From Reform to Ruin in the USSR

The Soviet Collapse: A Tale of Botched Reform or Entrenched Bureaucracy?

“A nation so poorly prepared to act independently could not attempt total reform without total destruction. An absolute monarch would have been a less dangerous innovator.” – Alexis de Tocqueville

“History is a capricious lady. But I hope that it will judge me fairly.” – Mikhail Gorbachev1

The Helpless and the Reckless

The Soviet reform experience remains a repository of historical lessons. But are we learning the right ones? This essay will assess the role of one such debate: that of entrenched interests in the demise of the USSR.

Most agree deep problems in the economic system were at the root of the Soviet downfall. But the direct and proximate cause of collapse remains an object of debate. Did powerful bureaucratic interests make reform impossible, or was the reform process botched? How responsible was Gorbachev for the collapse? How much power did he even have in a late-stage Soviet system?

These questions run through the heart of a debate between two accounts of the Soviet demise, which I term “helpless” and “reckless” narratives. They find their clearest expression, respectively, in Chris Miller’s (2016) Struggle to Save the Soviet Economy and Jerry Hough’s (1997) Democratization and Revolution. This essay puts these narratives into combative dialogue.2

At the center of this analysis are assessments of the General Secretary’s power as well as the role and influence of “entrenched bureaucratic interests” within a Leninist system. Throughout, the essay suggests potential lessons—and pitfalls—relevant to China analysis today. It concludes with my summary of what went fatally wrong in the USSR.

The Power of the General Secretary

The question of the General Secretary’s power and capacity is fundamental to an analysis of the Soviet reform failure.

The “helpless” narrative in Struggle does not mince words in its characterization of Gorbachev’s relative power: “The archival material presented here…shows that Gorbachev was just one actor among many in the fragmented Soviet political system. He was far weaker than nearly anyone realized. The policies of the perestroika era can only be understood with reference to the political forces that obstructed Gorbachev at every turn.”3 In the conclusion, we are told: “Gorbachev inherited a system in which economic lobby groups played a larger role than ever before. Yet his powers as head of the Communist Party were weaker than any Soviet leader since the Bolsheviks took power in 1917.”4

This framing of the Soviet General Secretary as weak is, as Jerry Hough contends, “a striking reversal of our older view of the Soviet leadership” that saw the leader as a potent dictator of a totalitarian system.5 Hough was himself a leader of the revisionist, pluralistic interest school of Soviet politics that sought to undermine the overly simplistic totalitarian model.6 Then, however, Hough began warning that the field, beginning in the 1980s, was erring too far the other way. The “helpless” narrative lineage thus traces back to a framing that took hold in Western analysis around the time of Gorbachev’s ascension in the 1980s, in a manner not entirely dissimilar to the rise of the “collective leadership” and “fragmented authoritarianism” frameworks in the China field in the 80s and 90s.7

The assumption that Gorbachev was but one weak player in a fragmented political system demands investigation. The theoretical basis for this claim of Gorbachev’s weakness is at best suspect. Leninist systems are more often considered leader friendly, with the General Secretary particularly powerful.8 But it is not always the case that General Secretaries dominate the scene, as the example of Hu Jintao in China demonstrates.9 So a close analysis is warranted. But the evidentiary basis seems only to cast further doubt on this fundamental assumption of the “helpless” narrative. The evidence suggests, rather, that Gorbachev—somewhat like Xi Jinping today—was not just “one actor among many in the fragmented Soviet political system,” but rather a very powerful man in a uniquely powerful position.

Personnel as Power

Gorbachev became the secretary in charge of personnel selection under Andropov in 1983. In that perch he got to work selecting and replacing top-level regional party secretaries.10 Following two quick deaths—Andropov and Chernenko—Gorbachev was General Secretary by 1985, at the ripe young age of 54, and just one year out from a Party Congress. The February 1986 Party Congress would afford him the ability to make even more drastic personnel changes early in his tenure. Brezhnev’s “stability of the cadres” also meant the Politburo and broader Party-state administrative apparatus was filled with geriatrics ripe for forced retirement. Gorbachev, Hough writes:

“was quite fortunate in a number of respects…the mortality rate among members of the 1980 Politburo was high, and there were relatively few of the top officials of the Brezhnev era with whom Gorbachev had to deal. Moreover, Chernenko was a much easier man to follow than Andropov. Andropov accomplished little in his year in office, but he created the feeling that he would do something. Since he had made no compromises, his legend was larger than life, and no actual successor could match it. Chernenko, by contrast, cut such a pathetic figure that any successor would have seemed charismatic. The elite was worried about the political consequences of continuing stagnation, and there was a hunger for leadership after a decade of ill leadership.”11

Gorbachev quickly removed three out of ten full Politburo members, including his presumed main rivals (Romanov, who he was able to remove even prior to the Congress, and Grishin) and got five new members added who would come to form his core leadership team. Gorbachev got another three Politburo members added during a plenum in mid-1987.12 After additional reshuffling, “by November 1987 Gorbachev had laid waste to the old Politburo and Secretariat with a speed never seen before in Soviet history: eight of thirteen voting members had been newly elected since he came to power and nine of twelve Central Committee secretaries (and he himself, of course, was one of the survivors in each group).”13

Elite USSR Personnel Turnover (1982-1987)

By way of comparison, below you can see data on elite personnel turnover in the initial periods of power consolidation under each of the last four Soviet leaders.

Leadership turnover in leading party organs under Brezhnev, Andropov, Chernenko, and Gorbachev (initial months of power consolidation)

Personnel turnover across all ranks under Gorbachev (1982-1987) was nothing short of remarkable: 69 of 83 members of the Council of Ministers, the state’s executive body, were replaced; 9 out of 14 republican first secretaries; and 108 of 150 obkom (i.e. provincial-level) first secretaries were replaced.14 By 1990, “all but four of the twenty-five members of the Politburo and Secretariat had been elevated to their positions during his tenure. Likewise all but one CC department head, all republic party first secretaries, and 129 of 143 regional party first secretaries had been recruited since Gorbachev's rise.”15 Gorbachev was cleaning house.

Perhaps such rapid turnover is meaningless. Undoubtedly, not all of these replacements were simple Gorbachevian sycophants. But Gorbachev’s ability to undertake such massive personnel reshuffling does not comport well with an image of a “helpless” leader beset by entrenched bureaucratic enemies. More than likely, it points to the obvious: that the General Secretary was powerful.

Power’s Purpose: Slashing the Bureaucracy

What did Gorbachev do with this seeming consolidation of personnel-based power? He radically restructured and reduced the bureaucracy, seemingly at will. By early 1990, the number of central commissions and ministries were reduced from nearly 100 to 57. In 1987-1988 alone, ministerial bureaucratic staff at the center was slashed by a third, and between 30 to 40 percent of all ministry staff at the republic and oblast (provincial/state) levels were removed—millions of people.16 Meanwhile, in 1988, even the Party’s own full time staff at the center—the central committee apparatus of the CPSU in Moscow—was slashed by roughly a third, from ~2200 to ~1500.17

More importantly, Gorbachev neutered the traditional power of the Politburo and Secretariat by creating six new top-level decision-making commissions in September 1988. A divide and conquer approach, he distributed top-level decision-making power into more controllable spheres. Some may recognize this as the very same strategy Xi Jinping has pursued in China with the rise of LSGs and Commissions, which has helped him dominate the policy-making process.

Streamlining the Apparatus (1988)

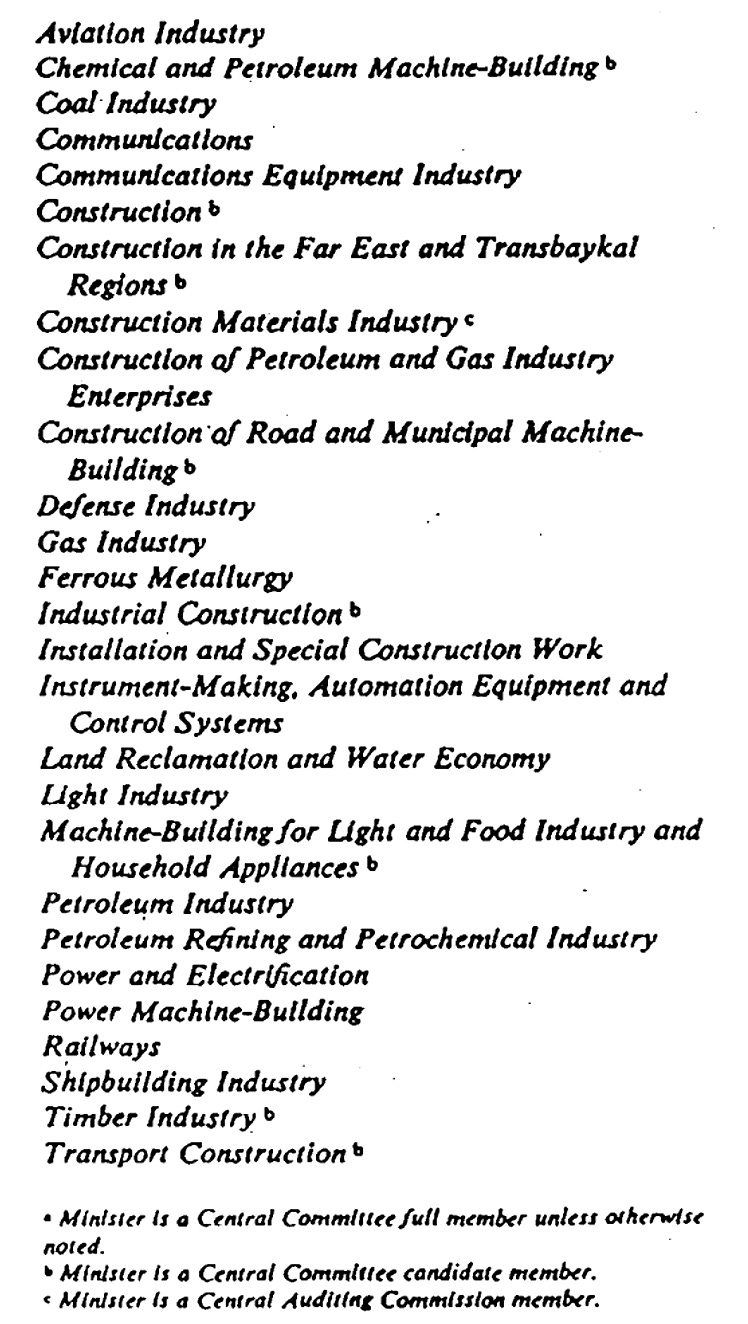

One move was particularly demonstrative of Gorbachev’s power over major bureaucratic interests. He abolished all seven of the branch economic departments in the Central Committee (aside from agriculture and defense) e.g., the Machine Building Industry Department, the Chemical Industry Department, and so forth (see figure above).18 In their stead, a singular “socioeconomic commission” was established. Gorbachev excluded every single major industrial minister from membership on the new economic commission, save one—the Minister of the Electronics Industry. As the CIA noted in their analysis at the time,

“Sovietologists believe that the industrial ministers on the Central Committee represent one of the most virulent sources of resistance to economic reform. Gorbachev appears to have scored a major victory in forming the commissions by managing to exclude from membership nearly all of these officials, including representatives of the following heavy and defense Industrial ministries [see figure].”19

Excluding Nearly All of the Industrial Ministers, Including the Following:

The decisive reorganization, the intelligence assessment concluded, “proved that he [Gorbachev] had the political strength to impose radical change on the party apparatus.”20 It went on to observe that “Gorbachev may hope that the commissions will facilitate reform of the Soviet system, but his overall goals appear to go far beyond simply creating a new administrative apparatus, extending to reducing party control in general and enhancing his own power.”21

The large-scale downsizing of the bureaucracy, major organizational restructuring, and minimization of top-level industrial ministerial influence do not sit well with the idea that Gorbachev was “weaker than any Soviet leader since the Bolsheviks took power in 1917,” as Miller asserts in Struggle. The opposite may actually be closer to the truth. John Willerton, a Soviet scholar who looked at this data in 1992, wrote: “Gorbachev's institutional powers as General Secretary and President have been vast; arguably, they have been greater than those of any Soviet leader since Stalin.”22

This recapitulation only scratches the surface of the organizational and institutional aspects of Gorbachev’s power. Yet this kind of discussion is missing entirely from Struggle. Gorbachev’s weakness is merely assumed. Hough, however, warned back in 1997 that this was not a safe assumption to make: it “is crucial to understand the basic point about Gorbachev's great power in 1985-86. Otherwise one would grossly exaggerate the ability of the conservative opposition to resist change, which Gorbachev's minions were emphasizing at the time to deflect criticism from him and to explain the decisions he was not taking.”23

The cavalry of archival material that Struggle promises never quite seems to substantiate the claims of Gorbachev’s great weakness. Instead, his weakness is either assumed or quotes from memoirs, particularly those friendly to Gorbachev, are mobilized in support of the narrative.24 Yet in the introduction to Struggle we are warned: “much of our understanding of Soviet politics during the perestroika era is based on poorly sourced media reports and untrustworthy memoirs” [Emphasis added].25

No doubt the institutional apparatus was unwieldy, complex, and resistant to some of Gorbachev’s restructuring. But that did not stop him from turning over most of the top personnel, undertaking major restructuring, and slashing the bureaucracy’s size substantially. This does not necessarily mean he made it work better, but it does indicate he had quite a bit of power.

Fear and Loathing in the Kremlin: The Case of the Coup Against Comrade Khrushchev

The 1964 coup against Khrushchev serves as a core pillar of the “helpless” narrative.26 In Struggle, Miller writes: “If he [Gorbachev] crossed too many powerful interests, he could have easily been forced out, retired, jailed, perhaps even shot. Gorbachev’s predecessor Nikita Khrushchev was toppled in a military backed coup…Gorbachev knew he always stood on a knife’s edge. Any wrong move could cost him his job, or worse. Many were surprised that the August 1991 coup against Gorbachev took so long to come. Within the USSR, it was no secret that Gorbachev’s policies were controversial and the politics treacherous.”27 He considers the validity of this fear determinative of Gorbachev’s economic reform choices:

“Gorbachev’s embrace of market reform was dangerous, politically and economically. The immense power of economic interest groups in Soviet politics severely limited the number of policy choices that were realistically possible. By the end of 1988, Gorbachev had gone all-in on a risky gamble. Balancing the budget with tax increases, spending cuts, or price increases would have been politically devastating. Both he and his allies believed such a strategy would have resulted in his removal from power, like Khrushchev before him.”28

The underlying assumption appears to be that Khruschev’s economic reforms ruffled the feathers of so many entrenched interests that it galvanized a coup against him. Hough contends that this framing is quite questionable, as “the conventional analysis of the Khrushchev era never adequately distinguished between conflicts over policy and conflict aimed at a change in leadership.”29 There was, he writes:

“a failure to distinguish style from substance. Various Politburo members disagreed with different parts of Khrushchev's policies, but they all hated his way of operating. Khrushchev was impulsive. He conducted a new reorganization every year. He announced decisions without having the staff investigate and prepare them properly, let alone the Politburo fully discuss them. In short, he was a lousy boss to work for, even if you agreed with many of his policies. A good deal of the so-called conservative opposition to Khrushchev simply wanted a more cautious approach—that is, more consistency, more consultation, less risk-taking. Much of the early analysis of the Brezhnev period labeled it "Khrushchevism without Khrushchev.””30

The most recent and authoritative compilation of evidence on the motives of the coup plotters, meanwhile, finds that the coup was not about policy at all, nor a result of Khruschev galvanizing entrenched interests against him with his disruptive bureaucratic reforms. As the author, Joseph Torigian, writes: “the main factor behind Khrushchev's removal was not policy differences or failures but his increasingly aggressive position, which forced his opponents to fight for their political lives.”31 Namely, Khrushchev seemed to be planning to “push up” a new group of young cadres and spoke incerasingly openly—and rudely—of replacing Presidium members, including Brezhnev.32 In this account, while there was generalized discontent with Khruschev’s bullying and dictatorial style of the sort highlighted by Hough, what most galvanized the plotters was fear that they were themselves on the verge of being ousted by Khrushchev.

Even still, the entire coup was far from inevitable and beset with contingency. Khrushchev was even informed about it by his son but, skeptical of the claim, did not act with urgency to counter it—missing a chance to stop it. Shortly before the decisive moment of action, Brezhnev was so afraid that he broke down crying and nearly bowed out of it:

“According to Moscow party boss Nikolai Egorychev, when Khrushchev told Mikoyan to investigate the evidence of a plot, Brezhnev started crying and said, “Kolya, Khrushchev knows everything. He will shoot all of us.” When Egorychev told him they were not violating any party rules, Brezhnev responded: “You don't know Khrushchev well.” Egorychev even had to take Brezhnev to a sink and tell him to clean himself up.”33

The internal politics and constellation of forces within Leninist regimes are vague even to those at the top. Khruschev, Torigian’s narrative argues, was overconfident in his position. Gorbachev, meanwhile, may have been paranoid. Hough writes in his book that “According to Ligachev, he [Gorbachev] seemed to have had a "Khrushchev complex," a memory of the removal of Khrushchev as party leader by the Central Committee in 1964 and an almost irrational fear that the same might happen to him.”

Ultimately, though, the presumption in Struggle that Khruschev’s upending of ministerial, agricultural, and industrial bureaucratic interests would reliably and inevitably produce a coup is unfounded. The case of the coup against comrade Khrushchev cannot serve as a load bearing pillar in the “helpless” narrative. Indeed, Gorbachev massively slashed and attacked the bureaucracy for years and faced no coup until August 19, 1991. And even then the plotters apparently intervened for a different reason (because they perceived, correctly, that the new Union treaty Gorbachev was about to sign was suicidal).

One can make arguments about Gorbachev’s psychology and its impact on policy while realizing that his views do not necessarily reflect reality. If anything, the structural realities of Leninist political systems provide an asymmetric array of tools to the leader over and against coup plotters (only the General Secretary, for instance, is formally empowered to engage in comprehensive institutional coordination).34 At the very least, the claim in Struggle that Gorbachev “could have easily been forced out, retired, jailed, perhaps even shot” is more reflective of Gorbachev’s statements (perhaps genuine beliefs) than a true fact about politics in the late Soviet Union’s Leninist system—or in any Leninist system.

Economic Reforms: Blocked or Botched?

The real politics in Leninist regimes happens inside the system. As Stephen Kotkin’s book Uncivil Society argued, when it comes to the Soviet Union and its satellites, scholars looking for the collapse via recourse to civil society were under sway of a false consciousness. The really core and interesting dynamics happened inside the all-encompassing regimes; that is, within “uncivil society.”35 If we want to understand the economic reform process (and ultimately the political reform process), Miller’s focus in Struggle is well-placed: we need to look at the complex constellation of bureaucratic forces and interest groups within the regime. The action is largely concealed, but nonetheless crucial to the determinants of policy.36

Some have noted their hope that revelations about the role of entrenched interests in blocking reform, as recounted in Struggle, may hold lessons for China analysis today.37 Indeed, entrenched bureaucratic interests (“vested” interests is the preferred term among China-focused analysts) are today often invoked as key impediments to productive reforms in China.38 Unfortunately Struggle does not seem to get the history right, and relying on it may mislead more than inform. Let’s see why.

In one review of Struggle, Oscar Sanchez-Sibony, a historian of the Soviet economy, acknowledges that “a fully built, industrial environment requires governance, and opaque, authoritarian governance has often managed to entrench obdurate interest groups.”39 But, he goes on, the bureaucratic politics and entrenched interest analysis in Struggle is

“rendered fallow by a lack of concern in investigating and documenting the reality of the society’s political economy…The linchpin of the argument is the existence of what Miller calls lobby groups in the Soviet Union. It is these, rather than Gorbachev, that the book makes accountable for the collapse of the Soviet Union. Their power and intransigence made reform impossible, Miller argues. Given the book’s reliance on memoir literature and published Politburo transcripts—that is, on the voices of Gorbachev and his team—this is perhaps no great surprise.”40

There is a presumed, but not well evidenced, bureaucratic hostility to reform, and a lack of scrutiny given to delineating the bureaucratic entrenched interests it argues blocked reform. Struggle, Sanchez-Sibony notes, provides precious little information on the contours of the entrenched interest groups identified:

“Miller speaks of three lobby groups in particular: the military-industrial complex, the collective farm lobby, and the energy industry. These entities, however, remain thoroughly impenetrable. The study does not succeed in illuminating what these lobbies are and how they function with any kind of evidentiary concreteness.”41

Staggeringly, the only evidentiary support offered in Struggle for why it takes military, agriculture, and energy as coherent anti-reform complexes is a single endnote that directs the reader to an essay in the 1998 book The Destruction of the Soviet Economic System.42 Sergei Guriev, another Soviet scholar, calls out this questionable and unsubstantiated categorization of anti-reform complexes in his review of Struggle:

“even if one accepts Miller’s political economy argument, it is not immediately clear whether his categorization of interest groups is correct. Why and how does he arrive at the “unholy trinity” of TEK, OPK, and APK [energy-, defense-, and agro-industrial complexes]? Miller describes the size of OPK (pp. 59–60), but not of the other two— and not of other potential lobbies. Given the centrality of the TEK–OPK–APK story to the book’s argument, it is striking that the justification of the choice of the three as the main powerful antireform lobbies is based on a single reference to page 157 in a book edited by Ellman and Kontorovich (1998). The latter is a compilation of essays of 1990s reform insiders. Page 157 is a part of Yevgeny Yassin’s essay, … [but it also] does not justify the choice of the three “powerful blocs.” Nor is this choice discussed in other essays in the book.”43

Vladislav Zubok, in his review of Struggle, highlights the same problems of unsubstantiated imputation of motives, lack of archival evidence, and a missing delineation of the contours of the USSR’s entrenched interest groups:

“The concept of ‘entrenched elites’ occupies a central role in the book. These groups, ranging from the agrarian collective farms’ lobby to the military-industrial complex, are presented as the main culprits of the excessive monetary demands, the inflationary pressures on the budget, and ultimately the political gridlock that destroyed Soviet finances and the economy. People in these groups, Miller tells us, were purely reactionary, anti-reform, and anti-market. Gorbachev was a captive of entrenched elites rather than a bold, determined reformer. The book presents him as “far weaker than nearly anyone realized,” because of “political forces that obstructed Gorbachev at every turn.” (9). This is where my dissatisfaction with Miller’s book begins. It starts with sources. The claim about entrenched elites requires ample empirical confirmation. And at a minimum one expects background information on the abovementioned groups and the nature of their obstruction of Gorbachev’s reforms. Yet the book does not provide such information. Miller seems to take the opposition to Gorbachev for granted, as if taking a leaf from the anti-bureaucratic perestroika rhetoric, and from statements by Gorbachev, radical economists, and the ‘democratic’ opposition.”44

Little archival evidence is presented in favor of the “helpless” narrative, despite claims that it does. Sanchez-Sibony goes on to contend that a “nod and wink” argumentation style in Struggle substitutes for evidence:

“In Miller’s description of how lobbying works in the “energy industry,” the logic seems to be that because Nikolai Baibakov had been oil minister and identified himself with that industry well into his old age, he systematically privileged it in his all-powerful role as Gosplan chairman. Rather than proving the case, the argument is made through a wink of complicity: “Is it any surprise that, as head of Gosplan, Baibakov looked kindly upon requests for more investment in the energy sector?” we are asked. This, however, runs against the headwinds of Douglas Rogers’s prizewinning book on Russian oil, which shows that, far from a coherent industry able to develop lobbying power, what Miller denominates as “the energy industry” was a fragmented set of managerial bureaucracies surprisingly inconsequential to domestic and regional politics…Although the energy industry and its man Baibakov serve the book as the general example for how lobbying might work, the individual cases end up focusing on enterprise and agricultural reforms, but with no particular evidence other than exasperated commentary from Gorbachev and his team that blocking these were coherent antireform lobbies.”45

The “wink and nod” reasoning is deployed in discussion of agricultural reforms, or rather the lack thereof. Struggle suggests condemnation of Gorbachev for failing to begin his reform process with agriculture is off the mark. He served as secretary in charge of agriculture prior to his ascension, his wife wrote a dissertation on collective farms, his family was negatively impacted by them. Of course he would be aware of and want to address the core problems, right?46 Such reasoning could be correct, but could just as well be told in a way that leads one to conclude that Gorbachev was himself an entrenched interest for collectivized agriculture. That line of inquiry is not pursued.

Meanwhile, much as Sanchez-Sibony calls into question the coherence of a singular energy “complex,” Jerry Hough warned decades ago that speaking of a coherent Soviet military-industrial complex made only limited sense, as the ministries in charge of producing materiel faced quite different, and often conflicting, incentives from the military itself.47 Delineating entrenched interests groups is difficult and, at minimum, requires attention to the differing incentives at play.

All of these critiques ultimately mirror what Hough had already written in his 1997 book Democratization and Revolution. Namely, that the “helpless” type narrative advanced in Struggle was ridden with “old assumptions about Soviet bureaucrats [that] have become part of the historical conventional wisdom.”48 Hough suggests a more accurate view might actually be the inverse: that “as soon as the bureaucrats and the nomenklatura became confident that economic reform was possible, they understood how they could benefit and they supported it.”49 That roughly 80% of private companies in 1993 were run by former Party-state managerial personnel in what some have called “the revolution of the deputies,” provides support for this.50 Zubok’s own assessment of the evidence is in alignment with Hough’s:

“It is hard for me to find in the records of Politburo discussions exactly which of the Politburo members provided, as Miller claims, “fierce opposition” to Gorbachev’s reform initiatives, and where these records appear…There is plenty of evidence that Gorbachev’s reforms initially evoked considerable support among a great number of Soviet factory directors (Prime Minister Nikolai Ryzhkov, Gorbachev’s supporter in 1985-1990, was one of them), and from the party-economic managers (partiino-khoziaistvennyi apparat) in many regions and localities.”

The fragmented authority narrative may actually be a more apt descriptor of the limited power of any given bureaucratic group, rather than of the power of the General Secretary. Entrenched interests within Soviet uncivil society—even if they were unified—would have faced a massive collective action problem. But bureaucrat groups were far from unified. As Kotkin wrote in Uncivil Society terms like “red bourgeoisie” or “new class,” which conveyed a sort of collective group consciousness and interest,

“went out of fashion long ago. Its power [that of the term “new class”] consisted in wielding Marxism against Marxist regimes, but, as Djilas himself later conceded, that was also its limitation. Far from acting coherently, let alone out of class consciousness, the Communist establishments were often incoherent, riven by turf wars and hyper secrecy.”51

As with China today, one must be conscientious and skeptical when it comes to analyzing the dark and murky world of entrenched interests and internal Leninist bureaucratic politics.

Reconsidering the Contours of the USSR’s Bureaucratic and Interest Group Politics

A more fulsome exploration of bureaucratic politics within the Soviet Union’s “uncivil society” is found in Hough (1997). He identifies three critical cleavages: (1) between economic sectors, most notably between the highly favored heavy industry and those in professions and the service sector52; (2) within the bureaucracy along generational lines, e.g., between status-hungry yet more liberal youth (Shestydesiatnyky or sixtiers, born between 1925-45, who ascended during the Khruschev thaw) vs. older conservatives pushed up under Stalin53; (3) and between the ministerial officials in Moscow and the Party officials in the provinces.

One can refine the cleavages even more. For example, within the state’s ministerial chain of command, those at the top and those at the bottom were mutually dissatisfied with the massive layer in between. Hough recounts the analysis of Tatiana Zaslavskaia in 1985, a sociologist typically associated with radical reform. She argued:

“the real structure of bureaucratic power was very different from the formal structure. State officials, she believed, were divided among three groups: those at the highest levels of government; those in the middle, "the employees of the branch ministries and departments and their territorial administrations"; and "the employees of the enterprises." The problem in the Soviet Union was not a concentration of power at the top, but "the clear overgrowth (gipertrofiia) of the intermediate link and the relative weakness of the lower and often the higher links." Economic reform, she said, "raises the prestige and influence of the first and third level, and lowers that of the second."54

The bureaucratic politics in the USSR were complicated but exploitable in a way the “helpless” narrative never explores. As Hough puts it: “Any scholar who had studied the provincial party secretaries knew they hated the ministries and Gosplan; they would support a leader who attacked the power of these Moscow institutions.”55 Indeed, “the party apparatus was not unified…the regional party organs are often divided among themselves and within themselves, [and] they agree on only one thing: they hate the ministries in Moscow.”56

This situation was amenable to a classic pinscher movement: where the top goes around the middle and aligns with the bottom. This, as Mark Lupher laid out in his book Power Restructuring in China and Russia, is precisely how multiple revolutionaries and reformers in both China and the USSR have gone about their power restructurings. And, in fact, this appeared to describe much of the logic of Gorbachev’s reform and restructuring.

The above overview just scratches the surface but hopefully offers a hint at alternative contours within the bureaucracy and bureaucratic politics (see Appendix 1 for a deeper overview of and cut into the USSR’s bureaucratic structure).

Reformable or No? The Core Divide

The most important and comprehensive bureaucratic divide—yet one that is controversial among Soviet analysts—was that between the ministries and the party apparatus. It is controversial because one’s assessment here—i.e., whether one thinks the party is divisible from the ministerial state apparatus—has very direct implications for how one views the USSR’s reformability, and thus the Soviet ability to follow the Chinese path of “market Leninism.”57 In the USSR’s administrative-command economy, the state ministries formally ran the “planned economy,” so in theory the Party could have persisted largely intact while overseeing a major diminution of the ministries’ role and a transition to the market—i.e., followed China’s path. This divide runs through the “helpless” and the “reckless” narratives.

In Struggle, Miller concludes the Party was compromised beyond hope:

“By the time Gorbachev came to power…there was no way out. The Soviet system gave power to a new ruling class: generals, collective farm managers, and industrial bosses, all of whom benefitted from waste and inefficiency. They dominated the Communist Party and hijacked its policymaking process, so that by the 1980s, there was no longer a boundary between industrial lobbies and the Communist Party itself. The political clout of these interest groups proved far more significant than anyone expected. Gorbachev’s legacy—and the entirety of Soviet history during the perestroika period—cannot be understood without a clear view of the vicious infighting that determined which policies were implemented and which were discarded.”58

But Hough in Democratization and Revolution thought this was not the case:

“the Communist party is the only institution with the power to challenge the ministries. In much of the Western literature, this fact has been taken to mean that reform is impossible. Party officials are often described as an especially conservative and ideological group who are counterpoised to a more reform-minded, pragmatic group in the governmental machinery. In reality, the traditional Western interpretation should be reversed. The Central Committee apparatus, headed by the Central Committee secretaries, has some fifteen hundred officials, who are directly supervised by the general secretary and have a special relationship to him. Moreover, many of these officials do not have a power comparable to that of the ministries and develop a resentment toward them… Not surprisingly, almost every article published by the provincial party secretaries for thirty years has contained complaints about the ministries and the State Planning Committee. If "their" general secretary calls for the support of the provincial first secretaries in an attack on the ministries, their sheer pleasure will overshadow any lingering doubt about their own self-interest.”59

My guess: Hough is right, it was possible to deconstruct most of the ministerial system and much of the planned economy without deconstructing the party. In fact, the party may have been necessary in this process (more on this at the end). But that was not the path Gorbachev chose to pursue.

A Revolution from Above… and Below

Gorbachev routinely referred to perestroika as a “revolution.” This was perhaps the most prominent theme of his 1987 book Perestroika, which he took the time to produce for a Western readership smack in the middle of his reform process. “Perestroika,” Gorbachev wrote, “is a word with many meanings. But if we are to choose from its many possible synonyms the key one which expresses its essence most accurately, then we can say thus: perestroika is a revolution.”60 He argues “it is precisely measures of a revolutionary character that are necessary for overcoming a crisis or pre-crisis situation.”61

While his bureaucratic and personnel changes focused on increasing his own power, many of his key economic reforms—most importantly the 1987 Law on State Enterprises62—were in fact centered on devolving power downward. Economic reform was, in Gorbachev’s understanding, about making socialism work. In his own words, “Perestroika…means the combination of the achievements of the scientific and technological revolution with a planned economy.”63 Gorbachev’s crude, changing, and often contradictory vision was of unleashing bottom-up enthusiasm to implement technological advance while maintaining core aspects of a planned economy. If that sounds terribly confused, that is because it was. In a passage from his 1996 memoirs that is both revealing and believable, Gorbachev himself admits as much:

“Independent specialists believed that the basic reason for the country's backwardness was that we had missed a new stage in the scientific and technological revolution, while the Western countries had moved far ahead both in restructuring their economies and in technological progress. The problem did not lie only in errors or in undervaluing science and technology, but rather in the archaic nature of our economic mechanisms, in the rigid centralization of administration, in over-reliance on planning and in the lack of genuine economic incentives. However, the recognition of the need to improve the economic mechanism did not go beyond the formula of 'more complete use of the potentialities of the socialist system'… For some time we indeed hoped to overcome stagnation by relying on such 'advantages of Socialism' as planned mobilization of reserve capacities, organizational work, and evoking conscientiousness and a more active attitude from the workers…The fact was that the extremely alarming economic situation that we had inherited required immediate measures. We felt that we could fix things, pull ourselves out of this hole by the old methods, and then begin significant reforms. This was probably a mistake that wasted time, but that was our thinking then… While I was aware of the importance of economic reforms, I also believed that it was first necessary to try to modernize the economy so as to set up conditions for radical economic reform by the early 1990s. This was the aim of the all-Union conference on scientific and technological progress. I note for clarity that these ideas were similar to Deng Xiaoping's reform methods in China.”64

Properly utilizing incentives and carefully reconstructing institutional mechanisms, as Gorbachev himself admits, often took a backseat to vacuous sloganeering, which appeared to serve as a stopgap in thinking. Gorbachev repeated ad infinitum that he sought to activate the “human element,” unleashing the latent “potentialities of socialism,” fully realize the so-called “advantages of Socialism,” and on and on. Socialism and democracy were inseparably bound, in Gorbachev’s view—a formula he would also repeat ad nauseum. This all seemed to reflect a hope that mobilizing the bottom up spirit of Soviet citizens and workers would be, if not a panacea, at least a route to Pareto improvements.

Such preoccupations with mobilizing a revolutionary human spirit are something of a common pattern among Marxist-Leninists. “Khruschev,” for example, “railed against Soviet scientists for failure to understand the latent potential of the masses.” In China, not wanting to be outdone, “Mao complained that the Soviets underrated the power of the human spirit.”65 Gorbachev was infected with something of the same strain. A belief in the power of the human spirit. A disregard for material incentives. A lingering faith in the ability to leap to a kingdom of freedom in a single bound.

One consequence of the strain that infected Gorbachev, however, was an anti-bureaucratism that sought to make good on something like Marx’s withering away of the state. Indeed, Gorbachev blamed the bureaucracy—not unjustly, of course—for squashing popular enthusiasm. He wrote in 1987 that the USSR was beset by and subject to “bureaucracy-ridden public structures and to expansion at every level of bureaucracy. And this bureaucracy acquired too great an influence in all state, administrative and even public affairs.”66 As a result, “little room was left for Lenin's idea of the working people's self-management.”67 He publicly deployed rhetorical fire to match and encouraged Yakovlev and those who controlled state media—as well as emerging free voices in glasnost—to critique the bureaucrats as much as possible. Miller notes this, quoting Gorbachev and adding his own flair:

“Gorbachev argued, the government and the party should openly support individual workers against tyrannical bureaucrats. “In communication about this meeting of the Politburo, let’s make clear what has been said. And Afanasiev [editor of the newspaper Pravda] and Skliarov [of the Propaganda Department] should make use of all methods— press, radio—to debunk local bosses, local bureaucrats, who squeeze individual activity.”68

Gorbachev was explicitly aiming for that classic pinscher movement of the top (i.e., himself) and lower stratums against the middle, as he himself wrote: “It is a distinctive feature and strength of perestroika that it is simultaneously a revolution "from above" and "from below."”69

For Gorbachev then, consolidation of power was for a purpose: to mobilize bottom up enthusiasm and unleash the latent potentialities of socialism that were being bureaucratically stifled.

It was Gorbachev’s own beliefs about how perestroika would work—the importance of empowering the people against the bureaucracy—that deterred him from critical reforms, most importantly price reform, and thereby undermined the program’s overall efficacy.70

Reforms: Botched, Not Blocked.

The Soviet economic system had an emergent logic at the intersection of planning, party intervention, and an underground market economy (see Appendix 1). There is no doubt that there were many entrenched interests that were resistant to certain reforms, and there is no doubt that Gorbachev faced a massively complex challenge in fundamentally fixing the USSR’s economic problems. The bureaucracy was pervasive, and the array of interests and incentives propelling its behavior bewildering. It is certainly not out of the question that the system was unreformable.

But rather than a well-considered reform—involving a meticulous understanding of institutions and incentives, axing where appropriate, and using a scalpel otherwise—a solipsistic revolutionary approach was pursued (particularly after 1988). One reviewer of Hough’s summarizes this view well:

“For Hough…Gorbachev is both a shrewd political operator, putting himself in power through the adroit use of patronage politics and Kremlin maneuvering, and at the same time staggeringly naive about the importance of institutions to managing a modern state and economy… Rather than carefully thinking through the institutional requirements of transition, Gorbachev simply torched existing institutions of party and state in the hope that a new Soviet society would rise from the ashes… Behind this neglect of institutions lay a streak of anarchism. Gorbachev, like Yeltsin, "came to accept Karl Marx's assumption that the state does not play a crucial or even useful role in economic performance, that it is parasitic and that planning can be achieved as it withers away" (p. 2). This, combined with an irrational fear of the power of the Soviet bureaucracy, made Gorbachev demolish the power of the state in a misguided attempt to thereby revitalize a stagnant system.”71

If this view is correct, one lesson for those seeking to understand reforms in China today is that the leader, his competence, and his perceptions of how to enact reform can, at times, prove even more important than the underlying realities of bureaucratic politics or structural issues.

In this view, the key questions become:

· What problems does the leader perceive in the current system?

· What types of reforms does the leader think will fix those problems?

· Who or what does the leader think stands in his way?

· What are his strategy and tactics for implementing those reforms and getting around entrenched interests, road blocks, and obstructions?

An objective, first order analysis may help analysts determine whether or not the leader’s diagnosis is correct and whether or not his reform approach is likely to be efficacious. But one should not be confused into thinking that there is no gap between reality and perception. Leaders can always misdiagnose problems, or respond to real problems in less than optimal ways.

A quick look at two of the most pivotal reform issues in the USSR will help to show that this is in fact what happened under Gorbachev, that the “helpless” and “stymied” narrative falls short, and that a “botched” narrative seems to make more sense.

The Case of the Missing Price Reform

Of the many reforms on the table under Gorbachev, arguably none was more crucial than price reform. While others, like the Law on State Enterprises (1987) and the Law on Cooperatives (1988) that sought to increase bottom-up autonomy and initiative were very important, without price reform they would not work properly.72

Without prices that better reflected supply and demand, enterprises remained trapped within the confines of the administrative-command system and unable to act autonomously and spontaneously.73 This was so not because of bureaucratic resistance or the desires of entrenched interests, but because the critical reform enabling transition out of an administrative-command system never came. Lacking this basic ingredient of functional autonomy, how could enterprises stay alert and adapt to changing circumstances, fund capacity expansion, take costly risks on technological upgrading and quality improvement?

Hardly any price reform occurred prior to 1991, by which time the Union was being torn asunder due to the consequences of Gorbachev’s political reforms, and there were far bigger issues to contend with.74 It was a core failing of perestroika, as agreed upon by multiple insiders in their contributions to Ellman’s (1998) Destruction of the Soviet Economic System. In their memoirs, many of the highest leaders also agreed not pursuing price reform earlier was a mistake—including Gorbachev!

How does Struggle narrative deal with this failure? While it demonstrates quite well that Gorbachev understood the central significance of price reform, it also shows that he was paralyzed by his idiosyncratic—and ultimately self-harming—belief that it would undermine the mass enthusiasm he deemed even more important to the success of perestroika. But Struggle tortures this fairly self-evident explanation into compliance with its “helpless” narrative. An extended quote is needed to do the contortion justice:

“As Gorbachev told the Politburo in May 1987, “the question about prices is principle, fundamental. If it’s not solved, there won’t be self-accounting for enterprises, nor self-financing, and perestroika will not work. But you know how hard it is to start a new policy [perestroika] with price increases!” … The Politburo and Council of Ministers regularly discussed price increases during 1987 and 1988. Yet Gorbachev was deathly afraid of the political consequences… Gorbachev advocated price revisions in principle, but never proposed a concrete policy. “On the subject of price controls. If we don’t come to an agreement, it means that we’re afraid,” he argued. But he was afraid, and sensibly so. Gorbachev realized, as he explained to the Politburo, that if prices do not “correspond with reality, we won’t have any mechanism of economic governance. But most importantly: changes in prices shouldn’t undermine the standards of living of the population, or economic development at the present time.”75 … “But Gorbachev believed, probably correctly, that raising prices was politically impossible. “Some people are demanding price increases,” he [Gorbachev] said. “We won’t do that. The people have not yet received anything from perestroika. They haven’t felt it materially. And if we raised prices, you can imagine the political results: we would discredit perestroika.” Discrediting perestroika meant discrediting himself. It also meant empowering those among the Soviet leadership who opposed any economic reform. Gorbachev was unwilling to take that risk. Soviet leaders remembered the riots in the southern city of Novocherkassk after the price increases of 1962. Gorbachev knew that a similar revolt could easily cause his opponents to oust him.”76…“This was the basic dilemma: raising prices to approximate free market levels would help resolve the country’s growing economic problems, but price hikes were opposed by many in the Politburo. Even if Gorbachev had been able to push through price increases over his opponents’ objections, the public backlash against higher prices would give Gorbachev’s rivals a propaganda coup and let them derail perestroika... “Increase prices?” he asked at one Politburo meeting. “That means social tensions, threatening perestroika.” The opposition was just too strong, Gorbachev believed, to ram through price increases.”77

This interpretation of Gorbachev’s own quotes seems to stray from their face-value meaning. Gorbachev is quite literally saying he will not do price reform because he does not want to impose costs upon people before the imagined benefits of perestroika arrive (i.e., Pareto improvements from achieving the potentialities of socialism). Rooting Gorbachev’s actions in fear of entrenched bureaucratic interests and hostile elite co-conspirators is simply a tortured telling of this story that strays from face-value.

The narrative in Struggle is not even particularly consistent with Gorbachev’s post-hoc account. Indeed, Gorbachev’s own post-mortem on the price issue, written a decade later, seems to directly contradict it. Gorbachev seems to lament the fact he did not simply force it through: “We had allowed the most favorable period for this (1988-90) to slip through our hands.”78 Gorbachev then expounds upon this in his Memoirs, heaping blame upon the populists and radical democrats that he himself had unleashed—not upon supposedly powerful and recalcitrant entrenched elites or bureaucratic resistance:

“it was obvious that, with time, the conditions for major price reform would only deteriorate. However, those in the government [as if he were not in charge…] were afraid to tackle this highly sensitive issue. Thus we lost several months in senseless bureaucratic wrangling. Meanwhile, rumors of an attack on stable prices trickled through society and caused growing alarm. This issue was eventually picked up by populists and politicized. In spite of many assurances that the revenue from price increases would be returned to the people (primarily to low-paid workers through wage increases) and that the decision on prices would not be made without discussing it with the people, a noisy campaign against price reform being counter to the interests of the people was carried on in the press. “'Hands off prices!' was the first slogan of the emerging radical democratic opposition. They were not at all bothered by the fact that this attitude blocked economic reform and that they themselves could not avoid taking this action if they came into power. As in many other instances, the interests of the nation were sacrificed to the desire to win cheap popularity. Radical newspapers published letters and wrathful diatribes, and in only a few weeks public opinion changed to total rejection of price reform.”79

But memoirs are often unreliable sources, as we know. Hough, therefore, contends that Gorbachev’s Memoirs are more than a little bit self-serving in their framing the issue of the missing price reform. It was, in Hough’s view, neither entrenched interests nor democratic opposition: it was Gorbachev. Had Gorbachev been decisively in favor of price reforms, or even just fiscally responsible increases, he almost certainly could have gotten his way. Far from being hemmed in by others, and far from “those in the government” stalling on the issue of price reform, it was Gorbachev himself who continuously prevaricated or actively intervened against. Many on the politburo were supportive.80 Most important was premier Nikolai Ryzhkov—something of an unheralded hero for Hough—who pushed for strong retail price increases to better reflect actual supply and demand, if not yet full price reform (i.e., ending administrative price setting).81 But Gorbachev intervened decisively at key movement to prevent retail price hikes, not out of fear of entrenched interests, but because he had a particular belief about how reform should work: the people, as Struggle itself quotes Gorbachev saying, should first see benefits from perestroika before the pain of price increases, lest mobilization of the “human factor” be dampened. Unfortunately, those benefits never came, nor did price reform.

On the critical issue of the missing price reform, not even Gorbachev is as sympathetic to Gorbachev as Miller is in Struggle. The “helpless” narrative of Gorbachev cowed by fiercely powerful entrenched interests seems largely foreign to what actually transpired.82

Blowing out the Budget: Who Done It?

In 1985, when Gorbachev took over, the budget was nearly balanced, as the Soviets defined it. Within a few short years the budget deficit ballooned and by 1989 it was, seemingly overnight, 90 billion rubles, or 10 percent of Soviet gross national product.83 As Gur Ofer noted in 1989, by this time “the leadership and economists in the Soviet Union regard[ed] the fiscal crisis as the country's most acutely pressing economic problem, not only because of its effect on the current economic situation, but also because many critical elements of the reforms depend[ed] on establishing a solid fiscal and monetary infrastructure.”84

We are told in Struggle that it was entrenched interests and their “demands for handouts [that] tore a hole in the Soviet budget.” Gorbachev, as usual, “lacked the power to resist.” This in turn meant “Chinese-style authoritarian politics could never have supported Soviet economic reform, because the most reactionary institutions—above all, the military—were the most opposed to the measures needed to stabilize the economy.”85

Yet while the military was undoubtedly bloated beyond any reasonable size given the USSR’s underlying capacity, Gur Ofer, one of the foremost experts on Soviet budget data, noted by the late 1980s it was “generally agreed that defense budgets have been going down and can decline further.”86 Estimates were that defense spending was somewhere around 10-15 of Soviet GNP, though it is still heavily debated.87

So was it really entrenched interests that “tore a hole in the budget”?

Revenue barely increased under Gorbachev’s tenure. Yet this was not the doing of entrenched interests—at least not of the sort Struggle has in mind. It was rather due mostly to Gorbachev’s own policies: (1) to allow enterprises more autonomy and to keep more of what they earned (Law on State Enterprises); (2) refusal to increase retail prices; (3) anti-alcohol campaign; (4) as well as a collapse in global commodity prices (not, of course, Gorbachev’s fault).

Profit transfer from enterprises to the budget, point (1), was “the single most important source of tax revenue” but was “lower in 1989 than in 1986, owing mainly to the economic reform provision that permitted enterprises to keep a much larger share of their profits in order to finance their own investments.” An intended result of the Law on State Enterprise.

The second most important revenue source, point (2), was the turnover tax—the amount the state adds on between the wholesale and retail sale price and takes for itself. Turnover tax revenue barely budged from 1984 to 1989.88 We have already seen Gorbachev refused nearly all fiscally responsible price increases or reforms.

The anti-alcohol campaign (3) and the fall in commodity prices (4) each had a roughly equivalent negative impact on the budget. Revenue from alcohol sales had made up roughly 12-13 percent of budget revenue in 1982, and was down at least 25 percent by 1986.89 Miller cites Finance Minister Boris Gostev as saying, in 1987, that “losses due to falling oil prices on the world market were 15 billion. From [falling sales of] vodka—also 15 billion.”90 Combined these two hits to Soviet revenue account for perhaps a third of the 90 billion deficit.

Expenditures, meanwhile, increased sharply. The main spending areas were the following: (1) The industrial modernization program, (2) planned losses of enterprises, (3) rising subsidies on food and other consumer related items, (4) expansion of welfare programs, and (5) defense outlays.91

Points (1) and (2) are similarly direct consequences of Gorbachev’s actions. Planned losses are related to the 1987 law, and acceleration to Gorbachev’s self-admitted move to make good on the scientific technological revolution via the “old methods,” as discussed earlier.92

Yet Struggle seeks to explain away Gorbachev’s “acceleration.” Allegedly, Gorbachev got the Law on State Enterprises only by placating entrenched interests with increased capital spending. 93 But there is no evidence this was a quid pro quo, nor that Gorbachev thought this way. As Yakov Feygin suggests a rather more convincing argument, that Gorbachev was earnestly trying to make good on the scientific and technology revolution his predecessors had promised.94 Gorbachev, as we saw, says as much in his Memoirs (attributing acceleration to a mistaken belief in the old ways).

Points (3) and (4) further conflict with the bureaucratic entrenched interest explanation. Gorbachev himself refused to raise retail prices, but did increase the wholesale price for grain—not because the “agriculture complex” forced him to, but more because urban citizens’ were complaining about meat consumption levels, while the USSR was so short on grain that it needed to import agricultural product to feed livestock. The pricing system under Gorbachev remained so irrational that it was cheaper for farmers to buy finished bread to feed their farm animals than it was to purchase their own grain.

Urban consumer subsidies were far larger and more devastating to the budget than just about anything else. Gorbachev and the regime, which still maintained its household registration system limiting internal migration, nurtured a massive urban consumer bias. It was Gorbachev’s revenue cuts combined with an unwillingness to impinge upon this broad group that exploded the budget deficit, not the complexes of entrenched interests pointed to in Struggle. In fact, Gorbachev massively expanded subsidies to them. Social expenditures stayed below 20 percent of Soviet GNP until 1980. But “then the economic growth came to an end and the fulfilment of the social contract obligations resulted in a rapid increase in the relative volume of social expenditures: their ratio to GNP increased from 20.7 percent in 1980 to 25.4 percent in 1985, 30.2 percent in 1990 and 33.9 percent in 1991.”95 Thus the biggest budgetary problem may have been that decades of rhetoric about a proletarian workers paradise actually had an impact.

The USSR was a welfare state of a peculiar sort. Most of the increase came via urban consumer price subsidies: “The greatest growth was in price subsidies. In absolute terms, they increased six-fold during 1976-1990, and their share in total [social] expenditures (including hidden budget outlays on subsidies) increased from 19 percent to 44 percent during the same period.” More broadly, “the ratio of consumer subsidies to GNP increased from 4 - 5 percent in 1976-1980 to 13 percent in 1990. This was the price paid for the social illusion of low and stable consumer prices.”96 No other portion of the budget increased anywhere near as fast.

Structure of Expenditures in the Soviet Budget

The USSR had become a welfare state of a peculiar sort, mostly via subsidization of benefitting relatively well-off urbanites, as Hough had correctly noted.97 Highly desired and promised staple foods like butter, milk, beef, and pork.98 If “powerful interest groups obstructed Gorbachev’s policies,” as Miller contends, it was not principally the bureaucratic complexes he points to in Struggle.99 Rather it was the broad interests of a heavily subsidized urban populous. He gets quite close to making this point in Struggle, but then backs off in favor of a return to the helpless narrative:

“Soviet leaders knew that government programs to subsidize food and other consumer prices constituted a multi-billion ruble annual spending program, eating up 10 percent of the USSR’s GDP. Food subsidies were by far the largest component of the Soviet welfare state, dwarfing spending on pensions or education, for ex- ample. Through subsidized prices, the government paid nearly one-third of the cost of every loaf of bread that was purchased, over half the cost of every gallon of milk, two thirds of the cost of butter, and a whopping 72 percent of every kilogram of beef. The main beneficiaries of this spending were not the poor, but the wealthy. Slashing consumer subsidies would have resolved the Soviet budget crisis. It would have reduced, Finance Minister Gostev noted, expenditure levels by 100 billion rubles per year by the end of the 1980s. But Gorbachev believed, probably correctly, that raising prices was politically impossible.”100

Instead Struggle goes on:

“Gorbachev was left with a terrible dilemma. The budget could not be balanced. Raising consumer prices would have been politically fatal, resulting in Gorbachev’s political marginalization, if not complete removal from power. That would have frozen efforts to liberalize industry and agriculture. At the same time, Gorbachev lacked the political influence to reduce spending on the parts of Soviet society most able to absorb cuts—the USSR’s massive military- industrial complex, its bloated industrial ministries, or its perennially inefficient agriculture sector. Reducing these groups’ subsidies was so politically untenable that it was not seriously discussed.”101… “The immense power of economic interest groups in Soviet politics severely limited the number of policy choices that were realistically possible. Balancing the budget with tax increases, spending cuts, or price increases would have been politically devastating.”102

Entrenched interests did not tear a hole in the budget, it was a consequence of botched reforms.103 Philip Hanson, in his The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Economy, cites a contemporaneous CIA overview approvingly, when he concludes that “in short, it was Gorbachevian policies, for the most part, that created the problem.”104

Miller acknowledges at multiple points that what Gorbachev was doing was a gamble, but says he had no choice—he had to print money, he had to do what he did—he was “helpless.” But that is wrong. Gorbachev’s gambles were not necessary, they were “reckless.”

The Soviet budget then spiraled from crisis in the late 1980s into fully blown catastrophe in 1990 as new, democratically elected Republican-level parliaments came into existence and absolute chaos in the budgeting process was introduced. Most importantly, the new Russian legislature under Boris Yeltsin fought doggedly with the Union for control over the budget, over tax resources, and over control of enterprises. The budget for 1991 was barely even drawn up, but estimates of the deficit suggest it expanded from a massive 10% of GNP to a mind boggling 30% of GNP.

It is unfortunate that the “helpless” narrative advanced in Struggle, due its scope of focus, does not include discussion of the most spectacular change in the Soviet system under Gorbachev: the fact that there were genuine, democratic institutions in the USSR beginning in 1989/1990.

Let There Be Democracy! Avatar Mikhail Gorbachev: The Last Reformer Airbender

Gorbachev’s real revolution began in June 1988 when he convened a special Party Conference for the first time in nearly five decades.105 It was here Gorbachev began a rapid effort to intentionally undermine his existing base of institutional power, the Communist Party, and create a new institutional power base: a democratic “super parliament,” the Congress of People’s Deputies (CPD). The gathering of thousands of specially elected Party representatives served to legitimate the process Gorbachev was about to launch into. It was here that Gorbachev explicitly stated he was cutting “the umbilical cord tying [the party] to the command-administrative system” and earnestly began slashing the bureaucracy.106

The first CPD elections were held in March 1989, and its first meeting was May 1989. The national CPD elections were the closest thing to free, fair, and authentically democratic elections since the Constituent Assembly elections following the Bolshevik’s October coup in 1917.107 This development in the USSR cut a stark contrast with the martial law declared in China at the same moment. In fact, the Tiananmen massacre only deepened Gorbachev’s resolve to move faster and avoid the Chinese path of market Leninism.108

Yet much like the coercive Bolshevik dissolution of the Constituent Assembly in January 1918 spelled the beginning of the communist dictatorship, so the CPD’s convocation signalled the end of party control over the USSR. The electoral process stimulated all manner of nascent nationalisms. It brought together an emerging set of more educated, and more nationalistic, elite and showed them their common grievances. Unfortunately, as Stephen Kotkin noted of it: “Ultimately, the only unambiguous results of the elections, which were carried out against the astonishing deepening of glasnost, were to discredit the prevailing Soviet system of one-party rule and magnify the general disgust with all political authority.”109

In March 1990 Gorbachev got the new democratic super-legislature to amend the USSR’s constitution, formally removing Article 6 and thus renouncing the CPSU’s political monopoly and “leading role.” The party, it was decreed, was to stay out of the economy—a development that was seeded by Gorbachev’s massive bureaucratic downsizing and abolition of nearly all industrial departments, a restructuring mirrored at all levels of the Party bureaucracy.

Simultaneously, he got the CPD to create him a new position of peak power: the Presidency of the Soviet Union. And rather than campaign and face a popular election, the CPD internally elected him—a move some consider a critical error. Many in the democratic intelligentsia he was trying to court saw his new position as illegitimate.

The aim of all this, as Miller himself rightly noted, was to continue reforms without the party. Gorbachev was intentionally torching his communist party power base while trying to rapidly switch to a new base of executive authority rooted under the CPD. In practice, he seemed to evince a belief that the party could have little to no productive role in the reform process.110 As Stephen Cohen wrote in a retrospective:

“The election of a national parliament and the creation of Gorbachev’s executive presidency in 1989 and 1990 were turning points in Soviet history. They broke the Communist Party’s seven-decade monopoly on political life and thus fundamentally eroded the Leninist political system. Much that now ensued…was aftermath. The democratization process greatly outran Gorbachev’s economic reforms while generating popular protests against growing consumer shortages, rising inflation, and longstanding elite privileges. Even more destabilizing, the political change allowed nationalist discontent in several of the fifteen republics to develop into anti-Soviet movements for independence.”111

Gorbachev succeeded in undermining the institutional power of the party, as well as its remaining legitimacy, and its economic coordination function (i.e., picking up the pieces of a dysfunctional planning system).

The spiral into chaos already underway became truly catastrophic in March 1990, as the Union-level CPD was replicated at the Republican level and voting occurred in Russia. Boris Yeltsin resigned from the Union-level CPD to run in the Russian Republic CPD and won his seat in Moscow overwhelmingly (in what is widely considered a completely free and genuinely democratic election). In June 1990 the Russian CPD, in a highly contested internal election, then made him chairman over and above Gorbachev’s meek efforts to intercede. This spelled doom for the USSR.

On June 12, 1990 the Russian CPD under Yeltsin officially adopted the Declaration of State Sovereignty, declaring that its laws took precedence over Soviet laws, that it, not the USSR, was to take effective control over the many SOEs and industries within its territory, including the rights to enterprise profits / tax revenue.

The famous “war of laws” between the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) and the USSR quickly broke out—the real dagger in the heart of Gorbachev, the USSR, and the reform process. The Russian Republic, comprised 75 percent of the Soviet Union’s territory, 60 percent of its production, and 50 percent of its population. For the entirety of the Soviet period, the CPSU had denied Russia the right to establish its own communist party and central committee out of fear that an autonomous, empowered leadership group in the Russian Republic would have been uniquely equipped to undermine Soviet rule. This long-standing fear was rapidly validated.

Less than a year later in April 1991 the Russian CPD established a new post of Russian President, providing an even more autonomous center of power. In June 1991, in a free election based on direct popular vote, Yeltsin won resoundingly with 57 percent support (Ryzhkov, Gorbachev’s former premier, was next with 16.9 percent).

Russia was now sovereign, declaring its right to basically everything formerly controlled by the USSR, and had its own President in direct confrontation with the USSR and its President. The logic and control mechanisms of the existing system unraveled.

The conservative coup against Gorbachev in August 1991 was a last ditch measure that proved farcical. Yeltsin bolstered his populist democratic persona, furthering his image as media darling, by standing in front of the new Russian parliament in front of hostile military forces who never used any serious force. The fall out gave Yeltsin carte blanche to do as he wished.

Yeltsin immediately suspended all CPSU activities and then on November 6, 1991 issued a decree banning the Communist Party from Russian soil, dissolving its structures, prohibiting operations, and seizing its assets. Yeltsin finished what Gorbachev started. The Party was over.

Then he moved on to the USSR, which Gorbachev had intended to save with the new union treaty that would have been signed August 20th—devolving substantial fiscal and other authorities to the Republics—had the coup not prevented it. Instead, Yeltsin, with the heads of the Ukrainian and Belorussian Republics, simply declared the Soviet Union dissolved. Gorbachev’s power fully lost, he resigned on December 25th. The Gorbachev revolution was over.

This therefore was the mechanistic collapse of the Soviet Union—the proximate cause: Gorbachev’ intentional undermining and shifting of institutional power and the Russian secession it enabled under Yeltsin.

Gorbachev’s reforms began with the aim of resuscitating the Soviet economy. But instead they brought ruin, destroying the Soviet economy along with Soviet state capacity. This did not occur because Gorbachev was “helpless” and trapped by entrenched interests, but rather because he proved to be a well-intentioned reformer with great power that was used in a reckless manner.

Reforming From Weakness

Several events made Gorbachev’s political reform timing particularly disadvantageous: (1) an ongoing catastrophe of the Afghan War and extrication attempt (1981-1989); (2) the Chernobyl disaster and its fallout (1986); (3) commodity price tailwinds became headwinds 70s and early 80s turned into serious headwinds. As institutions crumbled, economic performance was going from bad to worse and multiple other crises were converging (a polycrisis, as they say).

Attempting a rapid transition from a closed, quasi-totalitarian, single party political system to a multi-party quasi-democratic system at a moment of acute challenge was a recipe for disaster. The historical record is littered with regimes who long delayed major reform only to seek salvation via radical reform in periods of weakness. Soviet reforms tragi-comically mirrored aspects of the collapse of the Ancien Regime in France and the Qing Dynasty in China. Both conceded radical institutional reforms, including creating a new “super parliament” representing a disgruntled elite stratum, in moments of economic and systemic crisis.

Newly empowered elites in the Soviet case may not have been able to cohere around or introduce a positive reform agenda for the economy, but they did seem to agree on a negative program: do away with the old system. It seems to be a truism that it is easier to cohere around and against a common evil than in favor of a common good. This is particularly true when there are so many justified grievances to go around–a failing economy, decades of political oppression, forceful subjugation of many far flung territories…the list goes on.

There was an element of the Tocquevillian paradox at work as well. Even as democratic concession after democratic concession was forthcoming, the mood was only growing more radical. The regime was less oppressive than ever yet each and every injustice that remained felt, with removal now conceivable, more and more unbearable.

Authoritarian regimes, according to Dan Slater and Joseph Wong’s From Development to Democracy, have the best chance of shifting to a stable democratic institutional set up when they do so voluntarily and from a position of strength, not weakness.112 Gorbachev’s radical effort to undermine the party and try to secure a more democratic basis of power was unlikely to work out well in a moment of acute and growing weakness.

Summing Up: The Suicidal Struggle to Save the Soviet Economy

“This radical revolution, which was to join together in one and the same destruction of both what was worst and what was best in the Ancien Regime, was unavoidable. A nation so poorly prepared to act independently could not attempt total reform without total destruction. An absolute monarch would have been a less dangerous innovator. For myself, I observe that this same revolution, while it destroyed so many institutions, ideas and habits opposed to liberty, on the other hand it abolished so many others that freedom could hardly do without. Then I am inclined to believe that, had it been achieved by a despot, it might perhaps have left us less incompetent to become one day a free nation than one effected in the name of the sovereignty of the people and by their own hand. We must never lose sight of the above if we wish to understand the history of our Revolution.”113

Structural political economy explanations, captivating as they are, seem incapable of taking us over the threshold of an explanation for what went wrong. Upon closer inspection one is forced back, as I was, kicking and screaming, to the Gorbachev factor.

The great man theory of history has gone out of fashion, yet there are moments where the acts of singular individuals determine the fate of nations. This is an inevitable risk in any large-scale, hierarchical human social arrangement. Captains can crash ships.

Gorbachev was a good man. In fact, some argue, and I agree, he was in many ways a heroic figure. As one sympathetic Russian who became involved in the Yeltsin administration put it: “Mikhail Gorbachev freed us — his contemporaries. . . . He liberated us. And he did this of his own volition. We didn’t even ask him. At the time only a miniscule number of people were fighting for freedom, while even fewer believed that this was actually possible. Gorbachev gave us all freedom. He is not to blame for what we did with this freedom.”114

Gorbachev’s good intentions are important but should not blind one to reality. As today with Xi Jinping, an analyst’s own unchecked moral or ideological dispositions can easily bias or undermine analysis. The same risk applies to historical analysis of Gorbachev and his reform efforts.

Certainly Gorbachev, was far from clueless about how power worked in the USSR. Yet he nonetheless came to adopt a conception about human agency and the importance of institutional state capacity that proved devastating. A strain of foolhardy idealism ignorant and/or dismissive of material and institutional incentives that appears quite strong in the lineage of Marxist-Leninist leaders.

Gorbachev was seeking Pareto improvements—reforms that would leave everyone better off—when there were no such improvements to be had. Lacking in understanding of economics, as he himself admits, he initially leaned on the old mechanisms of the administrative-command economy to achieve the “scientific technological revolution” and activate the “potentialities of socialism.” But Gorbachev quickly grew discouraged and soon reached for more ambitious reforms, the Law on State Enterprises and Law on Cooperatives, among others, that would devolve economic decision-making, empower and activate lower strata, while somehow also meshing into and sustaining a planned economy. Unfortunately, Gorbachev’s own confused priorities led him to reject critical changes—price reform—for far too long.115 Devolution of decision-making consequently took place in a wantonly irrational environment, and produced autonomous actors who simply made nonsensical and typically deleterious (though oft self-aggrandizing) choices.116

More importantly, Gorbachev pursued political reform at nearly the same time he began implementing more substantive economic changes. By 1989 economic reform took a backseat to political reform, and by mid-1990—little more than a year or two after the first substantive economic reform efforts took effect—evolutionary reform became effectively impossible as party-state capacity to mediate it was gone.117

In the economic domain, the situation prior to 1985 was inefficient but stable. A low-level equilibrium. “It cannot be emphasized too strongly,” Philip Hanson wrote, that economic chaos “was not the 'old Soviet system' failing but the old Soviet system being abandoned. It was the product of a collapse of the rules of the economic game and of economic warfare between the Soviet republics and the Union.”118