Industrial Colossus: China vs 1950s America

China's global manufacturing share to 2035

Chinese industrial maximalist Lu Feng argues that China today resembles the United States on the eve of World War I. But the analogy is faulty. China’s industrial strength—and its broader economic trajectory—is much closer to the United States of the 1950s.1

China vs 1950s America

Most striking is the convergence in urbanization rates. In 2024, China stood exactly where the United States did in the 1950s.

Vehicle penetration per capita fits a post-WWI interpretation as well.

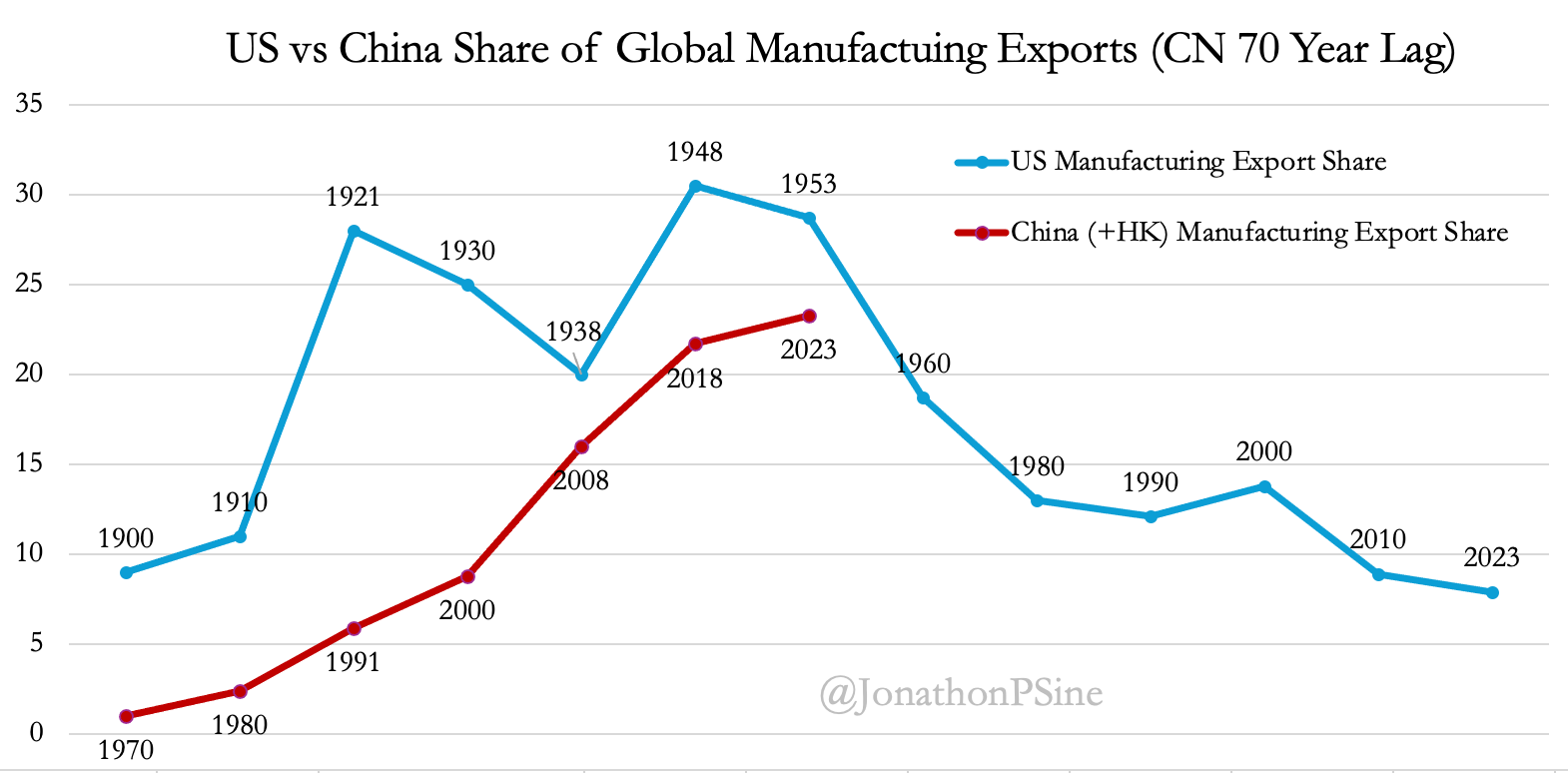

Now consider 1) the United States and China’s share of manufacturing exports and 2) share of total global manufacturing by value added:

If China were truly in the position America occupied before World War I, we should expect its share of global manufacturing to continue surging. At the very least, we might expect it to reach a 45 percent share of global manufacturing—a level the U.S. only attained after Europe’s industrial capacity had been devastated by World War II.

Rightsizing China’s Global Manufacturing Share

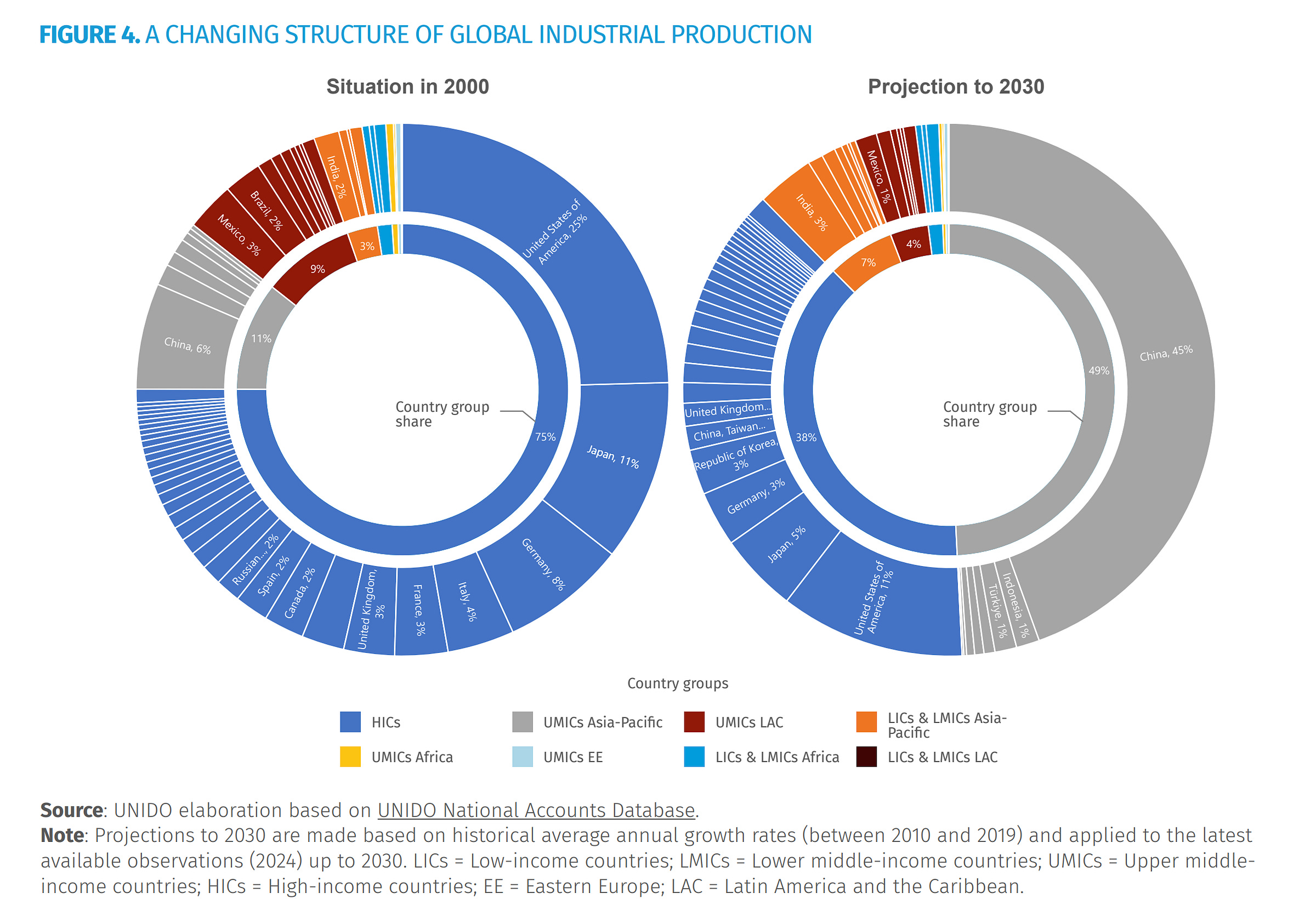

The claim that China will account for 45 percent of global manufacturing in 2030 has gained surprising traction, despite the fact that it is completely implausible.

The statistic comes from a 2024 UN Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) report on the future of industrialization. Inexplicably the authors chose to extrapolate a linear trend from 2024 to 2030 … based on average growth rates from 2010 to 2019.

But as the data—UNIDO’s own data, in fact—make clear, China’s growth in global manufacturing share has slowed dramatically. In the early 2010s, China was gaining roughly 1.5 percentage points per year (based on a five-year rolling average); today, that rate has fallen to just over 0.5 percentage points annually—about one-third the previous pace.

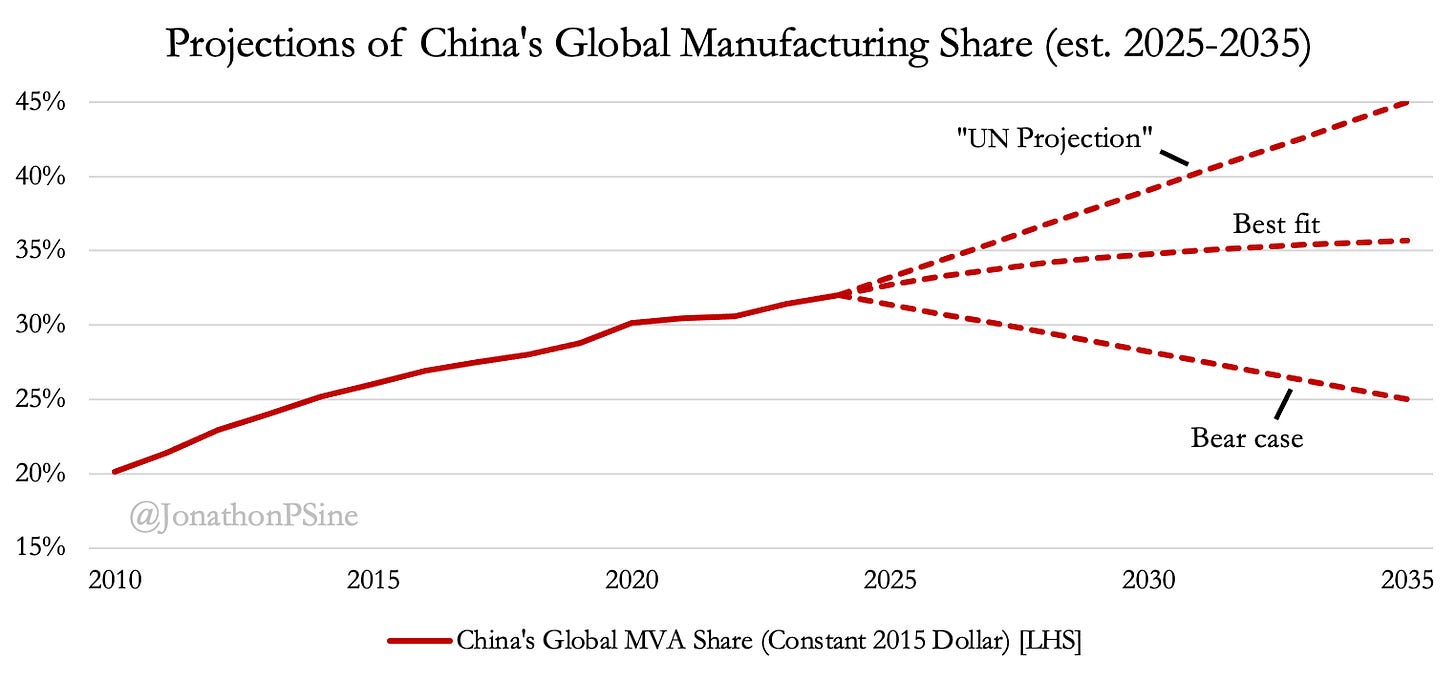

When using more reasonable assumptions, it quickly becomes clear just how far-fetched the idea of China reaching a 45% share of global manufacturing truly is—especially given how sharply it diverges from the current best-fit trajectory.

Below are three scenarios: the UN’s projection (which requires a 1.2 percentage point annual increase), a best-fit extrapolation, and a bear case that assumes a 0.6 percentage point decline per year.

Eagle eyed observers may have noticed the UNIDO report uses industrial value added (IVA) rather than manufacturing value added (MVA). Though commentators tend to casually conflate them, they are in fact two different series.

But using manufacturing value added, as I did above, is actually generous to UNIDO: China's global share of industrial value add is lower than its global share of manufacturing value add.

China’s industrial might is impressive enough without resorting to faulty analogies or inappropriate data projections. Yet, despite the ambitions of industrial maximalists and the bullish projections from organizations like the UN, China’s share of global manufacturing is likely near its peak.

There are global and domestic reasons to think this:

The Global Scramble for Industrial Power

Globally, since Reform and Opening, economic conditions have been uniquely encouraging of China’s industrial upgrading. Whether it be flying geese model technological upgrading, American outsourcing and free trade maximalism, or the opening of the WTO—trends have been uniquely accommodative. It seems unlikely the next two decades will be as accommodative of China’s manufacturing growth as the previous two have been. The medium-term future will most likely be marked by deepening economic fragmentation and a resurgence of economic nationalism.

The very fact of China’s rise as an industrial colossus contributes to the growing global scramble for production capacity. Developed countries will continue moving to protect their own industries and expand industrial policy. Developing countries will continue to strategically shield their markets and increasingly adopt the same type of playbook used by China and earlier industrializers—manipulating globalization to serve national goals and using targeted trade and industrial policies to climb the value chain, a process that for many countries China’s own rapid industrial rise seems to have suppressed. Countries are now launching unprecedented numbers of counter measures against China, according to the PRC’s own data. In the future, I suspect, the orderly free trade world of the WTO will continue to recede in relevance.

A global scramble for industrial might is on, unfolding in the shadow of a fading neoliberal world order. Is China’s manufacturing share really likely to surge again under these conditions?

The US and China: Back to the Post-Moses Future?

Domestically, consider that America began intensively counteracting the consequences of its own production-centric model in the 1960s and 70s—environmental degradation, regional, wealth, and income inequality, abuses of corporate power, and other negative externalities. Over the last few years, China has similarly grown serious about tackling the costs of its industrial ascent, with the common prosperity campaign only the most recent high visibility case.

A Gilded Age analogy between America and China remains popular, but a more interesting comparison is the 1960s–70s regulatory backlash that erupted in the shadow of Robert Moses. This era in America saw the creation of EPA, NEPA, and OSHA; the rise of innumerable other environmental and regulatory protections; growing anti-monopoly sentiment; and a broader backlash against the growth machine. The U.S. entered a phase of self-correction that brought many sorely needed quality of life improvements as well as constraints on local power brokers. But it also metastasized into an era of adversarial legalism and procedural fetishization that has made building anything difficult.

In some ways, China’s current turn mirrors this—marked by heightened scrutiny of local governments, a renewed focus on inequality, and regulatory crackdowns on large tech firms. It is China’s own post-Moses moment: a bid to constrain local discretion and tighten hierarchical control in the name of (Chinese-style) modernization. As Xi himself often puts it, power (by which he means other peoples’ power) must be "locked in the cage of institutions" (把权力关进制度的笼子里). A Leninist-inflected form of legalism and proceduralization?2

But where American dysfunction is defined more by ossification and encrustation of rules, procedural expansion, and innumerable veto points, China’s version of a post-Moses Leninist order is producing a different form of dysfunction—uncertainty born of increasingly pervasive yet fluctuating demands from above that leave local governments and firms groping through a fog of modernization mandates and diktats.

As an industrial maximalist, Lu Feng’s analogy is less analytical than instrumental: he wants to push China’s policy-makers to double-down on investment-led growth and industrial promotion. He is very explicit in his critique of recent policy.

In fact, Lu goes so far as to accuse China’s mainstream economists and economic policymaking establishment of having implemented policies designed to induce China to “commit suicide.” Here is the most important portion:

After the 2008 global financial crisis, the U.S. went further and blamed China’s “excess capacity” as the main driver of global economic imbalances (in other words, implying the financial crisis was China’s fault). But once this narrative reached China and was reinterpreted by certain domestic voices, it began to appear in Chinese policy language—in terms like economic imbalance, market clearing, and zombie enterprises—all of which actually originated in foreign discourse.

In the later period of the Biden administration, the U.S. once again employed a dual strategy of suppression and coercion—pressuring China with one hand, while persuading it to "commit suicide" with the other. It recycled the familiar accusation of "China’s industrial overcapacity," and once again, mainstream Chinese economists began seriously discussing the signs and causes of China’s supposed overcapacity—essentially reacting to foreign rhetoric. This time, however, the Party Central Committee was unmoved, and China did not fall into the trap.

In saying that the Central Committee did not fall into the trap this time, Lu is implying that Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao administrations did fall into the trap—particularly with Wen’s talk of the four imbalances 四大不平衡—and that Xi Jinping did as well by implementing the supply side structural reform in 2016 (供给侧结构性改革 is what interview actually asked him about).

I include an extended excerpt of the relevant interview below, in both Chinese and English, for those who want the full context:

观察者网:主流经济学界的观点认为,“供给侧改革”旨在调整经济结构,使要素实现最优配置,加之节能减排等做法也符合增长的长远利益。但是具体执行层面,这些措施确实是把双刃剑。在您看来,为什么这样的思维能够影响政策?

路风:这里也存在着国际因素。2005年,美联储主席伯南克在一次讲演中,把当时美国国际收支赤字迅速扩大的主要原因归咎于美国之外国家的“saving glut”(储蓄过剩),却只字不提美国当时正在中东和阿富汗进行耗资巨大的战争。虽然当时中美关系尚好,没撕破脸皮,但他指的是谁则一目了然,因为中国从本世纪之初已经取代日本成为对美的最大出超国。

2008年全球金融危机后,美国更指责中国的“产能过剩”是造成全球经济不平衡的主要原因(意思是金融危机怪中国喽)。但这些话术传到国内并经过一些人的重新解释,就在政策语言中表现出来了,如经济失衡、市场出清、僵尸企业等等概念,它们其实全是来自国外的概念。

拜登政府后期,美国对中国又采取一手打压、另一手劝其“自杀”的手法,再次编造“中国工业产能过剩”的老调,国内的主流经济学家跟着就开始煞有介事地讨论中国产能过剩的表现和原因,算得上是闻外人之风而动。只不过这一次党中央不为所动,中国才没有上当。

这里就产生一个问题,中国发展的议程是由自己还是由外人决定的?例如,2020年6月达沃斯世界经济论坛主席克劳斯•施瓦布在该论坛的官网发文说,

“全世界必须共同行动起来,迅速改造我们的社会经济的各个方面……不管是美国还是中国的每一种产业,无论石油、天然气还是高技术工业,都必须进行转型。”

关键的事实是,现在中国的工业规模比美国、欧盟和日本加起来的总和还大,所以施瓦布这句听似道貌岸然的话之矛头所向,不言自明。他在该文中还说:“我们必须为我们的经济和社会系统建立完全新的基础。”

也就是说,当中国发展到现在的水平时,当中国工业发展出全球竞争优势时,西方精英希望中国的所有成就都不算数了,想把取得这些成就的“基础”打碎了重新来一遍。如果说,西方过去做的主要是劝说中国“自杀”,那么在特朗普一上台就退出《巴黎协定》之后,在欧洲国家纷纷借口能源危机而推迟减碳之后,我们所有的中国人今天都在见证:特朗普正在打碎全球经济和社会系统的现有基础,目的是“让美国再次伟大”。

无论国际、国内的因素是什么,当“二分法”思维和限产之风开始弥漫之时,就是中国经济下行之日;限产体制持续多久,中国经济增速下行就会持续多久,因为它迫使尚未完成工业化的中国出现去工业化的进程。我们用国家统计局全部5次全国经济普查公报的数据来证明这个趋势。

Observer (Guanchazhe):

Mainstream economists generally believe that "supply-side reform" aims to adjust the economic structure so that factors of production are optimally allocated. Measures like energy conservation and emissions reduction are also seen as aligned with long-term growth. However, in practice, these policies are indeed a double-edged sword. In your view, why has this way of thinking been able to influence policymaking?Lu Feng:

There are also international factors at play here. In 2005, then–Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke gave a speech in which he attributed the rapid widening of the U.S. current account deficit mainly to a “saving glut” outside the United States—without a single mention of the massive wars the U.S. was waging in the Middle East and Afghanistan. Although Sino-U.S. relations were still cordial at the time and hadn’t publicly soured, it was obvious who he was referring to: by the early 2000s, China had already replaced Japan as the largest source of the U.S. trade deficit.After the 2008 global financial crisis, the U.S. went further and blamed China’s “excess capacity” as the main driver of global economic imbalances (in other words, implying the financial crisis was China’s fault). But once this narrative reached China and was reinterpreted by certain domestic voices, it began to appear in Chinese policy language—in terms like economic imbalance, market clearing, and zombie enterprises—all of which actually originated in foreign discourse.

In the later period of the Biden administration, the U.S. once again employed a dual strategy of suppression and coercion—pressuring China with one hand, while persuading it to "commit suicide" with the other. It recycled the familiar accusation of "China’s industrial overcapacity," and once again, mainstream Chinese economists began seriously discussing the signs and causes of China’s supposed overcapacity—essentially reacting to foreign rhetoric. This time, however, the Party Central Committee was unmoved, and China did not fall into the trap.

This raises a fundamental question: Is China’s development agenda determined by itself or by outsiders? For example, in June 2020, Klaus Schwab, founder and chair of the World Economic Forum, published an article on the WEF’s official website stating:

“All of the world must act jointly and swiftly to overhaul every aspect of our societies and economies... Every industry, from oil and gas to tech, in both the U.S. and China, must be transformed.”

The key fact is that China’s industrial scale is now larger than the combined total of the United States, the European Union, and Japan. So the true target of Schwab’s seemingly high-minded statement is clear. He also wrote: “We must build entirely new foundations for our economic and social systems.”

In other words, once China has developed to this level—once it has forged globally competitive industrial strength—Western elites now hope to invalidate all of China’s accomplishments. They want to destroy the very foundation upon which those achievements were built and start over. If the West’s previous strategy was to persuade China to "commit suicide," then what we’re witnessing now—after Trump pulled the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement and after European countries delayed decarbonization citing energy crises—is a campaign to smash the foundations of the global economic and social order in the name of "making America great again."

Regardless of whether the cause lies in international or domestic factors, once binary thinking and the logic of production restrictions begin to spread, that marks the beginning of China’s economic decline. And the longer this production-restricting regime persists, the longer China’s growth slowdown will continue—because it forces a process of deindustrialization on a country that has not yet completed its industrialization.

In fact the entire edifice of Chinese economic policymaking is evolving around these broader concerns. The basic line of the Party remains as it has been since Deng: economic construction as the center, and reform and opening and the four cardinal principals as the two basic points (一个中心,两个基本点). But in 2017, Xi changed the principal contradiction—mostly ignored by Western press, but very important to a Party-state that still utilizes Marxist dialectics. This change sets a broader mobilization mission for the Party-state. Rather than GDP-maximalism, cadres’ ambit is now far wider. This both represents a change to deal with genuine challenges of modernization, and Xi’s desire greater Party-state influence. I would not be surprised if the Party’s basic line changes at the next Party Congress in 2027 to reflect this.

Deng Xiaoping era (post-1981 to 2017)

Chinese (original):

我国社会主义初级阶段的主要矛盾是人民日益增长的物质文化需要同落后的社会生产之间的矛盾。

English (translation):

The principal contradiction in the primary stage of socialism is the contradiction between the people's ever-growing material and cultural needs and backward social production.

Xi Jinping era (from 2017)

Chinese (officially revised at the 19th Party Congress):

我国社会主要矛盾已经转化为人民日益增长的美好生活需要和不平衡不充分的发展之间的矛盾。

English (official translation):

The principal contradiction facing Chinese society has evolved into the contradiction between unbalanced and inadequate development and the people’s ever-growing needs for a better life.

This is bluntly a very vague and vibes-dependent argument. The institutional paradigms in the US and China (common law tricameral vs leninist unitary) are basically as different as they possibly could be, and trying to draw 1-to-1 analogues between the two is like comparing apples to octopi. It's necessary to take the long view and compare the historical norms of the two systems before attempting comparative analysis.

[I know you know how a Leninist party works; I'm doing this as a preface not a lecture]

The Leninist party is essentially a nested expansion of committees. One committee controls several more committees at the level below, who each individually control several more committees at the next level below, etc. At every level of the bureaucracy, party members have a quasi-legal, or in some cases literally legal, obligation to follow the directives of the committee responsible for organizing the actions of that level (there are exceptions but this is true for the large majority). And this committee is obligated to follow the directives of the committee on the next level up, which itself has to follow the orders of the committee at the level after that, etc.

If this sounds reminiscent of a military organization that's not a coincidence. The CPSU's organization was originally foraged by the necessity of compartmentalization under Tsarist persecution, and was later refined into its modern form under the existential pressure of the Russian civil war. It was retained afterward by Stalin because the organizational structures meant to facilitate the mobilization of scarce resources for warfare also happened to be excellent at mobilizing scarce resources for rapid industrialization and the development of essential defense technologies. The same is true for the CPC post-1949.

Point is, the Leninist party is a system designed and shaped by the necessity of 'concentrating resources to do big things', specifically under conditions of intense scarcity and existential threat. The obvious glaring agency problems of such a massive and all-encompassing bureaucracy are tolerated because the circumstances grant its capacity for rapid mobilization an overriding importance.

That's the challenge for Xi: the system he inherited was made for warfare and Stalin-esque industrialization, but decades of peace and rapid development had seemingly robbed it of its purpose, resulting in a perilous loss of elite cohesion, and governance-wide paralysis from corruption and institutional fragmentation.

Xi is trying to reshape the party's governing institutions so that it can still play to its coordination and resource-mobilization advantages while effectively mitigating its principal-agent flaws; basically everything he does flows from this:

Empowering the CCDI and institutionalizing its role in everyday governance, merging local-level tax administrations with that of the CG, insulating the judicial hierarchy from the authority of local governments, formalizing and expanding the leadership role of party committees in the SOEs, the creation of special bonds for local governments that require central review and approval, ending the RE cash cow, creating several new top-level committees to coordinate policy execution between different government bodies, and now just a couple weeks ago clearly delineating the jurisdiction between those committees so they can function without his constant personal oversight. The list goes on.

As you noted, while these measures do restrict the exercise of power by people lower in the hierarchy, they still leave no real constraint on that of Xi or the PSC as a group. In fact, they actually enhance the latter two's power by heavily surveilling lower-ranking actors and constraining their discretion such that they have little choice but to as they are told.

Your contention, and that of others like Yuen Yuen Ang, is that this will lead to a period of stagnation as local bureaucrats are scared out of taking initiative in policy implementation and instead choose to keep their heads down and do nothing. I think this is severely misled for two reasons:

First, the organization department exists. The party is not somehow obligated to indefinitely keep officials on who take no initiative and make little effort in carrying out the center's orders. The idea that "the harder the center pushes, the more apathetic they [bureaucrats] will become" is a thought-terminating cliche akin to ultraprogressive arguments that enforcing the law is stupid and pointless because it will just make people try harder to get away with it.

China is a large country inhabited by many Chinese. It has no shortage of highly educated and ambitious young people ready to begin the governing career by taking the soonest available village post.

In other words, local officials will have to deal with it. Are the center's demands very heavy and sometimes downright unfair? Yes. But power is an immense privilege and their was never any guarantee of total fairness in their responsibilities. Xi's message is to figure it out, and if they can't, the OD will sweep them away and very quickly find someone who will.

Second, it must be recognized that, as an economy changes, the optimal governing techniques for developing the economy will change as well. There is no reason that what worked well in 2005 should still be what works best today. Therefore complaints about Xi's policies inhibiting "local experimentation", to the extent they were ever grounded in fact, are still unwarranted. The Chinese economy is not what it was 20 years ago. Why should it be taken as a given that the economic governing practices of that time are optimal for the present-day Chinese economy? Yuen in particular likes to treat this as so obvious that it should go without saying, but it really really isn't.

If one cuts through the party jargon, the main thesis of Xi's thought on the economy is this:

As the economy develops, the structure of its production matrix changes.

The overriding trend in economic development is for size and connectivity of the production matrix to gradually and irrevocably increase.

Therefore, given the increasing degree of complexity and interdependence of a country's industrial structure as it develops, it follows that the economic policymaking of local governments must be increasingly subject to top-level design and coordination so as to ensure that this complexity and interdependence is properly reflected in the government's actions.

Thus while it may seem to observers that many of Xi's governance reforms are arresting economic growth and """dynamism""", he is in fact priming the party for effective long-term governance of an increasingly mature and interlinked industrial economy where the indigenous generation and diffusion and new technologies is paramount.

Great piece!

It's understandable given UN politics what bias their estimates would have, it is ofc important to have a more calibrated view out in the more thoughtful media.

The Real GDP per capita numbers I usually look at to gauge "who's where in development" also seem to match the 40s-50s story.

I'd be interested in seeing (and reading about) more about how the differences in the Chinese model/society/political structure might affect these "diminishing focus on manufacturing" and "more attention to environment/social impact of it" trends. I feel with their system they might be less flexible than the US one was, and to an extent that's my impression of what happened: how far they let the construction bubble go, the relatively slow and limited turn to "environmentalism" and the ilk and remaining commitment to Deng model past what some commentators would've seen as most prudent (though maybe this is incorrect if they are still in the 40s-50s not 60s-70s) And ofc they'd have the US lessons in mind, not wanting to end up with quite our NIMBYism and ossification.

I'm not sure to what extent Chinese current competitive landscape is that much worse than the US one after 40s: after all it was much less of a free trade era, Europe was rebuilding, Japan started to rise. Are their competitors really worse than Germany and Japan that US faced, and trade limitations more?..

I'd also like to see some thinking about "capacities" and how that would interact with GDP per capita: US had a much smaller fraction of the world population in 1950 than China does now, facing a more "unsaturated" market (at least in terms of practical limits if not buying power). This kinda matches the story of "China having to go higher in technological sophistication/product value add earlier in development/richness than US did": British could get away with selling pins to colonies, US could do cars and appliances or whatever it did in 1950, with few competitors, it's good to be first, and with those probably costing much more relative to natural resources and labor than they do now (and that Chinese current wares do?..). Eg, is China facing more environmental impact per $ value add in manufacturing than US did given more market saturation?..