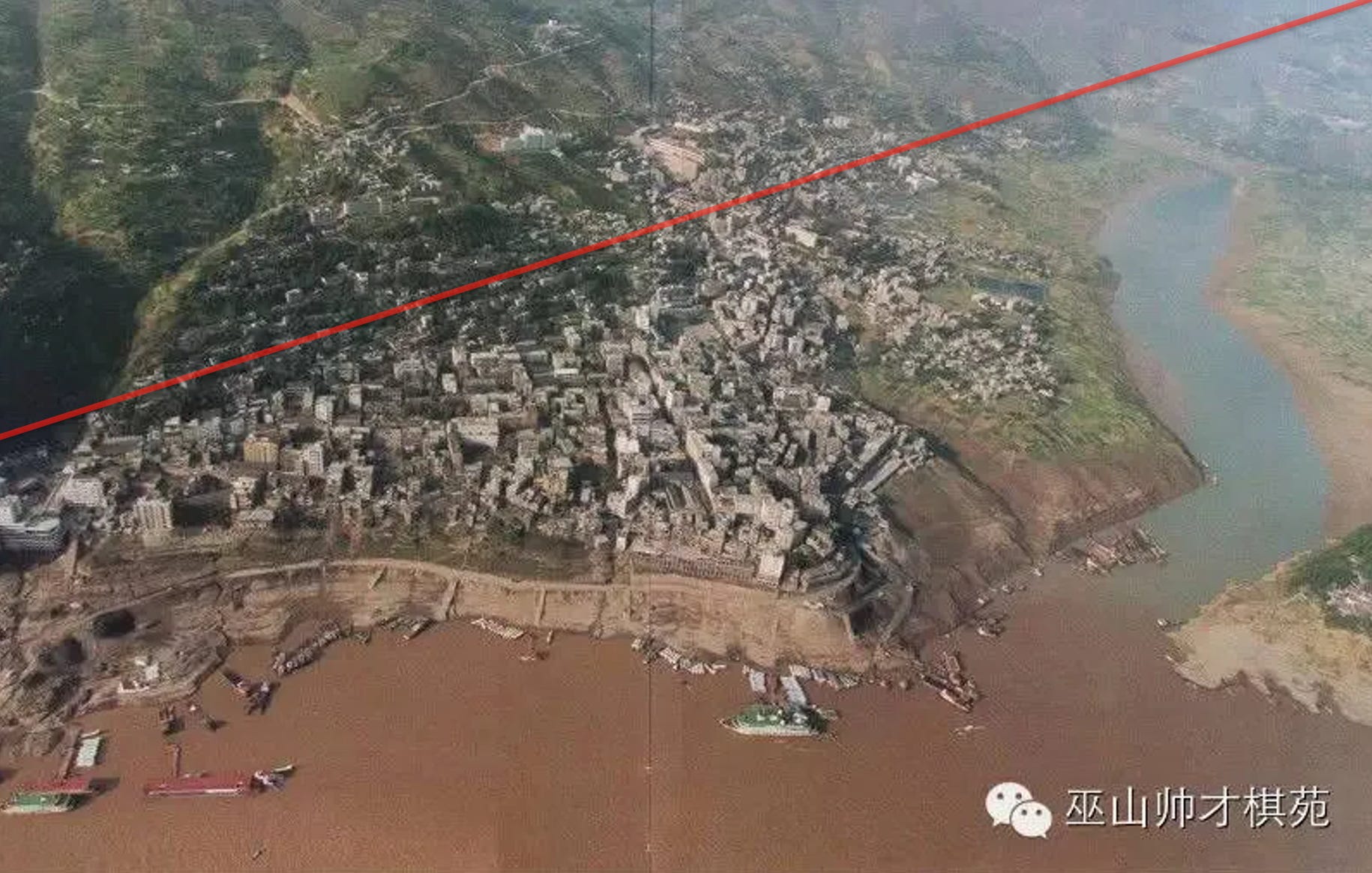

Stepping off the train in Wushan, the oppressive furnace of Chongqing—routinely hitting 105°F with very high humidity during my stay—gives way to air slightly softened by the area’s mythic mountain gorges. The county sprawls, but the county seat rests compactly on a steep hill that seems to rise straight from the water, perched atop the spot where the Daning river meets the Yangtze. A steep, grand staircase ascends from the river’s edge straight into the urban center above.

Wandering into town, I ask a man if people ever swim in the river. “Not really,” he misinforms me. A more enlightened fellow, overhearing, interjects. Locals gather at the base of the grand staircase around 6 p.m., after school and work. Off I go. It is a beautiful late summer evening as I arrive. Local kids and I have a swimming race as the sun slowly sets over the Yangtze.3

I knew next to nothing about the place prior to my arrival, aside from one thing: Wushan was not what it used to be.

Or, more precisely, it was not where it used to be. For we were swimming above the place it once was.

Swimming over what was once a city is a bit surreal—a sensation befitting a place called Shaman (Wu 巫) Mountain (Shan 山). At times I half expected to open my eyes underwater and glimpse a hidden Atlantis.

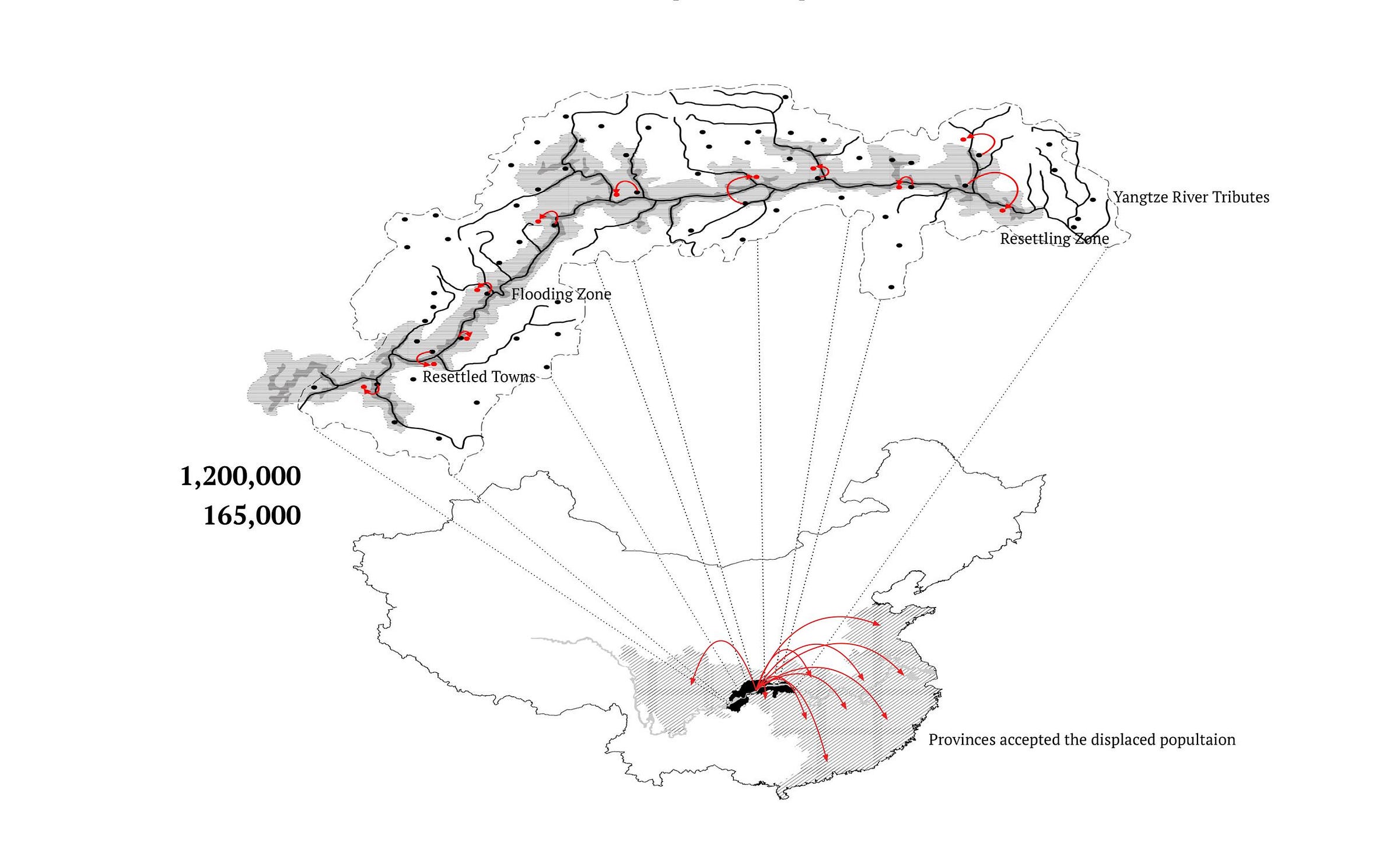

Wushan’s county seat was lost beneath the Yangtze as a consequence of the world’s largest dam: the Three Gorges. When the reservoir filled in the early 2000s, it swallowed 8 county seats, Wushan among them, and 116 towns. Over a span of hundreds of miles upstream, the river rose a staggering 100 meters, from roughly 80 to 175 above sea level.4 Had the Statue of Liberty stood where Wushan’s county seat once did, it too would have been fully submerged.

Before the dam, the Yangtze’s floods routinely swept eastward across the countryside—disasters that, over the centuries, claimed the lives of millions.5 The costs and benefits of building the dam have been debated endlessly.6 Not least of which was the 1.5 million so-called reservoir migrants (水库移民) who would be displaced—greater than the population of Estonia. Once the dam project was finalized in 1994, those in its wake had but one option: move. Or as the Party-state slogan put it “move out, settle down, and achieve prosperity.” The entire seat was rebuilt where I now found it: a hundred meters higher, still perched upon the Yangtze.7

Loss and rebirth is nothing new for Wushan. The county seat has ostensibly been burned down or destroyed by floods many times in its two thousand year history.8 In a way, rising above is routine, and fits with a certain view of Chinese building and time, as historian F.W. Mote summarized:

“Chinese civilization seems not to have regarded its history as violated or abused when the historic monuments collapsed or burned, as long as those could be replaced or restored, and their functions regained.”9

Or, as Simon Leys put it:

“The transient nature of the construction is like an offering to the voracity of time.”10

The loss of old Wushan could be considered an offering to the future. As difficult as the changes have been for many, they have likely been very positive on balance. In her 2002 book Before the Deluge, Deirdre Chetham describes her travels through the region just prior to its inundation. She wrote of Wushan as a hard place breeding hard people; one of China’s poorest counties, a river town known for its chaos—beset by street fights, ‘tearoom brawls,’ and even murders. For many, change, even the impending doom of their once home, was set against a new hope, embodied by a shining city upon a hill:

“Far above the riverbank, also visible from the river, is the new town of Wushan, where the city residents will move when the Yangtze waters rise. Located on the highest hill in the city, it shimmers in the distance, a brilliant white in a town where almost everything else is gray and brown. In Wushan, when people talk about the future, they point upward, gesturing vaguely in the direction of what will be left when everything else is underwater… For what might be called the middle class of Wushan, the educated and salaried people who work for the government, man the hospitals, write the newspapers, and run the hotels, the new city on the hill represents a future they want. It means that change in China is not just something that they see in a snowy TV newscast from Beijing but, they hope, an apartment with indoor plumbing and jobs for their children that might stop the exodus to Wanxian and factories in the south. It means, the wheeler-dealers think, a time when the houses they build will be sold on a private market and there will be people who can afford to buy them, and there will be an express bus to the center of Chongqing.”11

Today, over 20 years later, that hope for a better future seemed largely justified. Now firmly a middle-income county, the place feels relatively vibrant. Neon-lit building façades line the river and frame the main streets; in the evening people dance in the square, bathing in a technicolor glow from the evening light shows. And although the waterline is higher now, the scenery in the Gorges remains a sight to behold. (A video for context.)

One gregarious local I met while swimming spent the better part of a day darting me around on the back of his moped. We stopped at a village, swam across the river, and then he proudly took me along miles of pristinely paved new roads, showcasing the county’s recent transformations: a high-speed rail station completed in 2022 (the one I arrived and departed from), a number of bridges, and part of an expressway slated to cut the driving trip to Chongqing from five hours to three by 2029. It’s hard to escape the sense that the hopes of the residents Chetham once encountered have been met, if not well surpassed.12

Many kids in the county are nearly as stressed and overloaded with school and cram classes as their peers in China’s tier-one, -two, and -three city centers. There’s no college in Wushan, and a pressure to out-migrate to Wuxian or Chongqing remains. Come nightfall in Wushan, boredom sets in. Many wander the streets, restless, and searching for entertainment. In sharp contrast to the big cities, for quite a few my presence was one of the more entertaining developments. One evening, two high school kids stopped me and, after a chat, insisted on taking me to lunch the next day. They brought ten friends. We swapped questions. One boy, the group’s most direct, asked: “How many genders are there in America? In China we have two.” I replied: “Which of the two are you?” His friends were amused.

One thing that stayed with me was their response when I asked about their plans for the future. Nearly all happily declared an intent to go to college and major in physics, chemistry, or engineering.13

Tourist brochures insist no one can visit Wushan without feeling compelled to write poetry. Statues of 21 famous poets such as Du Fu and Li Bai line a prominent street. The natural beauty is indeed alluring. But as for me and the kids I chatted with, interest in poetry receded before beckoning feats of development and engineering.

Yu The Engineer

In a prominent local legend, the shamanic goddess Yao Ji, guardian of Wushan’s peaks, aids Yu the Great—first Emperor of the Xia dynasty and a legendary flood-tamer sometimes called Yu the Engineer—by quelling dragons that had been summoning torrential downpours, flooding the Yangtze river, and causing mayhem and destruction. In death the dragons took the shape of mountains, blocking the river’s eastward flow. Yu the Engineer set to work to save and marshal his people, recruiting them to split the mountains and dredge the river to create an eastern path for the water. Progress was terribly slow because his tools and techniques were crude, while floods and disasters stalked them constantly.

But, legend tells us, the shamanic guardian then bestowed upon Yu a divine flood-control manual (治水天书, “黄绫宝卷”). Within its silk pages were diagrams for hammers, chisels, wheelbarrows, transport boats—tools to dramatically increase the capacity to break and move rock and dredge channels. A cliff now called the Book-Giving Platform (授书台) is heralded as the location marking this celestial transfer of engineering knowledge. It is a myth befitting a hydraulic empire and a testament to man—or, more accurately, groups of corvée labor—and his ability to engineer the world around him.14 But the contributions of Yu the Engineer extend well beyond hydraulic engineering:

According to early accounts, his taming of the waters bolstered the centralization of state power, led to the creation of an empire-wide travel network, and established a system of tribute and taxation. Yu’s dredging and clearing were seen as civilizing acts that definitively inscribed the boundary between watery chaos and the (spatial and moral) order of a society grounded in agriculture and ruled by a bureaucracy.15

Legends that connect particular places to Yu the Great and other towering figures are endemic across the mainland. In the retelling, these stories have grown and changed, tending to create or reinforce narratives that serve the reigning authorities. In Science and Civilization in China, for example, Needham and his co-author’s suggest we can “find in the legends distinct traces of the connection of Yu with the origins of feudalism,” engineering myths thus mirroring China’s centralizing political evolution.16

The legends speak to China’s long-standing interest and experience in reshaping the material world on a monumental scale. From canal digging to terraforming, wall building to social engineering, no civilization possesses a longer history or memory of such undertakings.17 In 1997, Jiang Zemin rose to speak, his backdrop the rising scaffolding of the Three Gorges, and reflected on this theme:

Since ancient times, the Chinese nation has undertaken grand endeavors to conquer, shape, and harness nature. The legends of Jingwei filling the sea, the Foolish Old Man moving mountains, and Yu the Great taming the floods all embody the ancient Chinese people’s tenacious resolve that humankind can prevail over nature (人定胜天). Water-control achievements such as the Dujiangyan Irrigation System, completed more than two millennia ago, and the Grand Canal, greatly expanded and unified in the Sui dynasty, have left a lasting imprint on China’s economic and social development. Today, in the Three Gorges of the Yangtze River, we are building the world’s largest water conservancy and hydroelectric project, with the broadest and most far-reaching benefits of any such work in history, an enterprise that will powerfully spur our nation’s development. It is a monumental undertaking that will benefit the people of today and bless countless generations to come, embodying the industrious, resilient, and self-reliant spirit of the Chinese nation, and expressing the bold ambition of the Chinese people, in the era of reform and opening, to transform the land and create the future.18

Yu the Engineer now tends to serve as something of an allegory to national power. A massive statue park in Wuhan is demonstrative (pictured below). Built in 2006, the same year the Three Gorges dam was completed, it is also an homage to the potency of the Party-state, which had just replicated Yu’s legendary and “superhuman feat of quelling the floods” of the mighty Yangtze.19 Bearing witness to such development, is it any wonder the youth of Wushan are jazzed on the world of atoms?

The People’s Engineering State of China

I thought of the lost county seat of Wushan as I read Dan Wang’s new book Breakneck, and of how well Jiang Zemin’s speech in the shadow of the Three Gorges reflects its subtitle: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future.

Wang opens Breakneck with his story of cycling from Guizhou to Chongqing. Guizhou is often trotted out as a poster child of China’s “over-investment.” Remote, mountainous, and still among the country’s poorest provinces, it is nonetheless filled with engineering marvels: 45 of the world’s 100 tallest bridges grace its valleys. It was this new infrastructure that made his bike journey possible. He notes the locals “were prouder of their bridges than anything else” (p. 27). He nods at the very real debt overhang, as I have. But the author’s overriding impression—whether in Guizhou or Chongqing—is similar to mine: despite much waste, overall the building has been worth the while.20

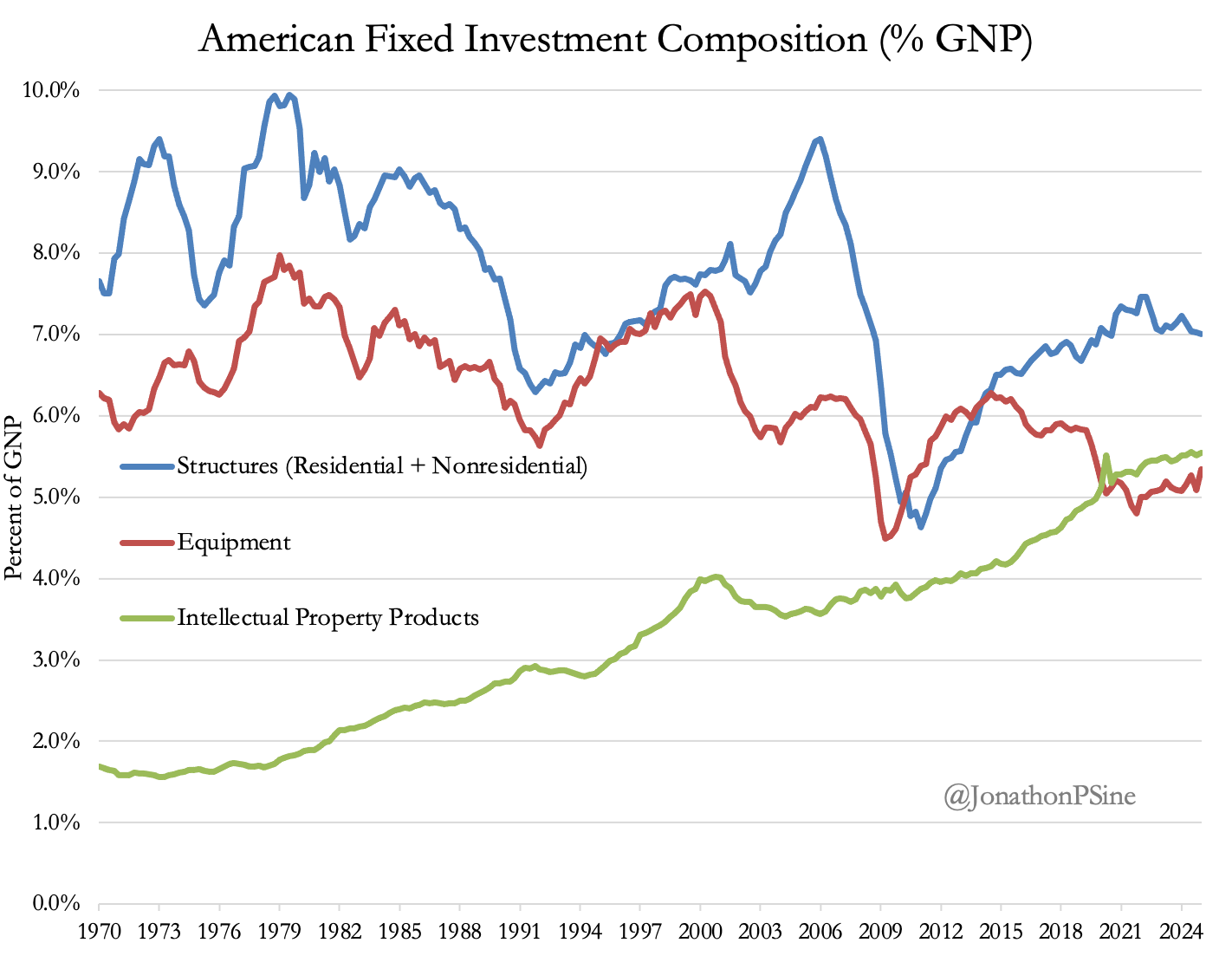

If China has allegedly overbuilt, then America has under built. Whether housing, infrastructure, or business capital expenditure: development of the built environment too often feels stagnant. One big piece of evidence: investment in equipment and structures as a share of American GNP is down 3 percentage points from where it was in the 1970s.

All of this relates to Dan Wang’s “big idea” in Breakneck:

“China is an engineering state, building big at breakneck speed, in contrast to the United States’ lawyerly society, blocking everything it can, good and bad.” (p. xv)

The “engineering state” label captures something real. It almost evokes Karl Wittfogel’s “hydraulic empire.” And the term speaks not only to China’s deep history as a nation obsessed with transforming the material world, as embodied in legends such as those surrounding Yu the Engineer, but also to the realities and fixations of the current rulers: a Party-state that dreams big engineering dreams, and which sometimes turns them into social engineering nightmares.

Prosecuting the Case: “Engineering State” vs. “Lawyerly Society”

The book never really defines the contours or empirically tests the “engineering” vs. “lawyerly” frame. The author notes of “engineering state” and “lawyerly society” that he aims to be “inventive and even playful with these terms,” as opposed to rigorous and pedantic. New ways are needed, Wang argues to “think about how both countries function and how they fail,” that are not merely “amalgamations from political science texts.”

In true American spirit, I will be a bit lawyerly about prosecuting how well these labels fit and whether they do a better job than existing terminology.

What, for example, constitutes “engineering” in Wang’s sense? Must one be formally trained, or can any kind of technical-administrative training and work experience produce an engineering mindset? And “lawyerly”—does that refer strictly to law graduates, or to a broader proceduralist habit of mind found among social scientists, policy professionals, and administrators? The book offers few definitions or empirical tests. In terms of impact, what are the pathways by which engineers and lawyers ingratiate themselves into the halls of power, or more broadly influence state and society? Must they be members of the elite (corporate and government) or is there a broader ethos that diffuses from their sheer numbers? Again, little by way of specifics.

So, as a start, I compiled some data.

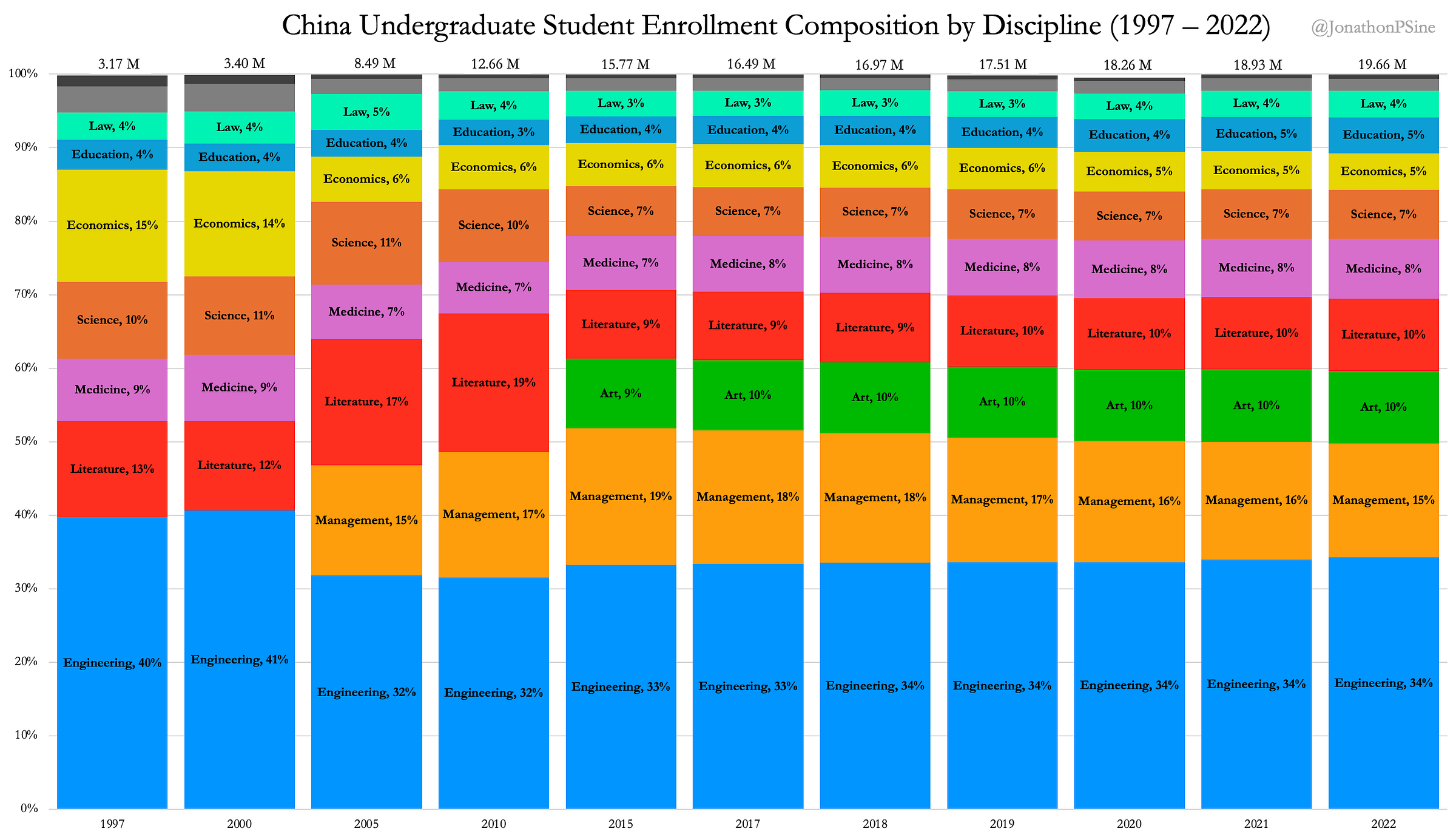

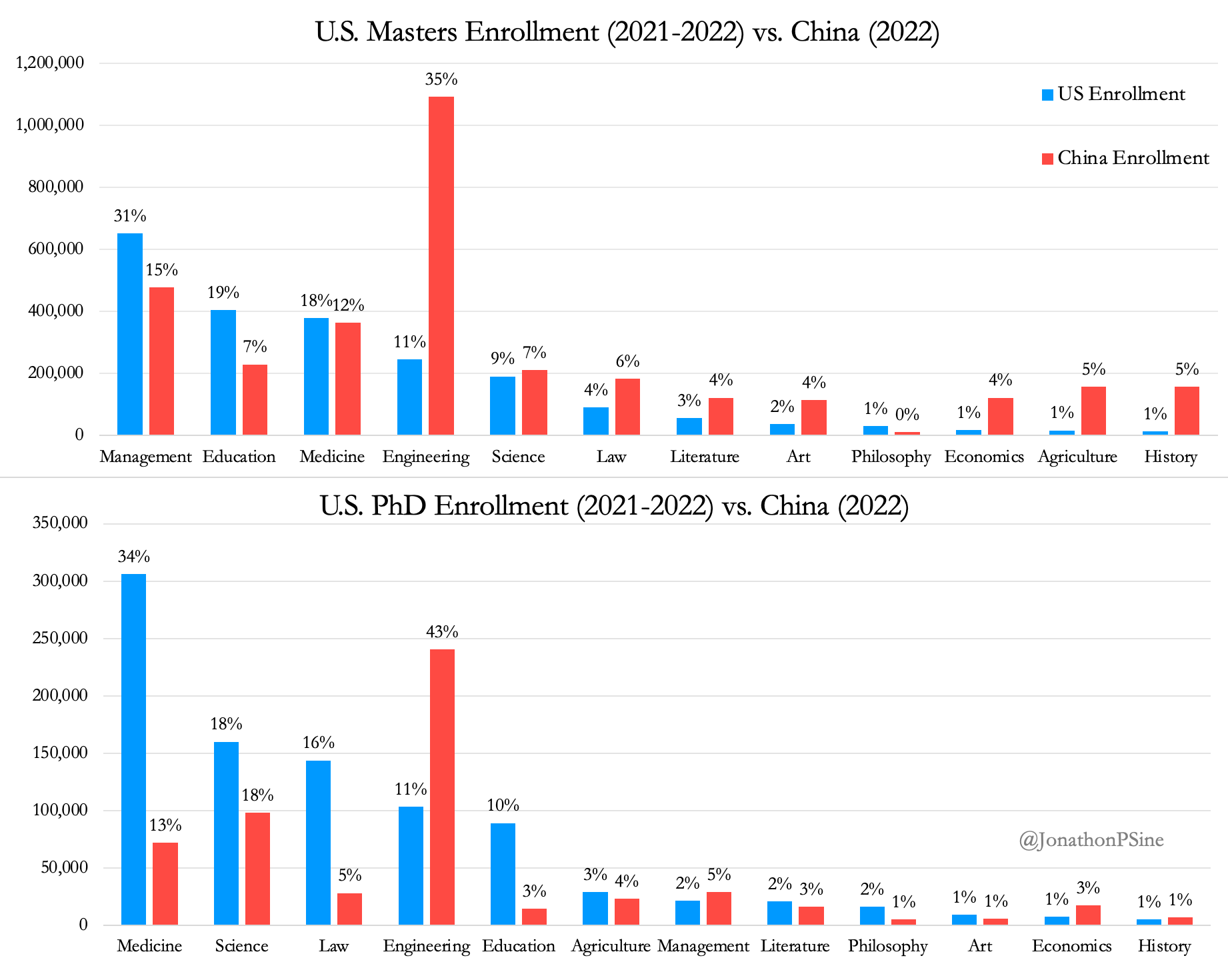

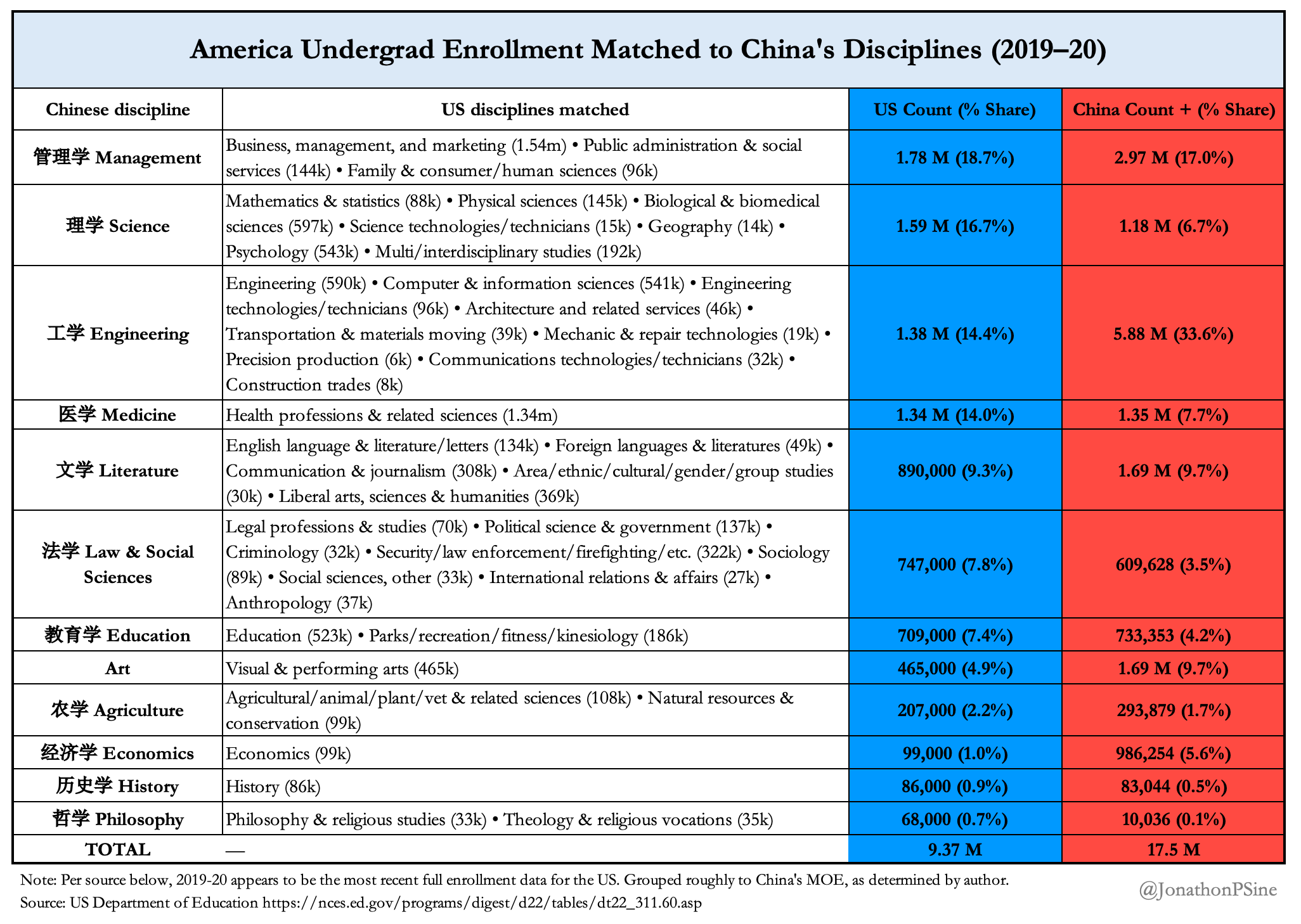

Today, China’s undergraduates overwhelmingly continue to choose engineering as their major (34%), down slightly as share from the 1990s but likely due to reclassification (creating a management discipline). Over that same period, China experienced an unprecedented explosion in undergraduate enrollment: from 3.17 million students in 1997 to 19.7 million in 2022. While questions remain about quality, the old Napoleon line applies: quantity has a quality all its own. In a year, there are nearly 7 million undergraduates studying engineering in China (mostly mechanical, electric, and civil).21 The closest competitor is management (管理学) at 3 million (15%).

And even as enrollment has grown, the split between humanities / social sciences (philosophy, economics, law, education, literature, history, art) vs science / engineering (science, engineering, agriculture, medicine, management) remains roughly one-third to two-thirds. And the funniest stat: Engineering: 6,742,664 vs. Philosophy: 12,400.

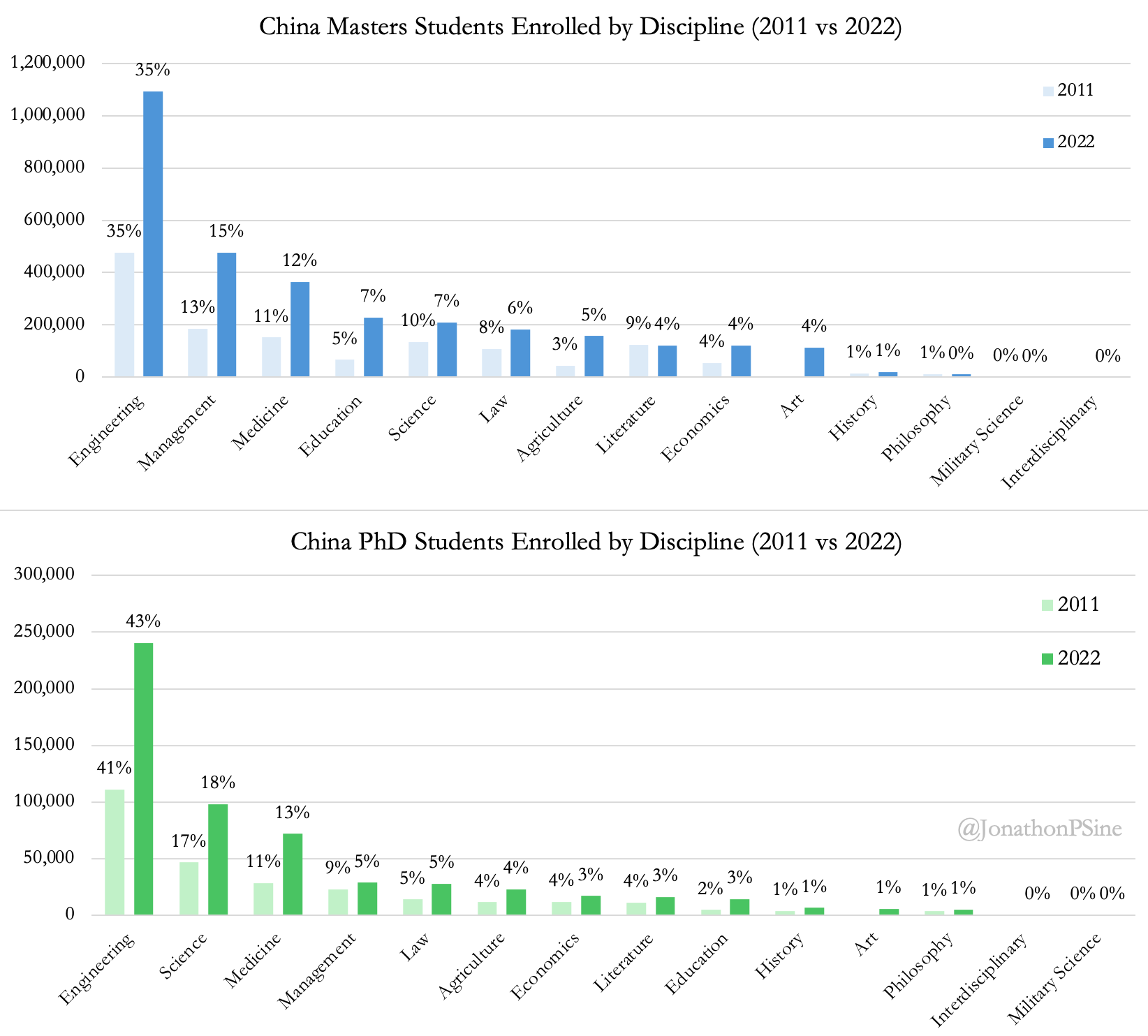

The engineering tilt is even more intense at the graduate level. The data below compare the evolution of masters and PhD enrollments between 2011 and 2022. Over 43% of China’s 556,000 PhD students in 2022 and 35% of China’s 3 million masters students were studying engineering, both up from 2011.

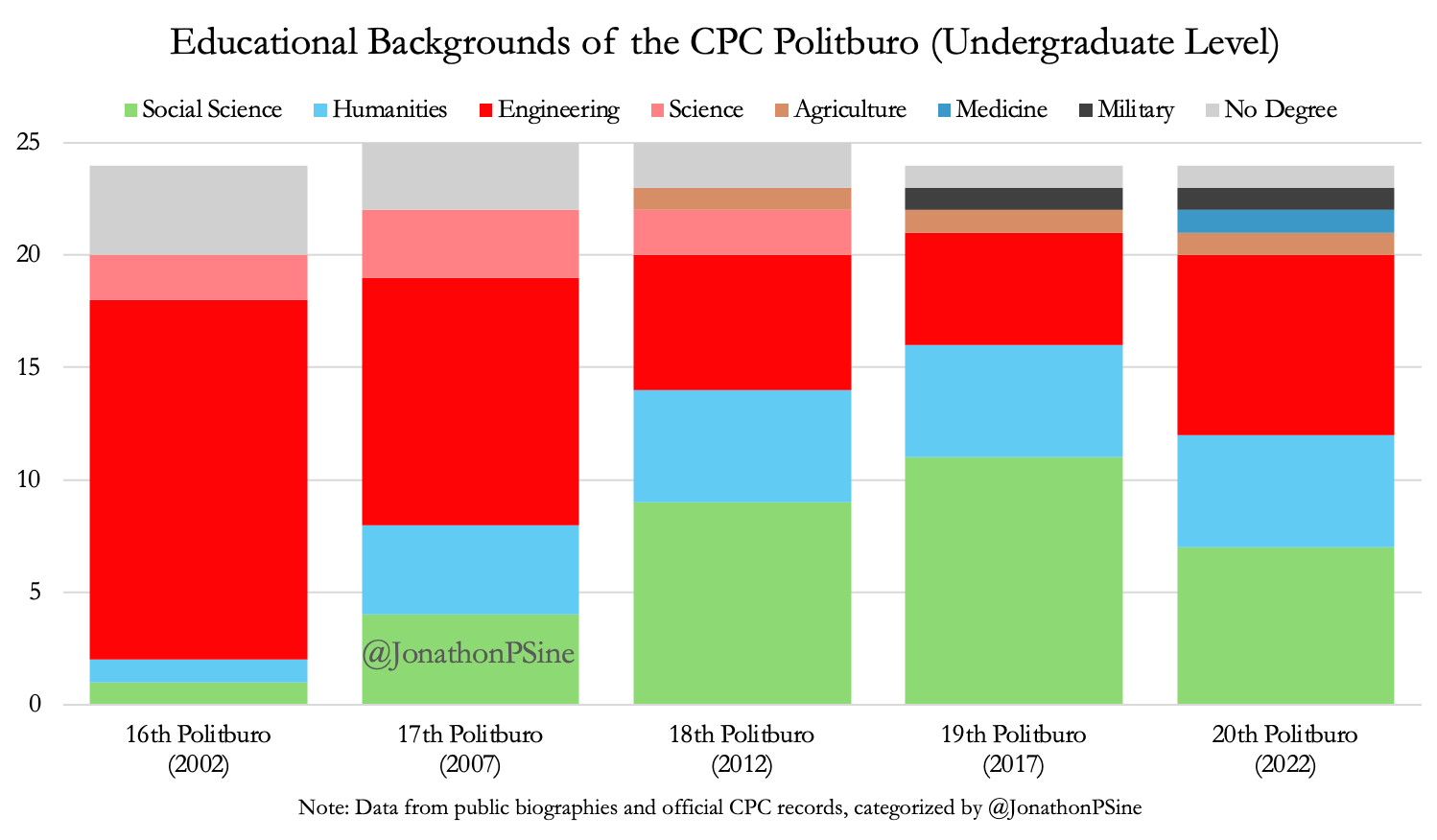

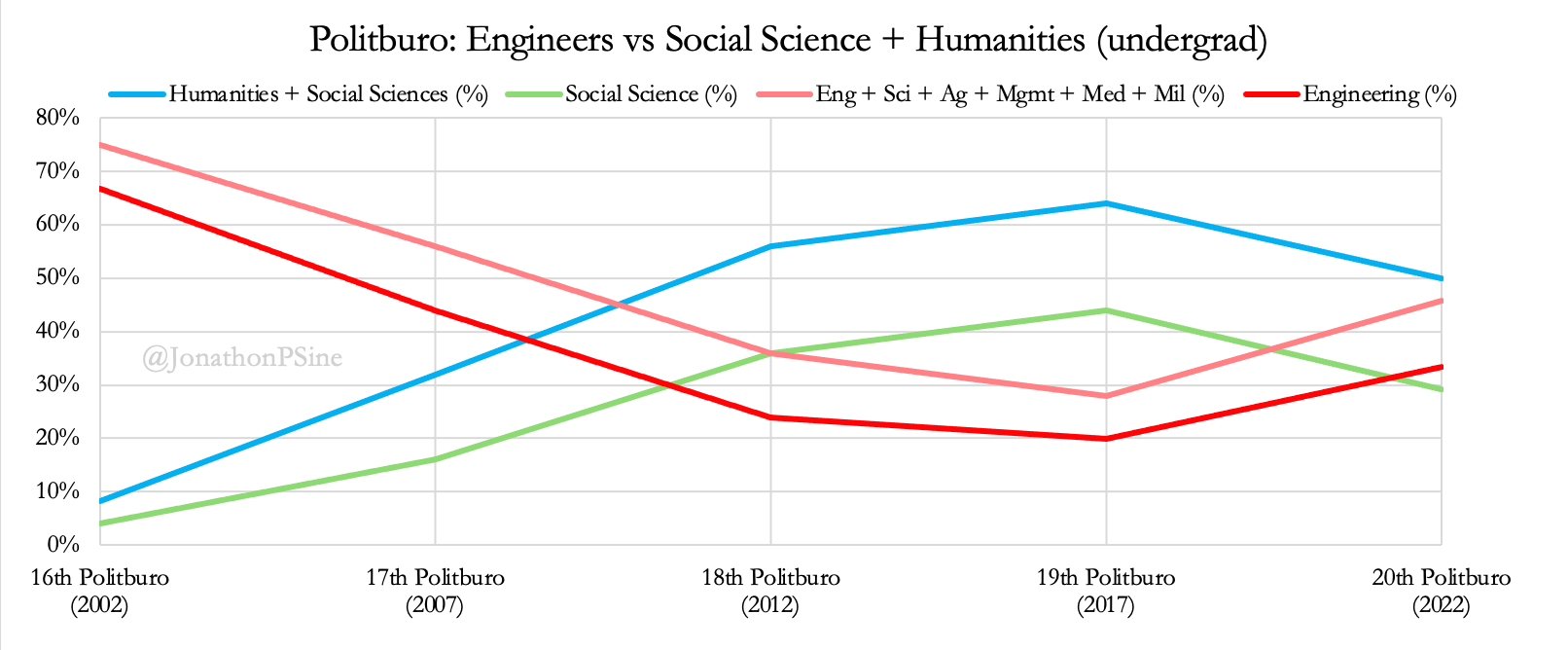

Breakneck also makes a big to-do about the supposedly engineering dominated Politburo and its Standing Committee (PBSC). It notes, for example, that under Jiang Zemin—an electrical engineer by background—the entire PBSC was filled with engineers. The book also points out, accurately, that Hu Jintao was a hydraulic engineer specializing in water management, while Xi Jinping studied chemical engineering at Tsinghua. Unmentioned, however, is the ironic fact that Xi’s PhD, attained in-field, is actually a doctorate in law (in Marxist theory and political thought education).

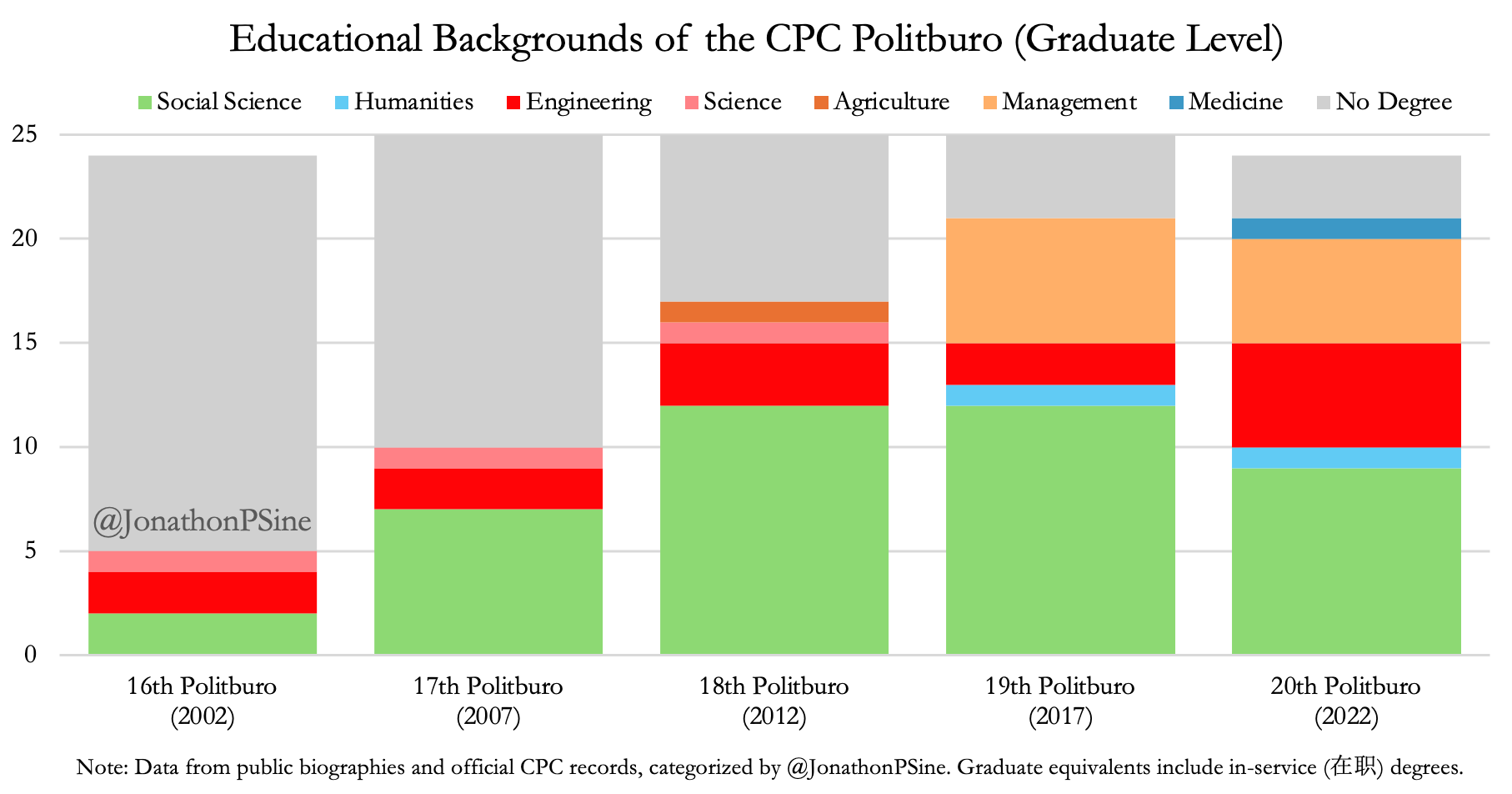

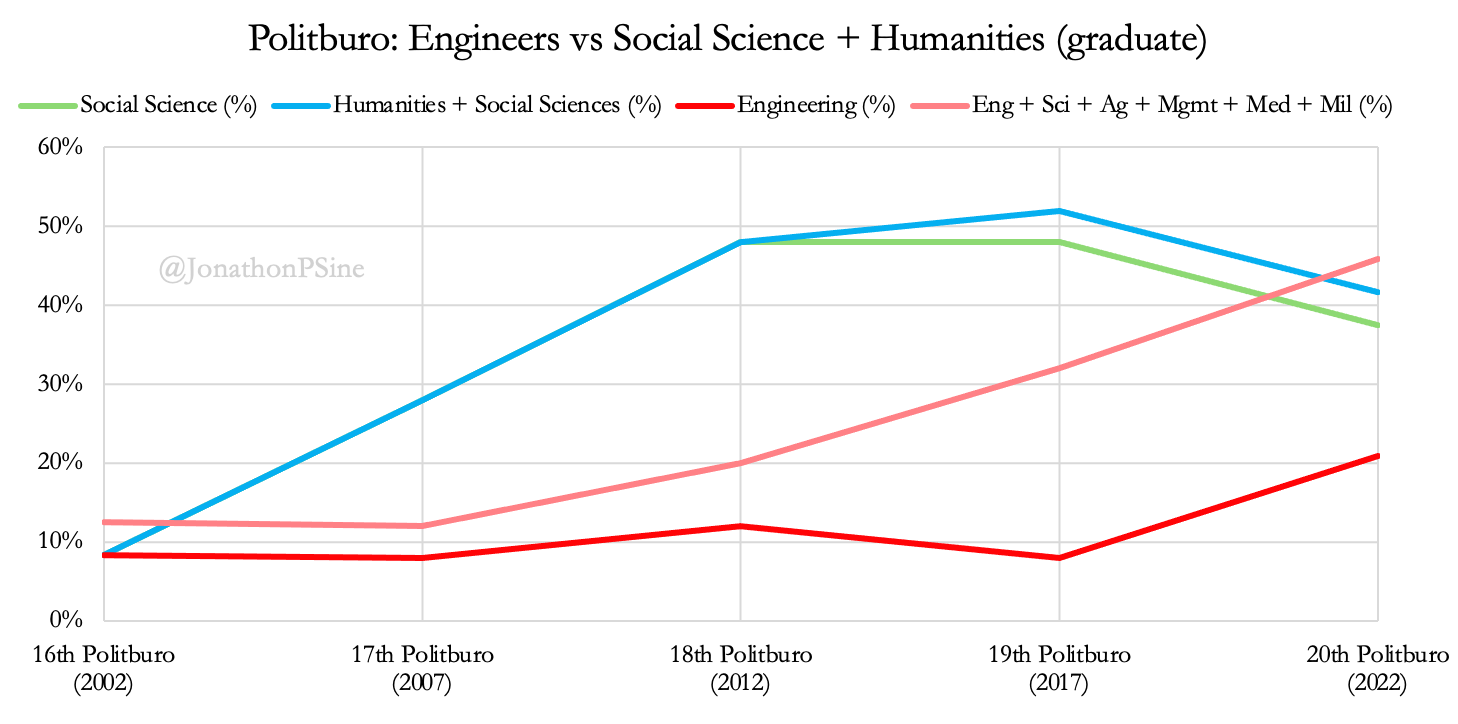

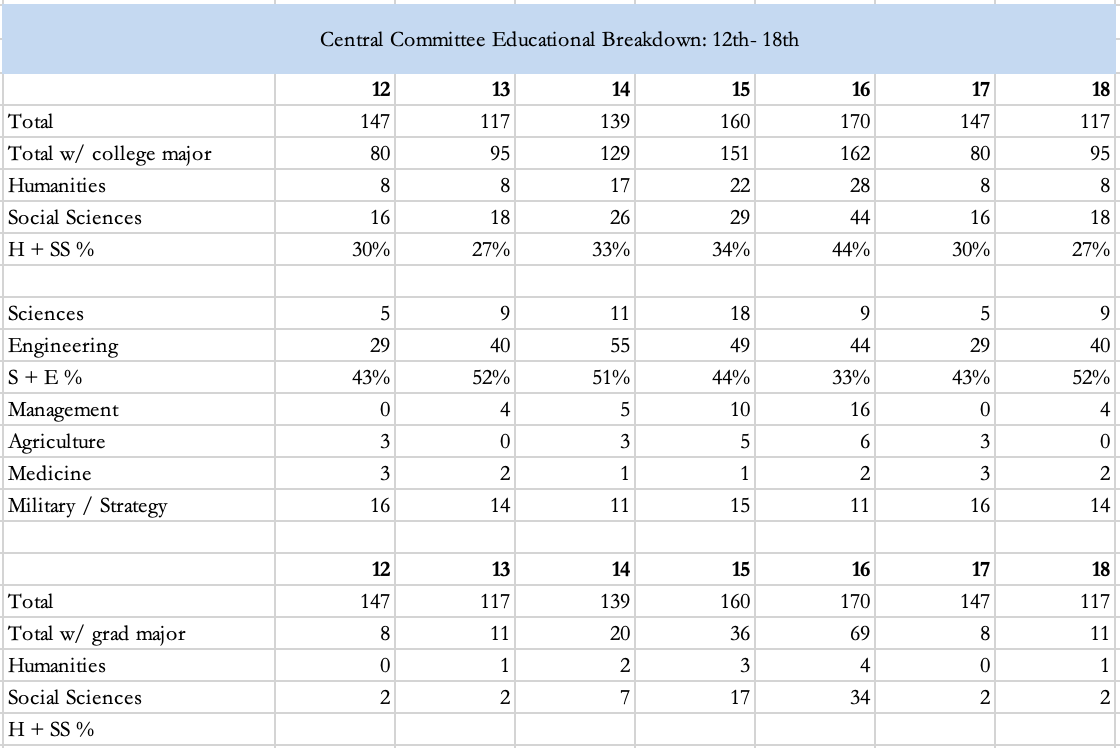

When you look at the data the story is not so neat. I compiled the educational backgrounds of China’s Politburo members from 2002 to the present. In 2002, a stunning 70% of Politburo members had undergraduate engineering degrees. But by 2017 the share had fallen to just 20%, before rising again to 33% in 2022. The book does not observe or point out this rise and fall. Instead, it skips any mention of this quite drastic fall and jumps immediately to pointing out the rise of an ostensible aerospace engineering clique at the 20th Central Committee.

The graduate-level training Politburo members have received, meanwhile, shows a long-standing tilt toward social science and managerialism. Most of this education comes via the Party school system. Fieldwork at lower levels, mostly done under Hu Jintao, confirms this system wide focus on management, social science, and law (though there are also technocratic/engineering classes). Overall, graduate training for China’s elite leaders is mostly a balance of ideology instilling “Leninist party discipline” with education on becoming “modern, competent managers of increasingly complex organizations.”22

For the sake of completeness I wanted to extend the analysis to the entire Central Committee. But data completeness issues stopped me. Still, from the 12th Central Committee (1982) up to the 16th (2002), we do see a similar trend of increasing pluralization in educational backgrounds (there does seem to be a shift back toward engineering in the less comprehensive data thereafter).23

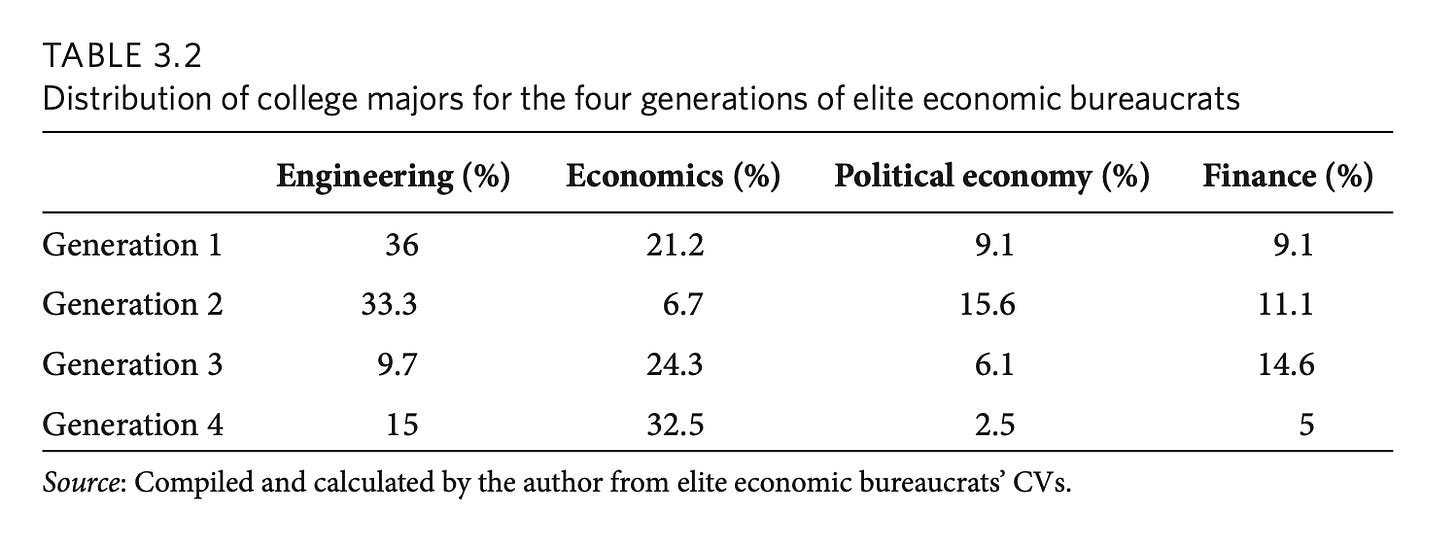

There is a broader story here as well of increasing managerial specialization across the bureaucracy. The education background of China’s elite economic bureaucrats, for example, was once engineering dominated, but now reflects more specialization in economics. (MIIT, the main industrial policy organ, is dominated by engineers, befitting its role).

Overall the picture that comes into focus—particularly at China’s apex—is a Party-state more professional-managerial than strictly engineering. Perhaps pedantic, but “managerial elite,” “managerial class” a-la James Burnham, or technocracy, or John Kenneth Galbraith’s “technostructure,” etc could all be more comprehensive.24

The Engineering State — and Its Limits

Breakneck’s first two chapters, following the introduction of the “big idea,” focus on building infrastructure—“Building Big”— and China’s manufacturing and tech ecosystem—”Tech Power”. Guizhou and Shenzhen the respective stars of the show.25

Building Big ultimately culminates in a didactic point: “China has shown that financial constraints are less binding than they are cracked up to be… China’s policymakers have declined to be bound by some of the fundamental tenets of Wall Street investors—reduce investment, shrink assets, produce profitability…Perhaps it will trigger financial distress in the future. So far, however, building big has improved the lives of regular people, not just a narrow set of elites” (p. 54-55).

Meanwhile, the chapter on Shenzhen becomes a paean to manufacturing, to the world of atoms over bits, to “physical and industrial technologies over virtual ones like social media or e-commerce platforms,” and to the communities of engineering practice enabled by a thriving manufacturing ecosystem (p. 59).26

The book wants to argue that America must care more about its industrial structure, its industrial base, and its technical talent pool. These are characterized, in large measure, by communities and networks of engineering and technical expertise laden with tacit knowledge—what James C. Scott would have called mētis, or what Willy Shih and Gary Pisano described as the “industrial commons.” These intangibles are real, and they can disappear to the detriment of the broader economy and innovation ecosystem.27 Knock-on innovations follow from seemingly “traditional industries,” such as production of LCD displays, and as Intel’s CEO Andy Grove similarly argued in 2010, by offshoring so much so fast America “broke the chain of experience.”

“American manufactures spent the better part of three decades unwinding its stock of process knowledge when it opened so many factories in China. Every US factory closure represents a likely permanent loss of production skill and knowledge. Line workers, machinists, and product designers are thrown out of work; then their suppliers and technical advisers struggle as well. Entire American communities of engineering practice have dissolved, leaving behind a region known as the Rust belt. But they were continuously scorned by economists and executives, who sought low-wage production in the name of globalization. Still today, many American economists doubt there is anything special about manufacturing and put their faith in the inevitable march to a service economy.” (p. 78).28

Why, Wang asks, has the American manufacturing base “rusted from top to bottom? Why have so many manufacturers crumbled?” Part of the reason, he suggests, is “financialization.” Namely, “the culture of financial investors. Wall Street has been far keener to invest in capital-light businesses.” But most importantly: “the problem lies with American policy-makers and executives who fail to grasp the importance of process knowledge” (p. 77-78). The way forward, Wang argues, is this:

"The United States must regain, at a minimum, the manufacturing capacity to scale up production that emerges from its own industrial labs. If it does not, continuing to value scientific breakthroughs rather than mass manufacturing, then it might lose whole industries once more—as it did by inventing the solar photovoltaic panel but relying on China to produce them. The United States likes to celebrate the light-bulb moment of genius innovators. But there is, I submit, more glory in having big firms making a product rather than a science lab claiming its invention. Otherwise, US scientists would once again build a ladder toward technological leadership only to have Chinese firms climb it” (p. 92).

I am on board. But I wonder: will these chapters end up as sermons for an Abundance-pilled choir? For a steel-manned counter argument to the most common objections, one would have to look elsewhere.29 Breakneck probably does not help its case when witticism veers into bombast. At one point, for example, the book declares that the “departure of manufacturing has created economic and political ruination for the United States. We are still only beginning to understand how much it set the country back technologically” (p. 76).30 Given that the cases are prosecuted more by vibes than rigor, such a declarative statement rings hollow. The entire book has only 232 endnotes and suffers from a paucity of data. I appreciate that this is a “big think” kind of book, and I largely nodded in agreement while reading these sections, but here as in other places more data would have been helpful.

Re-Engineering The Big Idea

But my bigger qualm remains whether “engineering state” is the best label for China, and the book’s two chapters on social engineering—the one-child policy and Zero Covid—brought it to a head.

Breakneck recounts the story of Song Jian, a cybernetician specialized in missile control systems, and his influence in pushing China over the monstrous “social engineering” edge of strict population control (a story retold largely via recourse to Susan Greenhalgh’s research).31 Alongside Qian Xuesen, Song is China’s most famous scientist. Wang analogizes Song’s influence in China to Albert Einstein’s in America. Most are familiar with the story in broad-strokes. I will not attempt to recapitulate the story’s details here (it was my unexpected favorite in the book, and people should read it themselves).

The most nihilism-inducing part of the entire saga is that China’s fertility rate, like most of the world and particularly East Asia, was already rapidly declining. Over 300 million abortions and 130 million sterilizations were forced down people’s throats—inflicting often unspeakable trauma across an entire generation of people—with practically no impact on the trajectory. It is ironic that this was the first major policy initiative of the allegedly more “pragmatic” post-Mao leaders, almost all of whom, from Deng on down, pushed for it with enthusiasm.

But was this a story of the engineering state? Or, as Greenhalgh would have it, of scientism?32 Is there a distinction worth pursuing here? What about James C. Scott and his “high-modernist” terminology, which fits this case precisely?33 Does “engineering state” effectively convey how and why China pursued the one-child policy? America was filled with Paul Ehrlichs and eugenicists, and for a time got away with implementing atrocious sterilization campaigns, if never at China’s scale.34 Breakneck states that “Chinese leaders were just enough exposed to the West to absorb [their] neo-Malthusian doomerism, without being exposed enough to the Western pushback against it” (p. 118).

Yet the most fundamental enabler of this policy was not that the idea found a receptive audience of high-modernists, but rather that it found them in a state unconstrained by checks on power. Indeed, the theory and organizational practice of politics at the core of China’s Party-state—Leninism—glorifies rejection of “bourgeois constraints” on executive power, leaving the Leviathan of the so-called people’s dictatorship unencumbered to do as it will. Much as German idealism achieved full odious bloom in places lacking and/or rejecting constraints on the state, so too did Western neo-Malthusian doomerism.

Breakneck’s subsequent chapter applies the “engineering state” frame to Zero-COVID less convincingly. It is a strange engineering mindset that would deliver the single-minded, often whacky, all-of-society mobilization that lasted so long past its expiration date. Shouldn’t an “engineering state” have prioritized the more obvious technocratic solution of forcibly vaccinating everyone, particularly the elderly?

The issue at bottom is of course more political. It all went awry not because of an engineering mindset, but because of the excesses of campaign-style mobilization centered around all too simple goals. A pattern that recurs regularly in unconstrained Leninist systems. In fact, a little bit more technocratic engineering around vaccine uptake among the elderly would have been helpful.35

Beyond Engineering: The Leninist Developmental State

I prefer the term Leninist developmental state (with Chinese characteristics). Both “Leninist” and “developmental” are freighted words: they convey the drive to transform not only the material world but also the social, moral, and psychological world of man. Leninist also signals a prescribed organizational form for carrying out this project. It proscribes rival centers of power or organizational centers that might intermediate between the Party and the citizenry or otherwise mobilize them. That is why the Party leads all, why every major state organ, every large company, and any influential organization is shadowed by a Party committee.

“Engineering state” hints at, but does not quite encapsulate, the totality of the Party-state’s transformation imperative. Anyone who has walked through China and seen the ubiquitous, sometimes comical, exhortations to behave in a more “civilized” fashion will recognize a bit of the impulse. Stalin’s line about writers as “engineers of the human soul” captures part of it, but only obliquely. A more fitting label should speak to the comprehensive project of material, psychological, and spiritual cultivation at play: an amalgam of Confucian moralism, Marxist-Leninist theorizing, and high-modernist ambition, all harnessed toward scaling the contemporary heights of wealth and power. These are captivations that stretch back decades, centuries, if not in some ways millennia. Xi Jinping’s emphasis on “spiritual civilization” is merely the latest manifestation.

The Party-state’s modus operandi often veers into crude political mobilization rather than anything resembling technocratic engineering. This reflects the persistent, irresolvable tension between red and expert. While Xi Jinping is more Liuist than Maoist—favoring bureaucrats, technocrats, and specialists—the tension endures. Elizabeth Perry has traced the same dynamic in her studies of “managed” campaigns and work teams: Mao-era governance retooled in a more professionalized, controlled manner.36 This is also visible in Mao and Xi’s respective answers to the big question: how can China “escape the dynastic cycle of rise and fall?” Mao’s first answer: popular supervision of the state. Xi’s second: a controlled, professionalized, one might even say bureaucratized, “self-revolution” of the Party-state.

China’s rapid growth, meanwhile, has been as much about the Leninist system re-tooling itself to be market compatible as it has been about an engineering state building infrastructure. A developmentalist impulse was propagated from on high and penetrated all levels of the Party-state. Officials, even those with no obvious economic function, raced to meet breakneck growth targets, often enriching themselves in the process. In this sense, China’s developmental state diverged from the smaller East Asian cases: it bore “Chinese characteristics,” defined less by a singularly competent central bureaucracy than by a broad, productionist ethos replicated at national, provincial, and local levels.

Over time, however, the Party-state has become more professionalized and technocratic, drawing not only on engineers but also on a growing cadre of managers, economists, and other experts. The NDRC, for example, was consolidated in 2003 and MIIT in 2008 (the latter perhaps China’s closest equivalents to Japan’s MITI). Concepts like “managerial elite,” “technostructure,” or Wang Yingyao’s Markets with Bureaucratic Characteristics illuminate facets of this system, but like “engineering state,” they remain incomplete.

Leninist developmental state speaks to the immutable tension, despite a shared aspiration for development, between reds and experts. It also does not occlude the very real engineering imperative that one can see stretching from the dynastic era to the present. But most importantly: it captures the organizational imperative at the heart of China’s Party-state.

There is something else: over the last few years, China’s most breakneck construction era—a defining feature of Wang’s engineering state—has already begun receding into the past. One of the most profound symbols, China’s private property developers have, like Wushan’s old county seat, largely vanished.

Beyond Breakneck?

Over the past four decades, China has accomplished an infrastructure and industrial buildout that took the United States nearly a century, from 1870 to 1960. Steel, cement, railways, highways, ports, power generation—the entire built environment has been remade at a pace and scale the world has never seen. In effect, China speed-ran the Second Industrial Revolution. Its youth—like those I met in Wushan—are unabashedly enthusiastic about the world of atoms, as the country’s education system and political structure heavily orient toward building, sustaining, and managing a techno-industrial society.

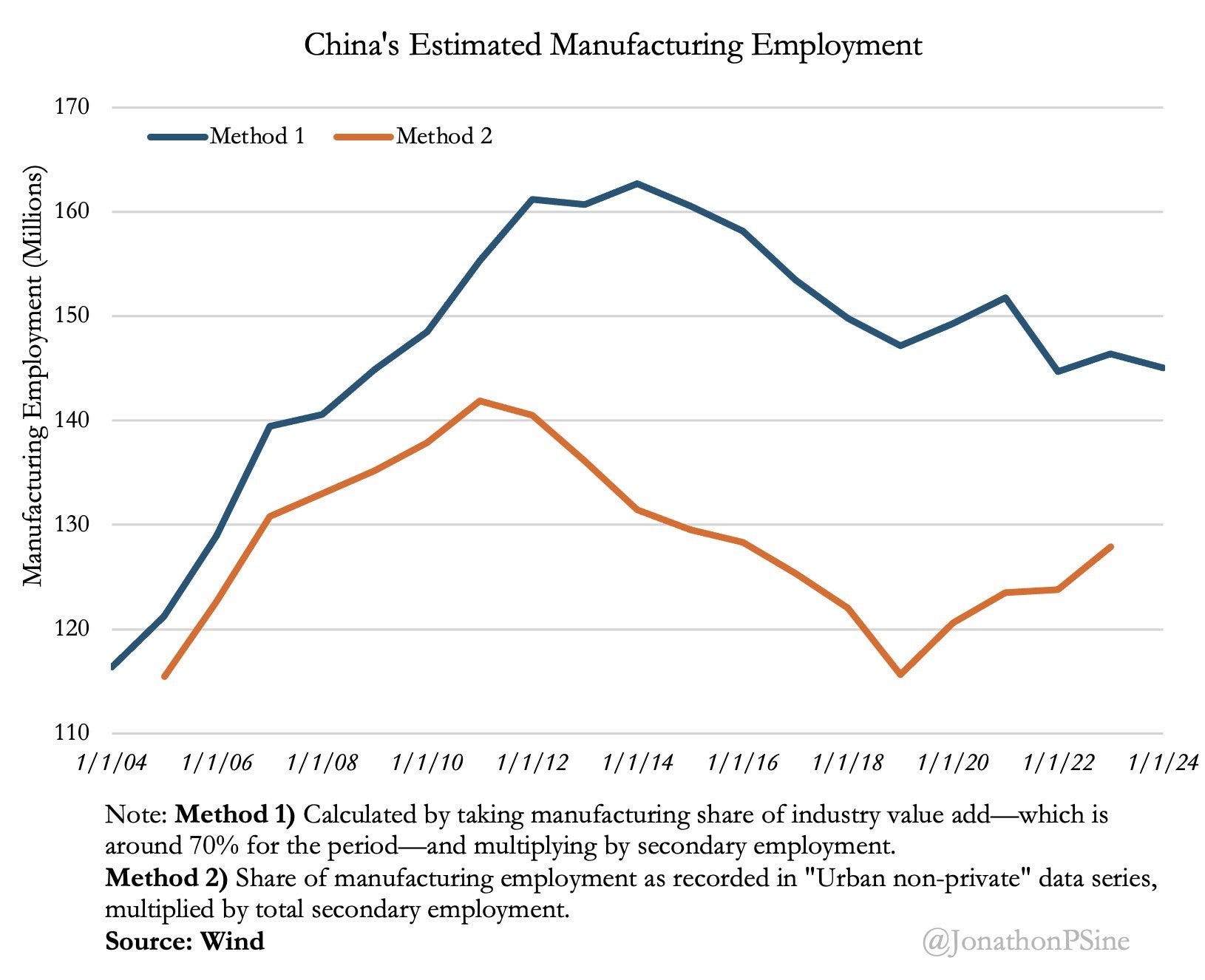

Yet the labels “breakneck” and “engineering state” fit less neatly today than they did in the 1980s through the 2010s. The diversification of Politburo members’ educational backgrounds hints at this shift, but the deeper reason is that China has passed an inflection point in investment and manufacturing growth. Even the 14th Five-Year Plan’s modest pledge to keep manufacturing’s share of GDP “basically stable” requires an almost herculean push against the historical tide. China had already lost the equivalent of America’s entire manufacturing labor force in a decade, prior to stabilizing or increasing (depending on measurement method) around the time of the 14th FYP.

This is not an argument that China has “over-invested.” It is a recognition of a near-universal pattern: as countries climb beyond middle income, their industrial and manufacturing share of GDP shrinks. China’s global industrial and manufacturing shares—astonishing at more than 30 percent—are peaking.

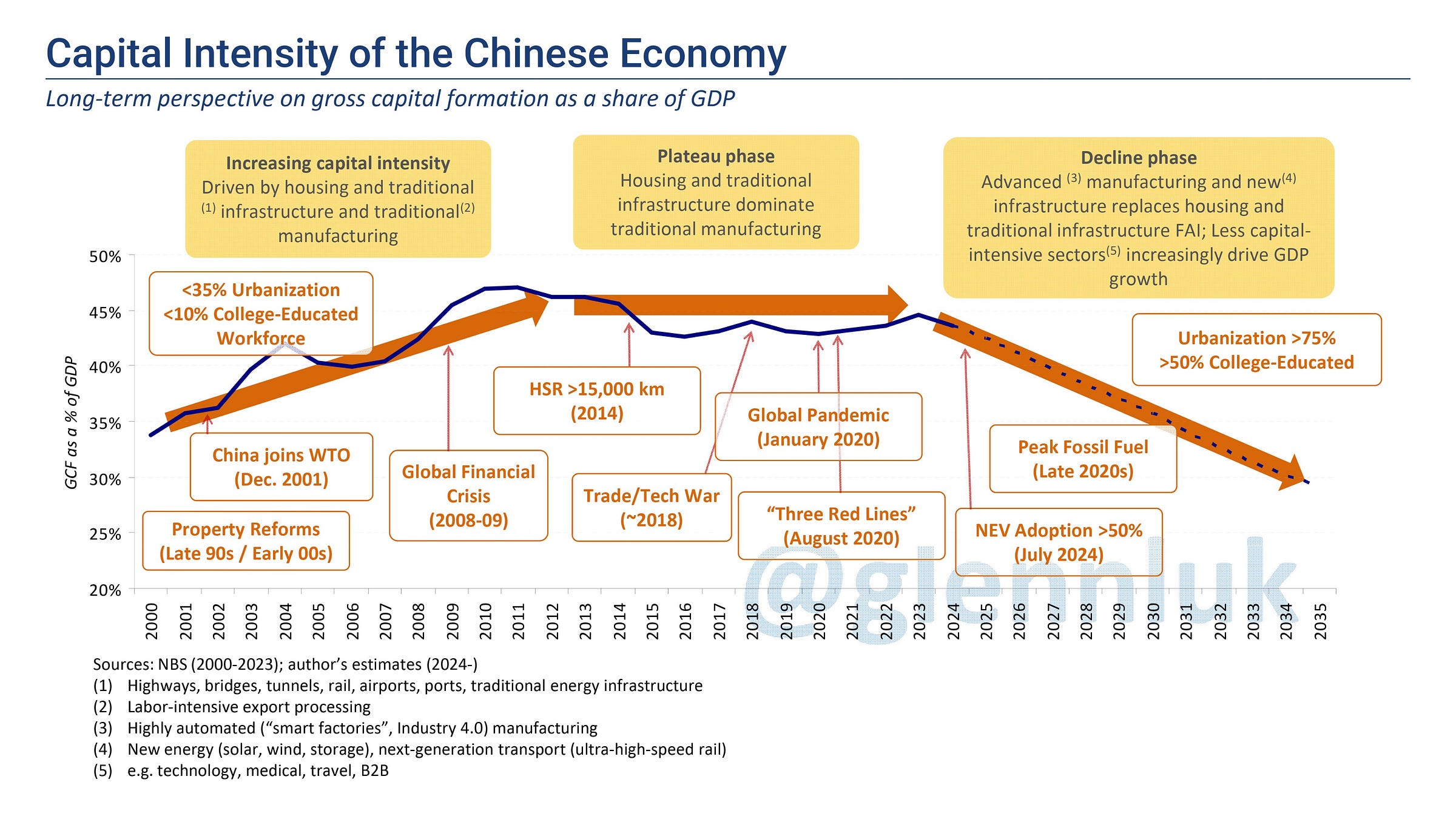

As I wrote, they are unlikely to come anywhere near the 45 percent nonsensically projected by UNIDO (a forecast Wang and others have repeated with insufficient skepticism). China’s capital intensity, as Glenn Luk has depicted, is entering an inevitable phase of decline.

Just as the U.S. hit a plateau in physical buildout in the mid-20th century, as China closes on completing its speed-run through the second industrial revolution, its priorities are shifting. Since Hu Jintao, and especially under Xi Jinping, the Party-state has moved from single-minded industrial blitz to a proliferating set of mobilization goals: environmental cleanup, tech self-reliance, rural revitalization, etc. This is even visible in the new CPC history museum exhibits on these leaders!

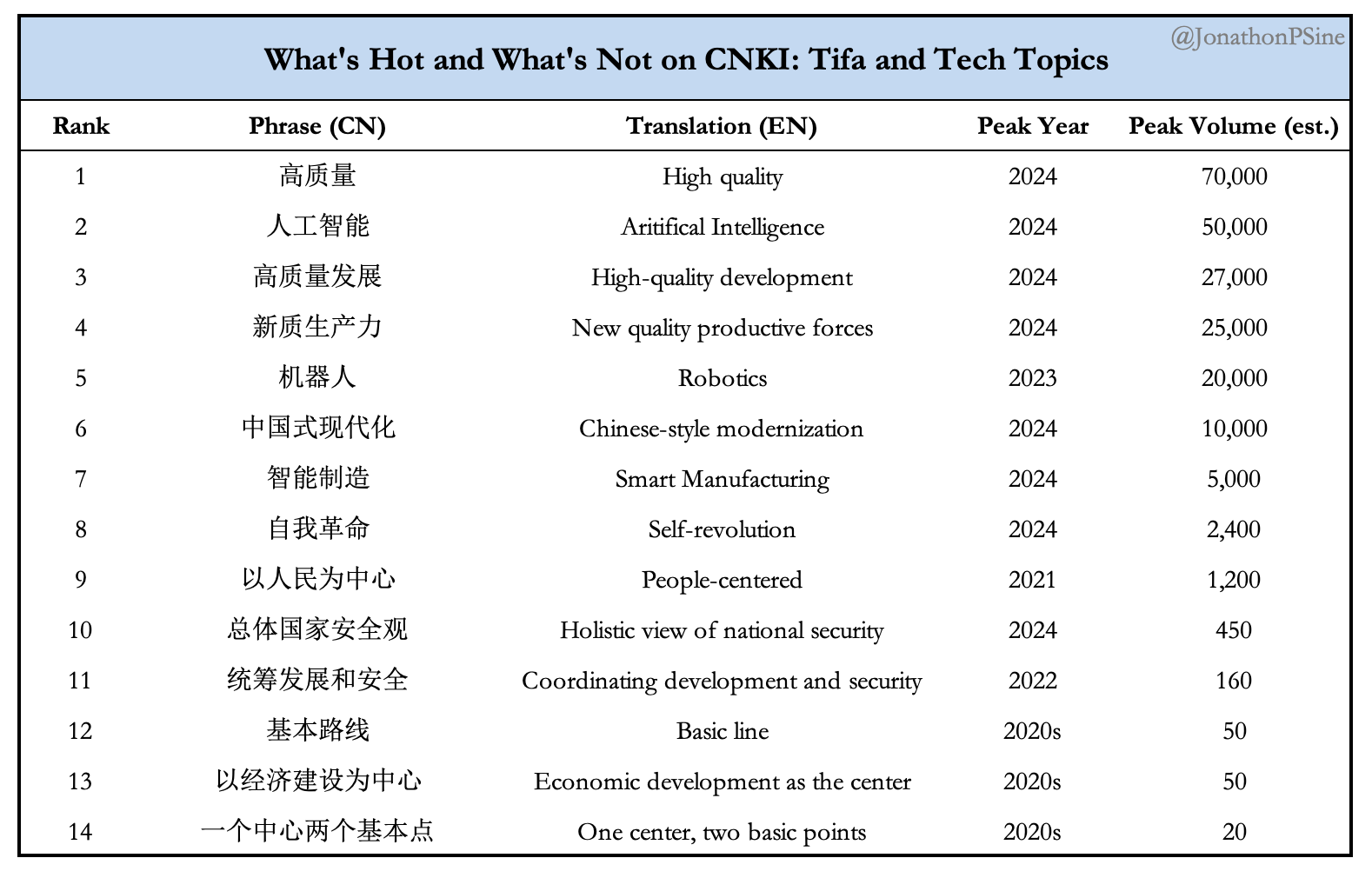

Today is the era of so-called “high-quality” development. Very strangely this does not get a single mention in Breakneck, despite the fact that it is not only Xi’s most frequently harped on economic policy tifa (提法) but also the singular hottest topic on China’s research agenda (per CNKI)—even surpassing artificial intelligence:

In 2025, a fresh wave of anti-involution policies is rolling out, extending the lineage of Xi Jinping’s supply side structural reform campaigns all the way back to 2004 when Hu Jintao’s Premier Wen Jiabao first announced the “Four Uns.” GDP remains high priority, but cadre evaluation forms now track a far broader set of indicators. New organizations and ideologies steer China toward “Chinese-style modernization,” which however inchoate means moving beyond breakneck growth. “Engineering state” is, in many ways, already appearing timestamped. But so long as the Party retains its uncontested hold on power, Leninist developmental state will remain apt.

Et Tu, America? The Lawyerly Society

Although Breakneck is mostly focused on China, the big idea extends via comparison to America.

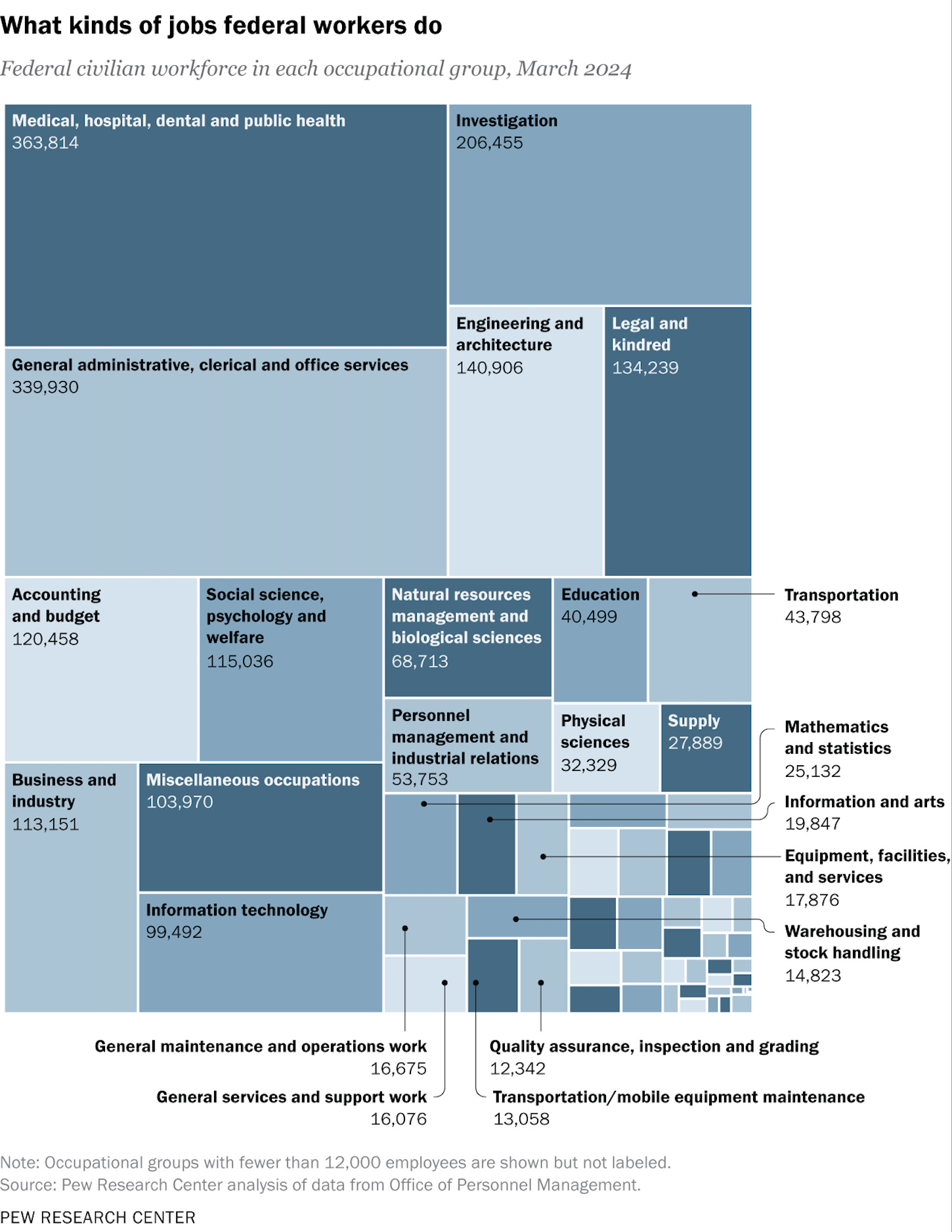

Ironically, whereas the data I assembled paints Chinese society as disproportionately engineering-oriented (as measured by educational background), it is the American state that is disproportionately lawyer dominated while the education background of society at large is varied. Perhaps we have an Engineering Society facing off against a Lawyerly State?

Below I re-group US college majors according to Chinese disciplines to allow for rough comparison. Surprisingly, the ratio of science/engineering to humanities/social sciences is 2:1, the same as in China (if one groups management with science/engineering, as I also do for China). There are more American undergraduates in STEM than one might expect from news headlines—or from reading Breakneck.

Meanwhile, I also re-group America’s 3.2 million graduate students into Chinese disciplines for comparability. In any one year, America has roughly 120,000 students enrolled J.D. degree programs (and ~20,000 other non J.D. programs). In other words, only 4% of American graduate students are enrolled in law. America thus has a roughly equivalent number of PhDs enrolled in engineering and physical sciences (not including masters) as it does in law schools.

(Note: This was a far heavier lift than the undergraduate data, as a result these estimates are ball-park! Unlike the undergrad data which at least had enrollment numbers for 2019-20, the U.S. graduate enrollment data is not well aggregated. To deal with this, I scaled up from single year graduation totals. See image caption for methodology overview. I also uploaded the spreadsheet to google so others can see specific choices/estimates. As is standard practice, MBAs are included within management under Masters enrollment, while MDs and JDs are included under medicine and law respectively within PhD enrollment.)

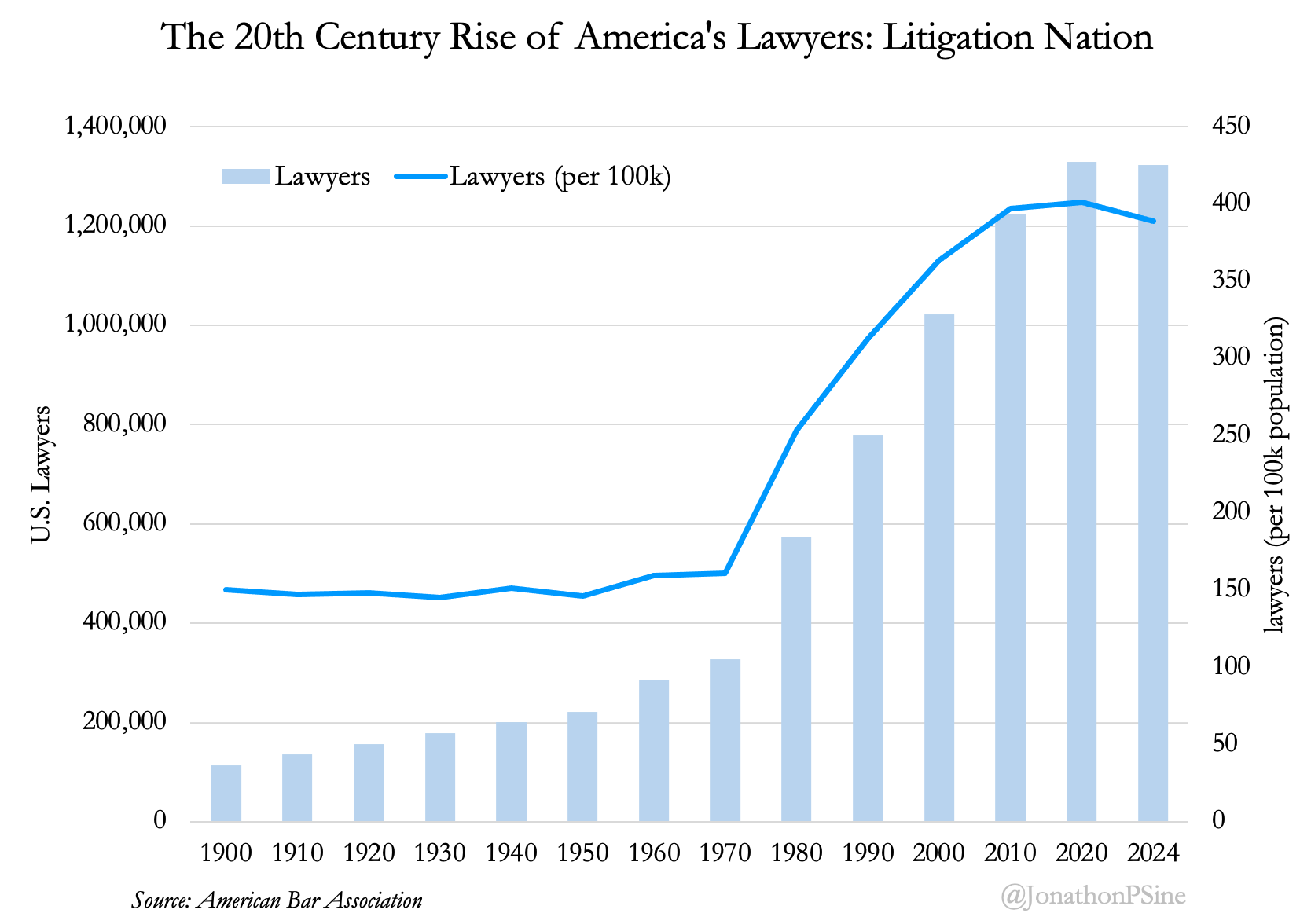

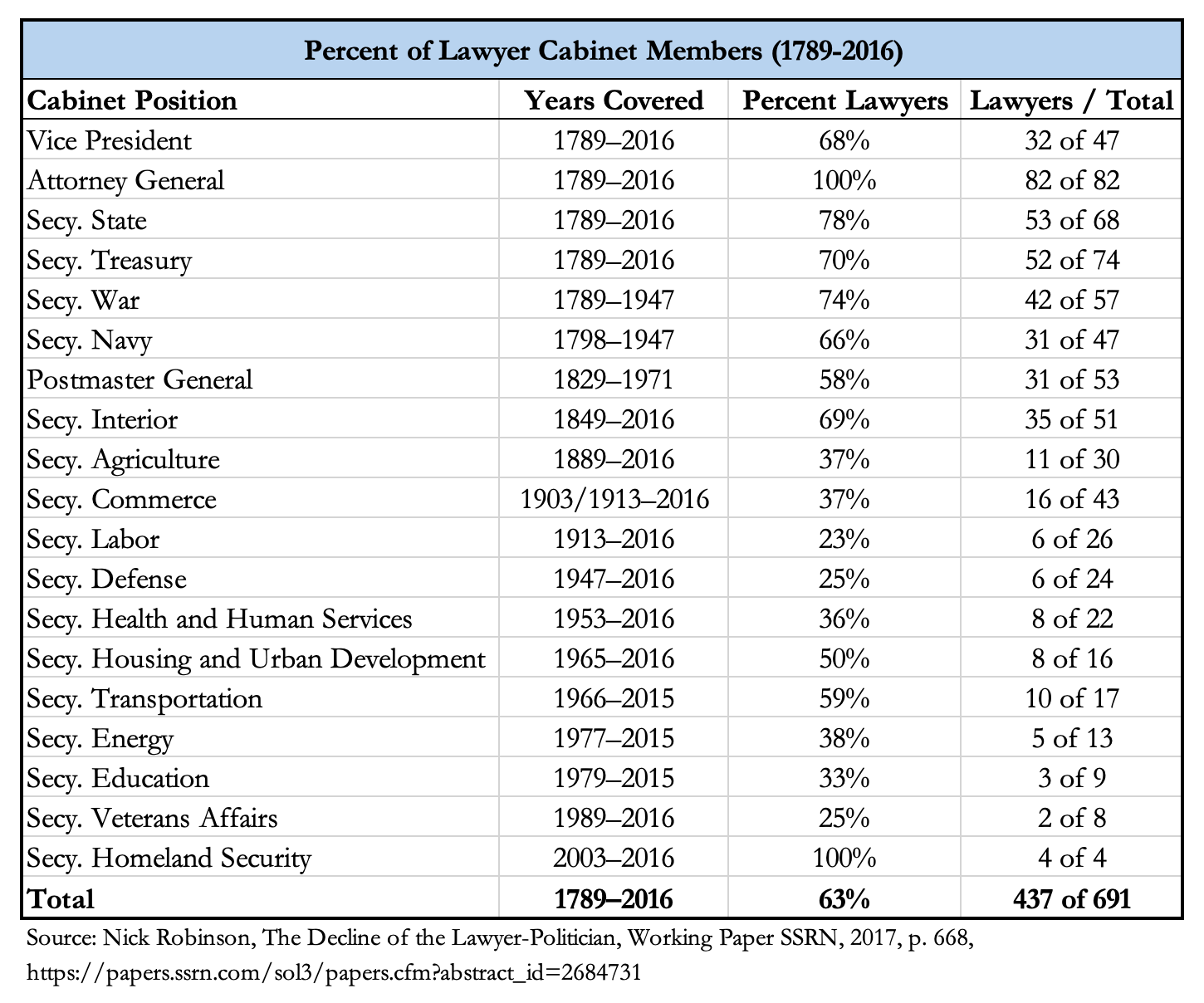

Whatever the case may be in education, lawyers have absolutely dominated the American state.

From the signing of the Constitution in 1789 to 2016, 63% of all Cabinet members have been lawyers. While I don’t have time series data, the disproportionate share likely still holds. And, as Wang points out in the book, "from 1984 to 2020, every single Democratic presidential and vice-presidential nominee went to law school” (p. 4). Only two Presidents, Jimmy Carter and Herbert Hoover (who lived in China for a time), ever worked as engineers. The United States, Wang writes, “has a government of the lawyers, by the lawyers, and for the lawyers.”

And yet, the United States used to build, perhaps even build like China. Then in the 1960s or 70s, we stopped:

The United States used to be, like China, an engineering state. But in the 1960s, the priorities of elite lawyers took a sharp turn. As Americans grew alarmed by the unpleasant by-products of growth—environmental destruction, excessive highway construction, corporate interests above public interests—the focus of lawyers turned to litigation and regulation. The mission became to stop as many things as possible. As the United States lost its enthusiasm for engineers, China embraced engineering in all its dimensions.” (p. 4-5).

The rise of America’s lawyers as a share of population jives well with the interpretation that the spread of lawyers may relate to the building / investment slowdown that started after the 1970s. Data from the American Bar Association show an astounding uptick in lawyers around that period—in absolute numbers and as a share of the population.

Breakneck is a bit more singular in pinning the blame on lawyers, but the diagnosis is fundamentally the same as several recent books, from Abundance to Why Nothing Works to Public Citizen. Breakneck joins this chorus. It was not only the rise in lawyer numbers, they posit, but more importantly a comprehensive shift in lawyerly focus in the 60s/70s toward oppositional litigation.

Certainly, something did alter America’s ability or desire to develop its material environment beginning around the 1970s.

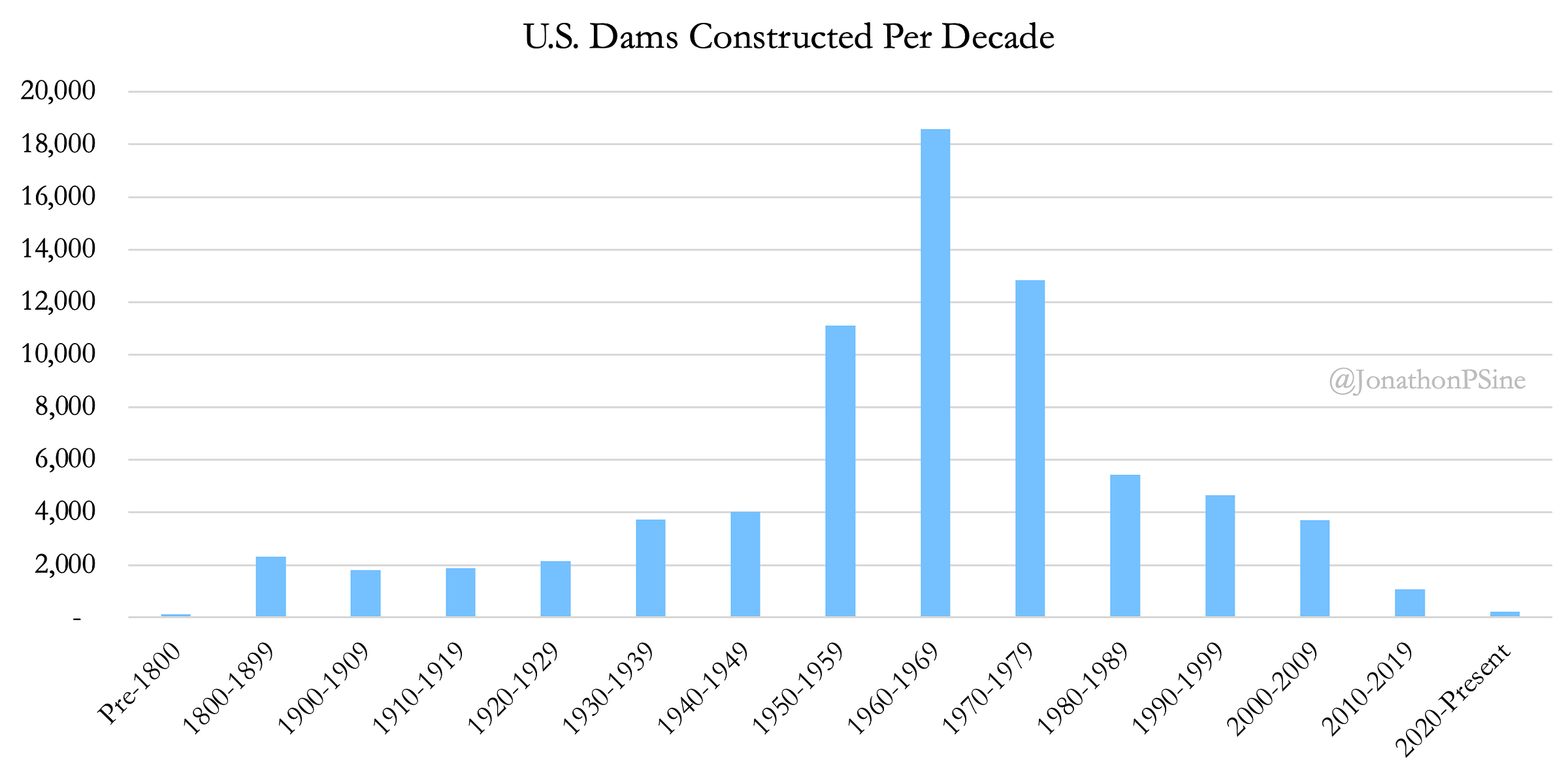

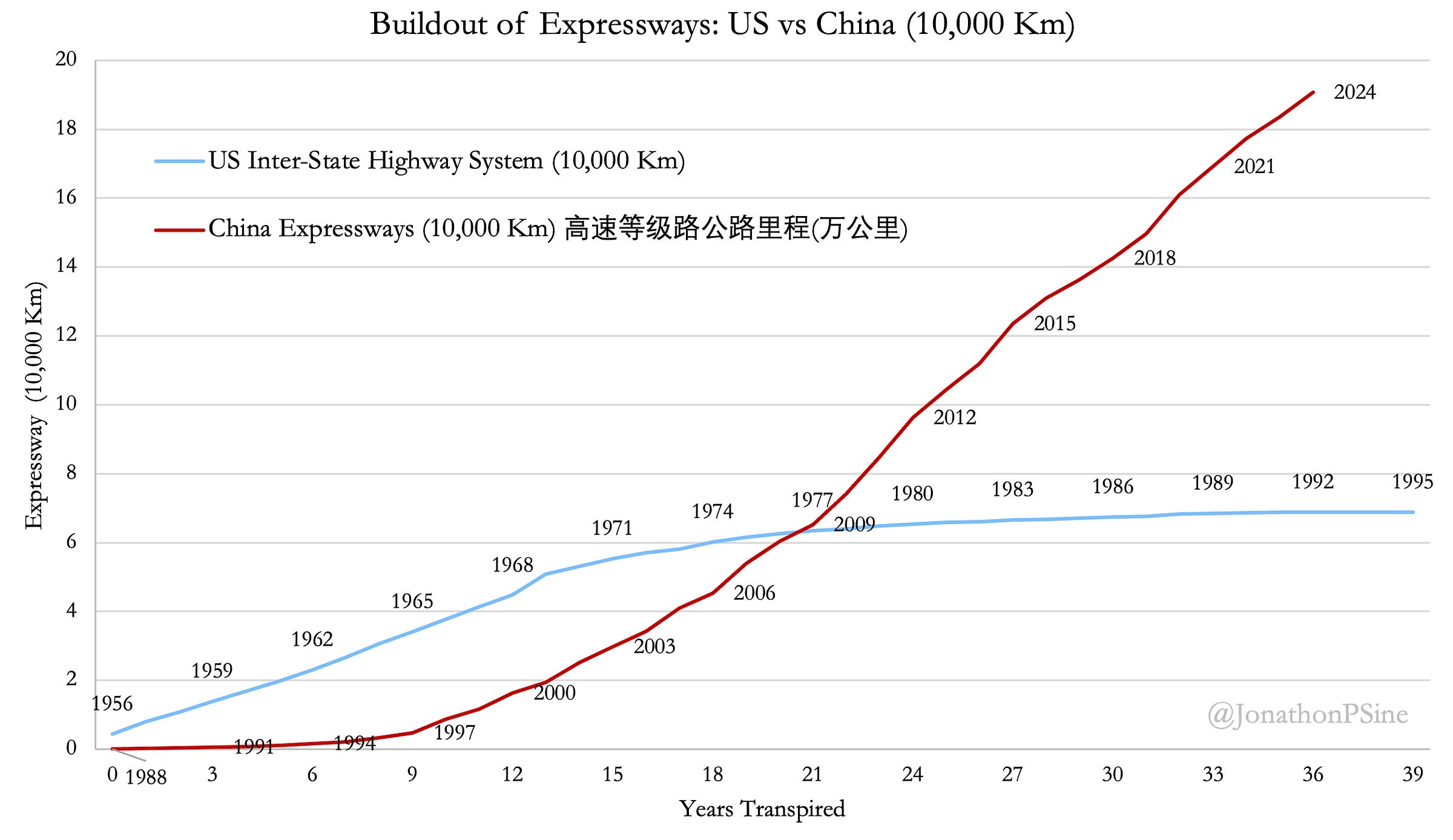

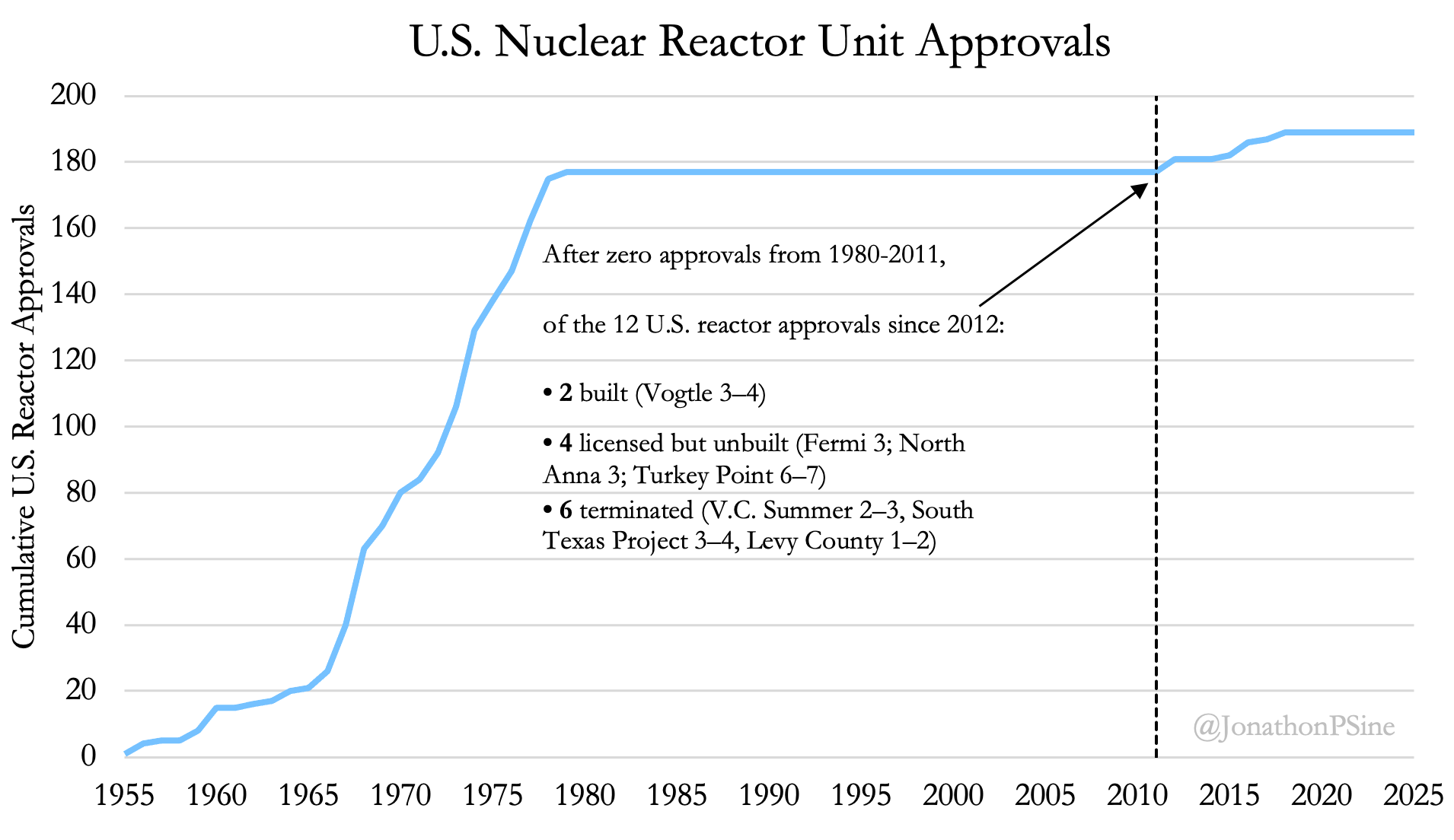

Consider America’s hydraulic construction (dams). Or America’s expressway buildout. Or nuclear facilities—where from 1955 to 1979 we went from 1 to 177 approved reactor units, and then approved not a single new one until 2011 (today, China is currently building 29 reactors, America zero). One can point to any number of indicators demonstrating the slowdown in the built environment.37

Breakneck is not shy about spelling out the results of this slowdown:

“Americans live today in the ruins of an industrial civilization, whose infrastructure is just barely maintained and rarely expanded” (p. 11).

“Americans are no longer able to appreciate that a physically dynamic landscape creates a sense of progress” [Which] “contributes to a blind spot that Americans have for China. People unable to appreciate the benefits of material improvements also don’t understand how it produces pride and satisfaction” (p. 33).

“What New York has lost since the 1960s are updates to its physical environment” (p. 223).

“What the United States has lost sight of is that the public might prefer a government that does something rather than one that’s so exquisite about process” (p. 228).

Anyone who has ridden Amtrak, taken New York subways, lived in the Bay Area or Los Angeles, or driven across the interstate highway system can sympathize.

Aside from pointing at lawyers, the book does not dwell much on the deeper causes.38

Where it does, the main target and focus is ideational, pointing the finger at an overzealous shift in societal priorities, engineered in large part by activists and authors. Robert Caro’s (1974) book the The Power Broker: The Rise and Fall of New York comes in for particular scrutiny (as it does in Why Nothing Works). Wang suggests that Caro’s book, along with Jane Jacob’s (1961) The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Rachel Carson’s (1962) Silent Spring and Ralph Nader’s (1965) Unsafe at Any Speed, were too successful in turning the tide of public opinion against Moses and his ilk. Wang writes: “the imperative that drove Moses—improving society through large-scale, government-led projects—had gone to the grave with him.” These books “taught Americans to fear and loathe engineers” (p. 220-1).39

While sympathetic to Breakneck’s argument, there are at least two big complicating factors.

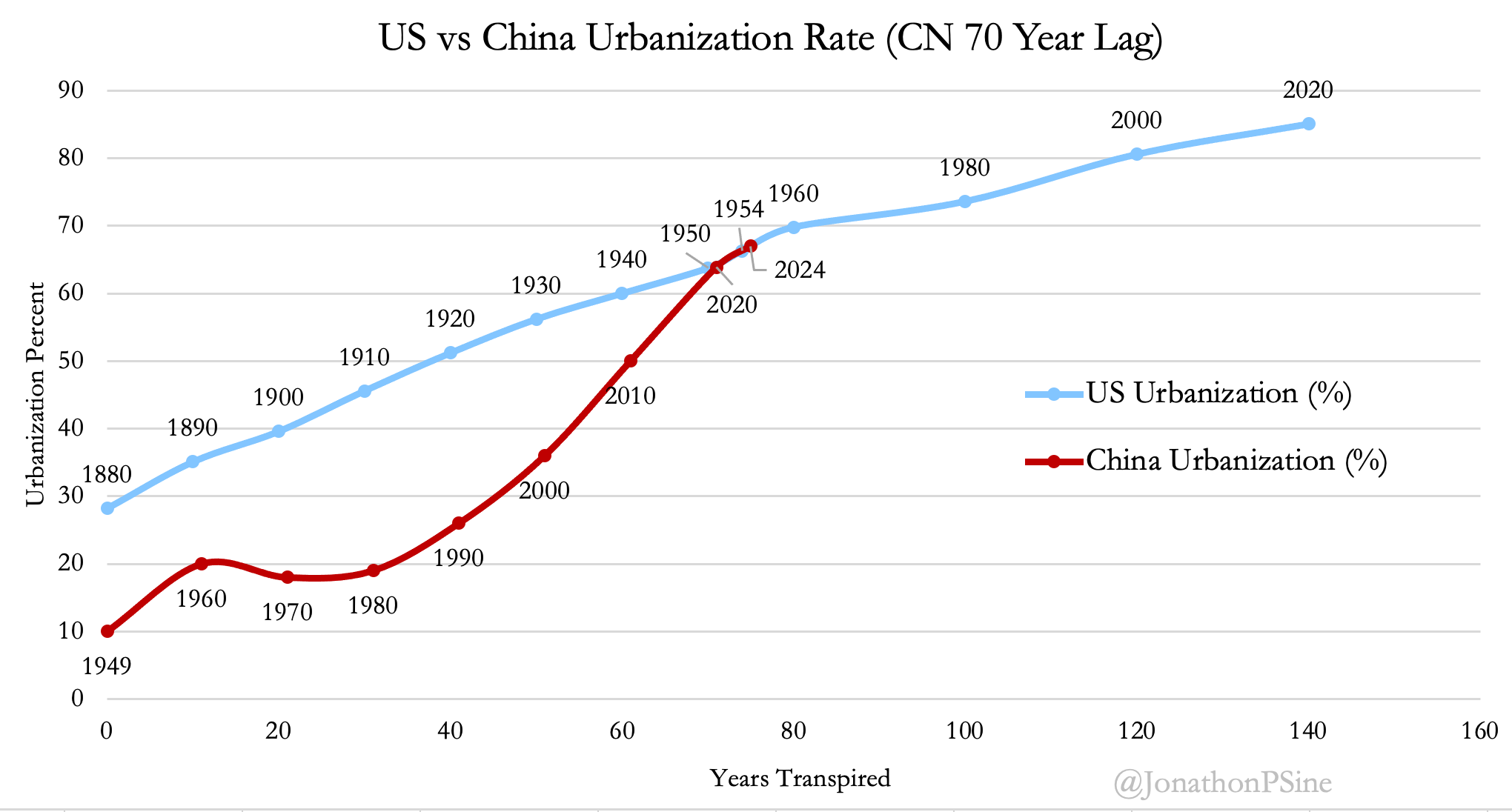

First, as with China today, America’s breakneck building phase was decidedly winding down by the 1960s. Urbanization went from 40% in 1900 to 70% by 1960, and grew much more incrementally over the next 60 years to 85% by 2020. The country simply did not need to continue building dams, expressways, and energy production facilities at breakneck pace. It became much more a matter of maintaining and upgrading (which has not gone well, at least according to the American Society of Civil Engineers’ report card). The story may be more about structural economic shifts than lawyers.

The second complicating factor is how much deeper this all runs.

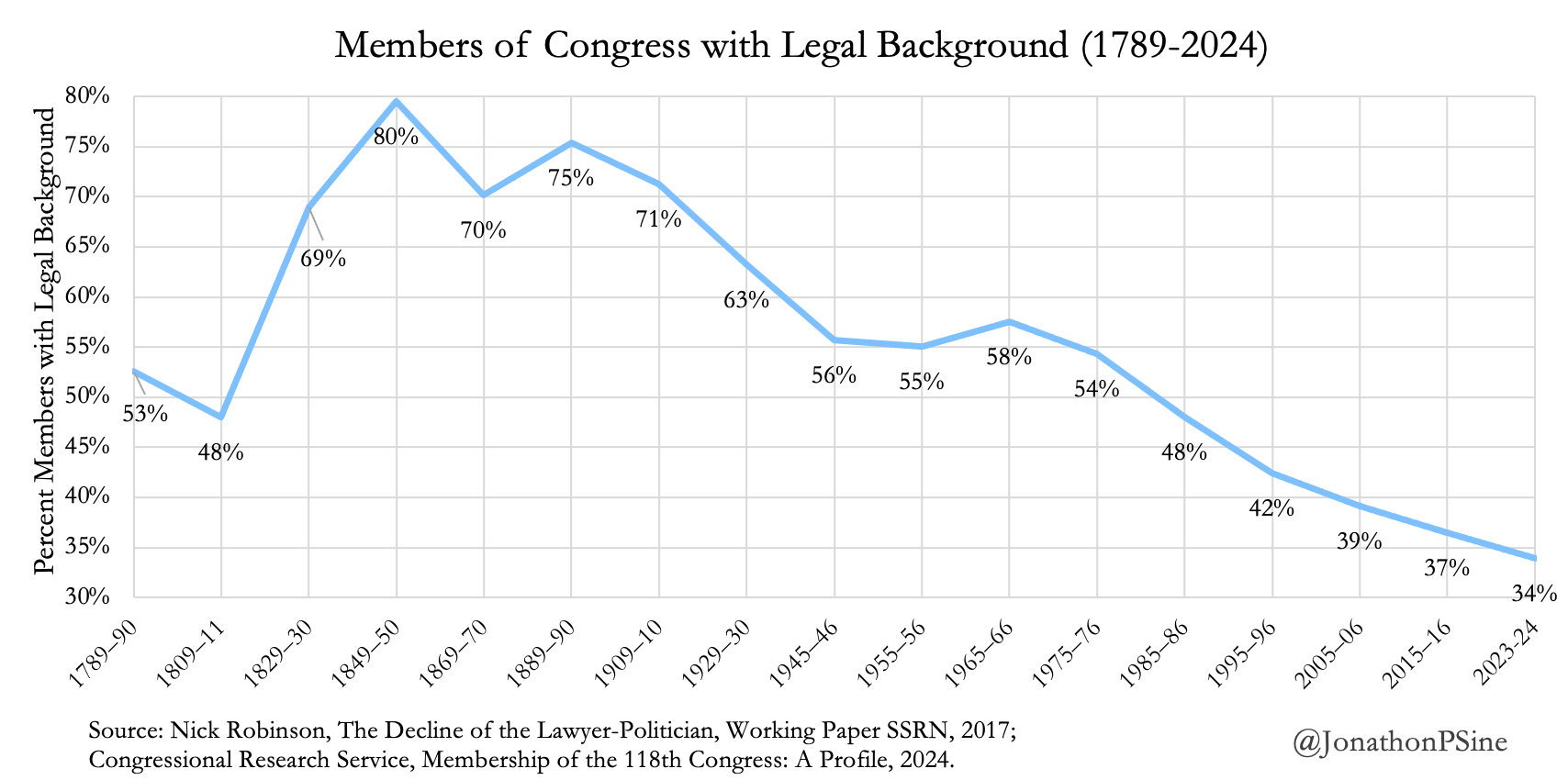

There was never a period in American government when lawyers did not dominate. If anything, lawyers may be less prevalent today in terms of background. Data on the composition of Congress, for example, is one hint. The Congressional share of lawyers has actually plunged to 34% over the last several decades (though it still has very few engineers: the Senate, the more lawyerly body, has 47 lawyers and 1 engineer). Meanwhile, the professionalization of the federal bureaucracy (which is not to say expansion—it has not expanded at all numerically since the 1960s) means executive agencies are probably staffed by a greater share of engineers, technocrats, and non-lawyer professional managerial personnel (though this is speculation).40

Overall, I think the proliferation of lawyerly proceduralism that Abundance, Why Nothing Works, Public Citizens, and now Breakneck all focus on is a major part of the answer. It is harder to think of a better term than “lawyerly society” to succinctly describe America. But one must keep in mind the 1960s/70s and the rise of litigation nation was part of a process, done in a uniquely American manner, of the country progressing beyond its own breakneck growth era.

Mandarin, Cadre, Lawyer, Bureaucrat

It can be hard to assess all of this without historical grounding. The most fundamental point is this: China has never, in thousands of years, known true constraints on the executive. China pioneered the world’s first centralized state, and with interruptions, has maintained a professionalized bureaucracy since the Qin dynasty in 221 BCE. China’s precocious state development could hardly differ more from America.41

America’s centralized state was born late and weak. For much of its short history, the United States barely had one. Only with the Civil War and its aftermath did a national administrative apparatus take shape—one that quickly receded, only to be rebuilt in fits and starts by a succession of statist presidents (Teddy, Wilson, FDR) largely under the pressures of the Spanish-American War, World War I, the Depression, and World War II.42 In its short two hundred some years, America has never known an unconstrained executive (despite what some conservatives may believe about FDR).

China today inherits the world’s most sophisticated dynastic bureaucratic tradition, layered with Soviet organizational templates, osmotically infused with East Asian developmentalism, and supplemented more recently by Western markets, capital, and FDI-linked technology transfer. The Chinese state may still suffer from fragmentation and all sorts of principal agent problems involved in administrating such a large territory, but is almost wholly unconstrained by alternative, organized centers of power and influence (i.e., intermediating organizations). The Chinese Party-state remains among the most autonomous executives in the world.43

America’s path to modernity, meanwhile, ran in the opposite direction. Before a centralized state or modern bureaucracy congealed in the 1860s, government rested almost entirely on judicial and legislative institutions. In nineteenth-century America, the courthouse was the citizen’s main point of contact with government. Contrast with China, where that role was filled by the county magistrate, creature of the imperial exam, serving at the emperor’s pleasure.44

“It is only a slight oversimplification,” Robert Kagan wrote in his opus on America’s system of adversarial legalism, “to say that in the United States, lawyers, legal rights, judges, and lawsuits became functional equivalents for the large central bureaucracies that dominate governance in the activist states of Western Europe,” to say nothing of China.45 America has been defined by legislation and the Constitution (Skocpol’s Bringing the State Back In) and ruled by courts and parties (Fukuyama, Origins of Political Order), hardly by a central bureaucracy.

This is backdrop for Tocqueville’s passage in Democracy in America:

If I were asked where I place the American aristocracy, I should reply without hesitation that it is not composed of the rich, who are united together by no common tie, but that it occupies the judicial bench and the bar. The more we reflect upon all that occurs in the United States the more shall we be persuaded that the lawyers as a body form the most powerful, if not the only, counterpoise to the democratic element. In that country we perceive how eminently the legal profession is qualified by its powers, and even by its defects, to neutralize the vices which are inherent in popular government. When the American people is intoxicated by passion, or carried away by the impetuosity of its ideas, it is checked and stopped by the almost invisible influence of its legal counsellors, who secretly oppose their aristocratic propensities to its democratic instincts, their superstitious attachment to what is antique to its love of novelty, their narrow views to its immense designs, and their habitual procrastination to its ardent impatience… Scarcely any question arises in the United States which does not become, sooner or later, a subject of judicial debate; hence all parties are obliged to borrow the ideas, and even the language, usual in judicial proceedings in their daily controversies. As most public men are, or have been, legal practitioners, they introduce the customs and technicalities of their profession into the affairs of the country. [emphasis added].

A lawyerly affinity is hardwired into America’s political DNA. The American executive is checked by congress, it is checked by the judiciary, it is checked by a free press, it is checked by elections, and it is checked by onerous proceduralism, incoherence, and capacity constraints. There are so many checks, so many veto points within the political system and arising through its interface with society, that American government can be accurately described as a “vetocracy.”

One must look beyond the 1970s to understand why America struggles to build today. As Wang observes, “Chinese would recognize something in Robert Moses.” But they would not have recognized the obstacles he faced even in the period we recall as America’s breakneck growth era. To build, Moses had to become “the greatest bill drafter in Albany,” outmaneuver scores of lawyers and legislators, position himself as a node linking federal, state, and city government, assemble perhaps the most capable team of engineers and architects (and legal advisors) in the world ready with detailed blueprints at a moments notice to seize public funds and deploy them, embed public authority charters into bond issuances to entrench his dominion, and consolidate and discipline a comprehensive pro-building coalition.

The backlash against him, for better and worse, closed off the loopholes and avenues he created or exploited, making it that much harder to build. It is fitting that Why Nothing Works opens with this blunt epigraph: “We are at a moment of history. You could have Robert Moses come back from the dead and he wouldn’t be able to do shit.” Thus my own hypothesis:

A tentative conclusion from reading Power Broker (1974) in conjunction with Abundance and Why Nothing Works (2025): American inability to build (esp. public projects) is a much deeper feature than the adversarial legalism and regulatory expansion of the 1970s, which the latter books finger. Before Moses arrived no new bridge had been built in NYC in a quarter century. No new arterial highway in fifteen years. The people cheered as he demagogued about cutting through “old hacks” and “red tape” bureaucrats back in the 1930s. The building bonanza of the 1930s and 40s seems the deviation. An inability to build more like the norm. Perhaps exceptional circumstances permit one or two major bursts and deviation from trend per century.46

A Developmental State with American Characteristics?

In one of my favorite bits in the book, Wang notes China’s People’s Daily has declared that “no matter how developed China becomes, it will always remain a developing country.”47 America should follow suit, he argues—and I agree. Forego the false consciousness of having arrived at some terminal stage of development. Embrace developing! Maybe America should even pursue developing country status in the WTO?

As China moves beyond its breakneck era, calls for an American industrial policy are back, with some urging an “industrial policy with American characteristics.” This is a position Breakneck’s author supports. One could even borrow from de Tocqueville in saying a fair few Americans today are “intoxicated by passion” for industrial policy. And is it so wrong? To spike economists’ post-industrial, service economy Kool-Aid with a little industrial-fetishism? If we all get a little intoxicated, the lawyers will sober us up.

Yet the more pertinent question remains not whether America ought to pursue such a policy, but rather our “lawyerly society,” where vetocracy has long substituted for developmental bureaucracy, can. Looking to China can provide only the most cursory of inspiration. In times like this, one sometimes recalls the misbegotten pining of European elites like Voltaire for the system of the Qing mandarinate.48

China cannot and should not serve as a model to imitate, as Breakneck notes. But it can serve as a spur to return to the real wellspring for imagination: our own history.

I still remember my middle school visit to the Hoover Dam. A project begun in the late 1920s and early 30s and which stood at the gateway of America’s growth era. Joseph Stevens’ 1983 history of that project concludes with a rousing reflection on his subject that remains strikingly apropos today:

In the shadow of the Hoover Dam one feels that the future is limitless, that no obstacle is insurmountable, that we have in our gasp the power to achieve anything if we can but summon the will. Some try to suppress this feeling, thinking that it is naive to be enthralled by an engineering marvel, dangerous to be seduced by twentieth-century technology, which cynics say is untrustworthy, exploitative, and destructive of the environment and the human spirit. But in the clear desert light of Black Canyon, guilt about the deeds of the past and doubt about the promise of the future shrivel. The romance of the engineer still lives in the graceful lines and brute strength of Hoover Dam.49

Despite this poetic elegy to the engineer, one feels today that our great developmental landmarks are more like relics of the past. Though these sites are still destinations for tourists and school field trips, where children stare up at massive concrete walls and and walk around giant turbines, they are more like a trip down memory lane than inspiration for the future. If today one wanted the inspiration of a modern monument to American development, where should one go? (Half-sarcastic answer: China).

One need not submerge a county like Wushan to keep alive a sense of developmental dynamism. But it would be nice if America could render Dan Wang’s sadly accurate statement—“Americans are no longer able to appreciate that a physically dynamic landscape creates a sense of progress”—a relic of a bygone era.

Concluding Thoughts

One way to think of Breakneck is as an introductory China book. I myself thought multiple times: “my parents should read this.” I hope Breakneck succeeds in getting people to think about China and America in the manner it aspires. If I overhear people chatting about “engineering states” and “lawyerly societies,” I would be happy.

Another , related, way of reading Breakneck is a China focused version of Abundance, tempered in its middle chapters with requisite cautionary tales (One Child Policy and Zero COVID). I can already envision the media circuit and an appearance on the Ezra Klein Podcast. The book wants America to build abundantly again and to take inspiration from China in doing so. I am sympathetic. But in so far as the book aims at a more specialized policy-making audience whose views are less malleable to Breakneck’s vibes, I’m not sure if the book will find converts. We will see!

But a final way, my preferred way, to read Breakneck is as a memoir deftly interwoven with the broader political-economic tumults of the day. The final chapter—which I will not spoil nor do the disservice of re-rendering here—is a touching reflection on the author’s family history, on paths taken and not taken, and on what the pursuit of happiness, human flourishing, and the good life might mean in different cultural contexts and across generations. The ability of the author to weave personal experience into broader stories and relatable heuristics, making them memorable for a general audience, is the great feat of the book.

For my own purposes, though, I’ll forego calling China an “engineering state” and stick with the much less sexy heuristic: a Leninist developmental state with Chinese characteristics. One that is moving beyond its breakneck industrial prime, facing similar dilemmas America confronted in the 1960s and 70s, and improvising its own Leninist answers.

References

Joseph Needham et. al, Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 4 Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3 Civil Engineering and Nautics, p. 211.

Equally impressive is the fact that nearly 98 percent of the Chongqing–Wushan track consists of bridges or tunnels bored through mountains. Thirty years ago, reaching Wushan from Chongqing would have taken no less than a full day, and likely been subject to the mercy of river and weather

Sources: 重庆日报, “这条高铁为啥被称为“地铁式”高铁——郑渝高铁郑万段背后的故事”, June 14, 2022, https://jtj.cq.gov.cn/sy_240/bmdt/202206/t20220614_10810157.html

and 萍萍 , “重庆到巫山怎么坐车?重庆到巫山公共交通指南, 本地宝”, October 31, 2014, https://cq.bendibao.com/tour/20141031/48270.shtm

And once I got out, some parents and older gentlemen struck up a conversation with me. When I told them I studied China’s economy we engaged in a half hour long discussion on central-local debt, among other issues.

中国青年报, “公社大楼的前世今生”, August 31, 2011.

https://zqb.cyol.com/html/2011-08/31/nw.D110000zgqnb_20110831_1-08.htm

人民日报, “繁荣的中国就是世界的机遇”, March 20, 2024.

https://paper.people.com.cn/rmrb/html/2024-03/20/nw.D110000renmrb_20240320_2-20.htm

Corey J Byrnes, Fixing Landscape: A Techno-Poetic History of China’s Three, 2019, p. 2.

Academics have made the Three Gorges, and hydraulic projects generally, subjects of their work. Lieberthal and Oksenberg’s foundational Policy Making in China (1988) is a prime example, devoting its entire 6th chapter to the pre-decisional policy process. Andrew Mertha’s (2008) book China’s Water Warriors is an example of a broader look at water project political contestation, helping bridge from “fragmented authoritarianism” to “fragmented authoritarianism 2.0” by bringing in nascent civil society (in a manner that is itself now dated). One can find all manner of reporting on the Three Gorges and its pros and cons, as in this CNN piece.

For the terminology used in the paragraph, and for a good review of both Chinese and English literature on the subject of Three Gorges resettlement (albeit from an overwhelmingly critical deconstructivist lens), see this very interesting recent master’s thesis: Jingyi Chai, The Role of Law in Shaping Resettled Identity: A Case Study of the Three Gorges Project, Lund University, 2025, https://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=9192790&fileOId=9192791.

Interestingly, even in this critical review, the author notes (p. 10-11) that much of the literature notes that “long-term outcomes might have been better than initially expected.”

Of the dozen or so residents I chatted with, everyone—and everyone they knew—claimed to be very happy with the results. Part of the reason, no doubt, is that many of the original inhabitants liable to be least satisfied were resettled elsewhere years ago.

Relevant to later discussion in this essay, the author also argues that: “a managerial tendency can be observed in Chinese literature, where studies often follow a problem-solving pattern, concluding with suggestions for improving legal or policy frameworks…the problem-solving paradigm sometimes views them [residents] and not the resettlement as the problem. For example, Liu and Lei (1999) claimed that the government should strengthen publicity and education to help resettled people lower their expectations and actively adapt to the new environment. The temporal overlap between influential Chinese literature and the implementation of resettlement projects also suggests the effect of a managerial approach— attention to the resettled population diminishes once the relocation is concluded” (p. 11-12).

Deirdre Chetham, Before the Deluge: The Vanishing World of the Yangtze's Three Gorges, 2002, p. 19.

F. W. Mote, "A Millenium of Chinese Urban History: Form, Time, and Space Concepts in Soochow." Rice Institute Pamphlet - Rice University Studies, 59, no. 4, 1973, p. 51. https://hdl.handle.net/1911/63136.

Simon Leys, The Chinese Attitude Toward The Past, in The Hall of Uselessness: Collected Essays (New York Review Books Classics).

Deirdre Chetham, Before the Deluge: The Vanishing World of the Yangtze's Three Gorges, 2002, p. 22-23

For more color: “Some of the river towns, like Xituozhen across the river or Wushan downstream, with its desperate energy, seem to suffer from a widespread exhaustion of spirit that is hard to define but immediately recognizable. It is a kind of weariness that tends to prevail in places where opportunities are few, nothing is clean, and there is a sense of decay and decline. Walking through some of the towns on the Yangtze re- minds you of Walker Evans's photographs of rural, depression-era America in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, a kind of dusty resignation that suggests en- durance and possible survival, but little in the way of hope” (p. 12)

“There is a saying in Chinese that means "hard places breed hard people." Wushan is one of those places. With a population of 70,000, it is the largest city [sic] within the Three Gorges, one with a rough past and an uncertain future… Wushan combines the harshness of rural Sichuan poverty and its legacy of isolation, unemployment, and malnutrition with the squalor of a medieval port city…

Wushan is ranked among the poorest counties in China by both the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture and the World Bank, a list that includes places with a large proportion of people whose income is less than one U.S. dollar a day. Along the river, being poor is not much of a distinction, but Wushan is known for other things, mainly for what the Chinese call being luan, or chaotic and disorderly. This can mean many things, but here it includes the open prostitution and close-to-the-surface anger that is manifested in frequent street fights and tearoom brawls. Wushan is the only town in the gorges that can boast of several murders in recent years, and it is one of the rare ports where captains sometimes restrict their crews to the ship while docked. (p. 17)

Though we did not go see it, there is also a much publicized “airport in the clouds.” These are undoubtedly questionable resource allocation decisions. As to whether they are worthwhile, see my opinion in text.

For what it’s worth: On the theme of sex and gender, there was a very notable divide at the lunch. The boys sat closest to me and stayed together. The girls sat at a separate table. The boys were loud and most of them unabashed in asking questions. The girls were quiet and mostly would only engage when I would ask them questions directly. In my experience, gender divides—particularly wherein the man does all or most of the talking—appear much starker as you move down China’s administrative ranking (tier 1 → tier 2 and on to counties and county-level cities). Of course, this is an amateur sociological observation and my own “positionality” biases these observations immensely. Others may have contrasting perspectives, but I suspect this holds true.

See: 中国百度百科,条目《神女十二峰》, https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E7%A5%9E%E5%A5%B3%E5%8D%81%E4%BA%8C%E5%B3%B0/2974107

中国百度百科,条目《瑶姬》, https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E7%91%B6%E5%A7%AC/9420536#sup-6

搜狐,文章《巫山神女:除恶龙,助大禹治水的女神,为何床笫之事也与她有关?》,发布于 2019-09-08, https://www.sohu.com/a/339642056_662487

In his book on the subject, buried in an endnote, Mark Edward Lewis notes the distinctness of the myths in this part of China: “The tradition that Yu was assisted in his work by dragons is also recorded in local histories from late imperial China and in oral traditions still circulating in the Three Gorges region. See Yuan, Zhongguo shenhua chuanshuo, p. 492 note 22; Yuan Ke, Zhongguo gudai shenhua (Shanghai: Shangwu, 1957), p. 19.” See: Mark Edward Lewis, Flood Myths of Early China, 2006, p. 191.

Corey J Byrnes, Fixing Landscape: A Techno-Poetic History of China’s Three, 2019, p. 36.

“What the primitive 'sand-heap' (to appropriate Sun Yat-Sen's phrase) could not do, the forced levies of proto-feudal 'high kings' and their enfeoffed lords could; and what they in turn were incapable of accomplishing could be done by the high officials of the united empire from Qin times onward, with their maps and surveys and developed technique by feudal and then dynastic rulers for example, suggests that early dynasties.” Joseph Needham et. al, Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 4 Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3 Civil Engineering and Nautics, page 249-251.

See Mark Edward Lewis, Flood Myths of Early China, 2006;

and Joseph Needham et. al, Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 4 Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3 Civil Engineering and Nautics, page 211.

江泽民,把三峡工程建成世界一流工程, 1997, http://www.reformdata.org/1997/1108/5722.shtml

Corey J Byrnes, Fixing Landscape: A Techno-Poetic History of China’s Three, 2019, p. 39.

In addition to educational, traveling to China’s lesser known provinces, cities, and counties is also fun.

At one point, Wang writes: “By traveling as often as possible to smaller cities—some that are little more than urbanized industrial parks—I grasped something that most Americans, and even many Chinese, do not: Going to little-known cities in China is fun.” I feel this is true of my experience as well.

One of my favorite ways to visit a new city in China is to make my way to the outskirts—ideally as much of the trip on rental moped as possible—and poke around various “development zones” (开发区), admire the layouts and the industrial infrastructure mostly paid for by LGFVs, and chat to people. Sometimes I had a specific mission in mind, as when I showed up at legendary glycine producer DongHua JinLong unannounced and got a tour of their premises.

MOE doesn’t seem to break it down anymore but the 1999 distribution was: 机械 Mechanical Engineering: 17%; 电工 Electrical Engineering: 10%; 电子与信息 Electronics & Information: 29%; 土建 Civil Engineering & Architecture: 12%. http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_sjzl/moe_560/moe_571/moe_563/201002/t20100226_7792.html

Frank Pieke, Market Leninism: Party Schools and Cadre Training in Contemporary China, BICC Working Paper, 2007, p. 8 https://cpb-eu-w2.wpmucdn.com/blogs.bristol.ac.uk/dist/0/168/files/2012/06/03-Pieke.pdf

The Central Party School provides training to cadres up to the Vice Ministerial ministerial rank, higher ranked officials (including members of the Politburo) receive their ongoing training through study sessions, special meetings and briefing sessions, and conferences.

See also: Charlotte Lee, Training the Party: Party Adaptation and Elite Training in Reform-era China, Cambridge University Press, 2017; David Shambaugh, Becoming a Ganbu: China’s Cadre Training School System, 2022.

Also some recent personal accounts, including this riveting experience: “Wang Guocai, a judge at Beijing No 2 Intermediate People's Court, received one week's education at the Jinggangshan academy in June 2016. He said he benefited greatly from visiting local revolutionary areas where veterans fought.

As part of the training session, he was asked to dress in a replica Red Army uniform to walk along a rugged path, which was a route taken by the army, a forerunner of the People's Liberation Army. He had to carry rifles, sacks of food, and complete several tasks along the 5-kilometer trail.

"I read about this path in history books, but I had never walked along it. I will never forget the experience, because I now better realize the hard lives the older generation lived in the revolutionary cause," Wang said.

He added that he was inspired by the activity. "The fact that soldiers and civilians supported each other so much during the revolutionary period shows that the Party is from the people and for the people," he said.

"As a judge, I realize that serving the people means upholding justice in every case and giving litigants easier access to legal services."

In 2019, Wang was made director of the court's trial management department, responsible for supervising judges in concluding disputes within a specified period and improving the quality of case handling.

"Thanks to theoretical studies and learning about history in Jinggangshan, I've been able to think big in my work and develop a more profound understanding about the role of our court in economic and social development," he said.

"Previously, I was like a sailor. Solving cases was my entire work. But now, I'm more like a helmsman, as I am required to lead judges on the right path and assist litigants through better services.”” https://www.bai.gov.cn/en/baiencpc/baienundercpc/202407/t20240721_3754038.html

James Burnham, The Managerial Revolution, 1941; John Galbraith, The New Industrial State, 1967; Lynn White et. al., The Thirteenth Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party: From Mobilizers to Managers, Asian Survey, 1988. The themes relate to Ted Kaczynski’s screed.

Though every chapter in Breakneck is thematically connected to the big idea, each also stands on its own, mirroring the style of the author’s beloved and well-known annual letters.

Wang discusses Xi Jinping and the Party leadership’s obsession with the “real economy” 实体经济 in pages 84-85. The chapter itself argues in this vein, warning against casting off the real in pursuit of the fake/virtual (脱实向虚), much as Xi himself explicitly stated at the 2021 CEWC that China should learn from Western countries and avoid the ills he associates with 脱实向虚, see here: 习近平总书记2021年12月8日在中央经济工作会议上讲话的一部分, https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-05/15/content_5690547.htm.

For Scott’s point see James. C Scott, Seeing Like A State, 1999; for the full elaboration of “industrial commons” and its importance to the American innovation and industrial base (and thus prosperity) see Gary P. Pisano and Willy C. Shih, Producing Prosperity: Why America Needs a Manufacturing Renaissance, 2012.

Breakneck expands the point with reference to Apple:

“if the iPhone were built in the United States rather than Shenzhen, then an American city—say, Detroit, Cleveland, or Pittsburgh—might be hailed as the hardware capital of the world. The follow-on innovations in consumer drones, hoverboards, electric vehicle batteries, and virtual reality headsets could have sprung from American firms. Engineers wouldn’t have to fly from Cupertino across the Pacific to reach their giant factories. They could iterate on product improvements closer to home…The United States must regain, at a minimum, the manufacturing capacity o scale up production that emerges from its own industrial labs. If it does not, continuing to value scientific breakthroughs rather than mass manufacturing, then it might lose whole industries once more—as it did by inventing the solar photovoltaic panel but relying on China to produce them. The United States likes to celebrate the light-bulb moment of genius innovators. But there is, I submit, more glory in having big firms making a product rather than a science lab claiming its invention. Otherwise, US scientists would once again build a ladder toward technological leadership only to have Chinese firms climb it” (p. 91-2).

“The capitalist system of production,” the Austrian school economist Ludwig Von Mises once wrote, is an economic democracy in which every penny gives a right to vote.” Attempt to interfere in the market’s allocation would, per this school of thought still highly influential among economists and U.S. policymakers, be egregious bureaucratic overreach. This, like much of this school’s writing, is oversimplified and can be easily complicated or refuted. But the book does not engage. Ludwig von Mises, Bureaucracy, 1944, p. 21.

Or in another instance warning that if America “does not recover manufacturing capacity, the country will continue to be forcibly deindustrialized by China…[so] America has to build to stave off being overrun commercially or militarily by China” (p. 226-7).

Susan Greenhalgh, Just One Child: Science and Policy in Deng's China, 2008

See also her articles and chapters: Susan Greenhalgh, Missile Science, Population Science: The Origins of China's One-Child Policy, 2005, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/china-quarterly/article/abs/missile-science-population-science-the-origins-of-chinas-onechild-policy/65D2C3C2BFFBB0334CB0A04D35BC4146

Susan Greenhalgh, Science, Modernity, and the Making of China's One-Child Policy, 2003, https://susan-greenhalgh.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Science-Modernity-and-the-Making-of-Chinas-One-Child-Policy-June-2003-PDR.pdf

From the May 4th movement and Mr. Science in 1919 to the communists championing of “scientific socialism.” Among the many misconceptions people have about China, one is a tendency to think of pre- and post-Mao China as representing a period of irrationality followed by pragmatism. But the one-child policy is a perfect example of the far more messy reality. As Greenhalgh herself argued, scientism became something of a new faith:

“The cyberneticists' extraordinary prestige and access to political power secured their preeminence in the struggles over population strategy… the natural science story gained its power and persuasiveness from a larger, historically developed cultural climate in which science has been surrounded by a kind of mystical awe. This quasi-religious attitude toward science infected the leadership, who took the population scientists' numbers as gospel truth. Students of contemporary China have documented a broad shift in China's reform-era culture and politics away from humanistic perspectives toward scientistic and technocratic ones (Suttmeier 1989; Li and White 1991; Hua 1995). The victory of the scientistic solution to the population problem must be seen as part of that larger sea change in the culture of Chinese modernity.”

Susan Greenhalgh, Science, Modernity, and the Making of China's One-Child Policy, 2003, p. 187-8, https://susan-greenhalgh.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Science-Modernity-and-the-Making-of-Chinas-One-Child-Policy-June-2003-PDR.pdf

The one-child policy fits the high-modernist check-list Scott devised perfectly: 1) administrative ordering that reduces and simplifies people to legible, and therefore controllable, numbers and quotas; 2) a rabid high-modernist ideology of cybernetics and scientism promising to “optimize” population; 3) authoritarian state power, a concentrated, Leninist Party-state capable of and willing to enforce compliance through coercion; 4) a prostrate civil society, no independent institutions capable of resisting or revising the policy.

James C Scott, Seeing Like A State, 1999, p.5.

For some of the history see the early chapters of Siddartha Muhkerjee’s The Gene: An Intimate History, 2017.

A bit more speculatively: I suspect Xi Jinping treated Zero-COVID not as a test run for closing the country, as some stated at the time, but rather saw it as a crisis to be overcome by whole-of-nation mobilization—a mission that galvanized the things he (and his father, for that matter) fetishize: unity, struggle, and the deindividuated melding of individuals into a Party-led whole. For a time, Zero-COVID offered the perfect opportunity: a genuinely useful, life-saving campaign that demanded total mobilization and immense sacrifice, while simultaneously showcasing and sharpening the Party as an “organizational weapon” — namely its capacity to bind the nation together in purposeful struggle.

Elizabeth Perry, 2019. “Making Communism Work: Sinicizing a Soviet Governance Practice.” Comparative Studies in Society and History https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/comparative-studies-in-society-and-history/article/abs/making-communism-work-sinicizing-a-soviet-governance-practice

Elizabeth Perry, 2024. “Blurring the Boundaries of Governance: China’s Work Teams in Comparative Perspective.” Comparative Political Studies, https://scholar.harvard.edu/sites/scholar.harvard.edu/files/perry-2024-blurring-the-boundaries-of-governance-china-s-work-teams-in-comparative-perspective.pdf

Marc Andreesen bellowed in a well known 2020 post: it is time to build again. Patrick Collison maintains a site noting how fast mega projects used to be built in America. Tanner Greer of the Scholar’s Stage has deconstructed with erudition a perhaps fundamental problem: we have lost the vigor, and the enabling institutions, of a culture that builds.

In passing it does also the broader common law system, “typical for anglophone countries.”

“The United States inherited a common law system typical for anglophone countries, in which judges have more discretion (relative to legislatures) to shape the law. It is no coincidence that housing and infrastructure costs are astronomically high across the anglosphere, including in the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and Ireland…I want to invoke the classic line by Professor Grant Gilmore, in a text often assigned to first-year law students: “The worse the society, the more law there will be. In hell there will be nothing but law, and due process will be meticulously observed” (p. 229).

Some like Dan Davies have elaborated this into a more precise issue, see his 2025 article for Niskanen “The Problem Factory” that notes the unfortunate incentives and problems that arise from the quasi-judicial approach to infrastructure building in anglo countries, which contrasts with continental Europe’s system of corporatist planning with a nodal state body capable of reducing uncertainty. As he notes: “And this raises a potentially uncomfortable paradox; in most other contexts, corporatism is considered to be a source of sclerosis in European economies, not a method of managing it. The smaller and more neutral administrative state in the Anglosphere countries usually allows greater flexibility and dynamism – even the large and diverse professional services industry is usually considered to be a strength rather than a weakness. Infrastructure may be a special case.” https://www.niskanencenter.org/the-problem-factory-preemptive-risk-aversion-in-infrastructure-planning-and-the-role-of-professional-services/