Financialization: Is it Worse in the PRC?

Over at Scholar’s Stage there’s a very good post with the mildly hyperbolic title: ‘Everything Is Worse in China.’ That essay focused on conservative lamentations about American society, and made the case that almost all those issues are worse in the PRC. I noticed an oblique interconnection with something I’d written a few months ago, lamenting the financialization of America’s economy. I argued that the US is experiencing a sort of finance curse that is systematically undermining incentives to innovate and invest in the real economy.

So, is financialization worse in the PRC? The answer isn’t obviously no, which leads me to think it deserves investigation.

The Great Wall of Capital

I began my essay on America’s financialization with reference to FIRE—finance, insurance, and real estate. In the US, finance and insurance alone represent 8.5% of US GDP, as of 2017.

According to Yin Zhongqing, deputy director of the Finance and Economics Committee of the National People’s Congress, in 2015 finance and insurance represented almost 9% of the PRC’s GDP. So, right away, we can conclude: that problem is worse in China.

Yin went on to comment that:

“with the fast expansion of the money supply, vast volumes of funds have cycled back into the financial system, vast amounts of liquidity have never entered the real economy...and ‘casting off the real for the empty’ [脱实向虚] has grown more intense.”1

The deputy director has furnished us with a nice description of financialization, which can be more generally defined as profits accruing disproportionately via financial channels, such as interest payments or asset inflation, rather than through trade and commodity production. In places across the world,

“Retirement savings collected from households by institutional investors (such as pension funds and other SPVs), trade surpluses and sovereign funds), surplus money resulting from recent quantitative easing policies and the rise in accumulated profits of transnational companies in tax havens have all created a wall of money that gradually pushed for the financialization of built environment.”

In the PRC, finance and insurance pales in comparison to the main attraction: real estate. In 2013, former chief economist of the Agricultural Bank of China offered an official window into a general phenomena:

“Almost all big manufacturing companies have, to a certain extent, gotten involved in real estate. For many companies sales are stagnant, business is difficult, and the ability to earn a profit has sharply declined, so more and more manufacturing companies have started to subsidize their losses by getting involved in real estate or with financial investments.”2

Dinny McMahon’s China’s Great Wall of Debt burnishes this quote with several personal anecdotes of entrepreneurs in the PRC who, while ostensibly doing things such as running textile businesses, derive wealth and income primarily from real estate.

McMahon recounts one representative case:

“When Zhu [Shanqing] mentioned that he also ran a property-development business on the side back in China, I decided to check it out. I assumed it was just a hobby of sorts. I certainly wasn’t expecting the Keer Century Bund… The development included 360 villas—each with its own elevator and a dedicated room for a nanny or butler—and about a dozen apartment towers that lined the south bank of the Qiantang, the river that runs between Hangzhou and Xiaoshan. The sheer scale forced me to reassess Zhu’s business. Property wasn’t some side venture. This was the business.”3

This phenomena, that undergirding every entrepreneur’s ostensible business is actually a real estate empire, is captured well by an editor at Foreign Policy who quipped: the “first rule of Chinese business: Everything Is Actually Real Estate.”

Here is a high-level heuristic for thinking about the intersection of land, real estate, and financialization (the end of the essay specifically addresses the interconnected framework of the PRC’s property fueled financialization, but this graphic provides a quick overview that is worth scanning so you can better conceptualize what we’ll be diving into);

Awash In Savings

America’s financialization, as I wrote, is undergirded in large part by both a domestic savings glut of the rich and a global savings glut. This, in conjunction with neo-liberal policies that have led to an overall deflationary environment for real goods AND—especially in the last two decades—ultra-easy money policies, have created strong incentives to invest in *inflatable* financial assets. This led to what I snarkily called the Generalized Asset Bubble. I furnished a lot of evidence that this is indeed the case—and explains why inflation has stayed low despite consistently near-zero interest rates.

The PRC, meanwhile, is experiencing a similar issue—but for different reasons. McMahon again:

“ironically, as the economy slows, so should demand for financial services. But in China, they continue to expand, not because the real economy demands credit but because there is so much money that demands somewhere to invest.”

The PRC, like the US, has a savings glut. Key difference is that the PRC’s is almost entirely domestic (whereas in the US it’s 50% foreign and 50% domestic savings).

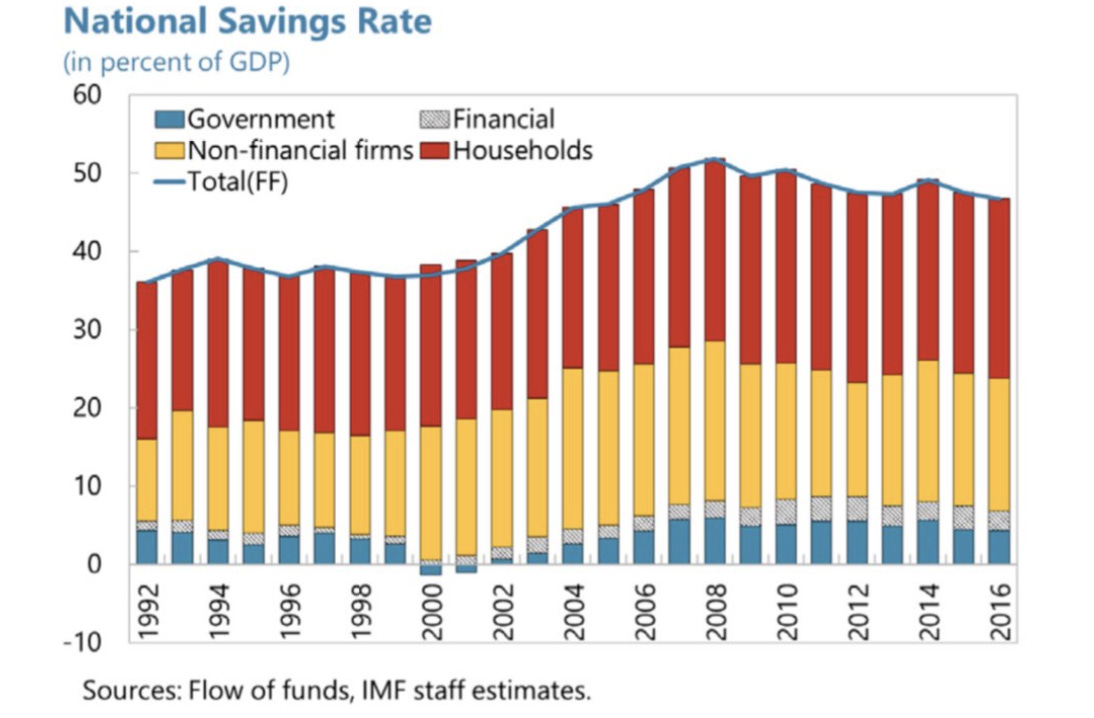

As the figure above from the IMF on the PRC’s national savings indicates, the vast trove of savings stem almost entirely from households and non-financial firms. The PRC’s savings rate, at roughly 50% of GDP, is among the highest in the world—and among G20 economies is by far the highest (for comparison, the US’ national savings rate is 14%, the UK’s is 18%, and Japan’s is 25%).

Similar to the US, it is also highly likely that the PRC is experiencing a savings glut of the rich. Unlike the rest of the world, however, every decile of the PRC’s income distribution has a very high savings rate—something that is not well accounted for in the literature that I’ve read (though the IMF pins most of it on the PRC’s demographic policies). But, very much like the rest of the world, and as can be seen from the graph below, the savings rate of the rich substantively exceeds that of lower income deciles.

Inequality & Savings Glut of the Rich

Meanwhile, again mirroring the US, income and wealth inequality in the PRC is quite extreme. Credit Suisse’s 2020 global wealth report estimates that the top 1% in China own roughly 30% of the wealth (vs 35% in the US).

Further, researchers Thomas Piketty, Li Yang, and Gabriel Zucman looked at inequality in the PRC and found similar results. They state that:

“China’s inequality levels used to be close to Nordic countries [but] are now approaching US levels.”

These comparative of graphs of the PRC’s evolving income and wealth distributions tell the tale:

Clearly many have revelled in Deng’s adage that it’s okay for some to get rich first. Although no study mirroring those on America’s ‘indebted demand’ and ‘savings glut of the rich’ have been done in the PRC, I believe the evidence strongly indicates that a similar phenomenon has been happening. One of the more obvious manifestations being the rise of wealth manage products that banks have set up on the low for rich clientele.

Deluge of Credit

Similarly, there has been an unprecedented expansion in credit. Logan Wright and Daniel Rosen have written extensively on the topic, and in a recent note in 2020 try to frame the stunning numbers in a comprehensible fashion. The PRC’s financial system

“has increased in size by 4.5 times since the global financial crisis, rising from 64.2 trillion yuan ($9.4 trillion) in assets as of the end of 2008 to 292.5 trillion yuan as of last month ($41.8 trillion). To put the current value in context, it represents about half of global GDP. In the same interval, China’s GDP roughly tripled in size, adding around $9 trillion in annual output.”

Here is the phenomena in graphic form:

The US banking system is $21 trillion. So, in terms of raw financial system size, that problem is worse in China.

Meanwhile, individuals in the PRC have grown increasingly indebted. As of 2017, household debt relative to household income was higher in the PRC than in the USA.

As a recent note from Rhodium Group says, “Over the past five years from 2015 to 2019, China’s households have added $4.6 trillion in borrowing, compared to a $5.1 trillion expansion in US household debt from Q3 2003 to Q3 2008.” As in the US, most household debt comes in the former of mortgage debt, “which the PBOC places at 30.1 trillion yuan ($4.3 trillion) as of the end of 2019, up from 11.5 trillion yuan ($1.6 trillion) at the end of 2014.”

In the PRC, as in the US, many families are increasingly leveraging up to invest in assets that they hope can only go up. Whether this problem is overall worse in China is not clear—more on that below.

Housing

So, we’ve seen that PRC citizens have high levels of savings at every decile, that inequality has increased and likely produced a savings glut of the rich, that the financial system has expanded massively (4x) over the last decade, and that families are increasingly levered up themselves. The obvious question, then, is where are all the savings and credit going? As McMahon states in China’s Great Wall of Debt:

“Most obviously it’s gone toward inflating asset prices.”4

In contrast with the US and other developed countries, though, the investment profile for the average PRC citizen is far more heavily weighted in real estate. According to most surveys, this asset class makes up roughly 80% of the average family's portfolio. In the US, by comparison, the figure is closer to 35%.

Thus, whereas in the US we may very well characterize the financialization regime as a Generalized Asset Bubble, in the PRC it’s really just a property bubble. And indeed this is precisely the story that the asset markets bear out:

As a recent report in the Wall Street Journal spells out—quoting from research done by Goldman Sachs—the PRC’s real estate market has ballooned to $52 trillion. That places it at 10x the size of its equities market, and nearly double the size of the US’s $24 trillion real estate market. Based on Goldman’s 2019 calculations, the three primary asset classes—real estate, bonds, equities— in the PRC have a total market value of roughly $70 trillion. In comparison, the US’s three primary asset classes have a total market value of roughly $100 trillion.

Further, a recent National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) paper measured the overall contribution of real estate to overall GDP in a slew of countries and found this:

Real estate in the PRC, inclusive of all the industries and services that support it, make up nearly 30% of GDP. That’s more than twice the percentage in the US. While this isn’t prima facie evidence of financialization, it’s intertwined with the increasing financialization of housing as an asset.

Why Such Allocation?

Rosen and Wright discuss the real estate situation in their 2018 report on the PRC’s credit situation, saying:

“There have been few meaningful corrections in China’s property market that have lasted longer than six to nine months, which has made it a powerful draw for household and corporate investors. China’s interest rates have been relatively low for years, and expectations that property prices will continue to rise have remained strong, increasing the incentive to invest.”

One of the most widely cited phrases on this issue is from Xi Jinping himself, who said

“Houses are for living, not for speculation.”

This is allegedly an indicator that the government is aware and on top of this issue. Xi has championed an innovation-oriented economic growth strategy, and as he and the Politburo undoubtedly know, increasing business and individual attention and investment in real estate—or mere asset appreciation generally—facilitates neither innovation nor factor productivity enhancement. In fact, it can systematically undermine TFP and innovation-oriented growth.

The problem, however, is the same issue that plagues the rest of the financial system in the PRC: rampant moral hazard owing to the—very credible—belief that Beijing will step in to stop downward market pressure. The CPC has routinely intervened to inject liquidity into banks, and has even intervened in the equities markets—halting trading and buying hundreds of millions worth of equity.

The property market in the PRC is more shot through with moral hazard than other asset classes, as local governments rely on land sales for roughly 50% of their revenue, as well as the value added taxes they receive from developers operations—not to mention, of course, the kickbacks local officials receive, often in the form of housing units. Meanwhile, because individuals in the PRC have 80% of their net worth tied up in real estate investments, a rapid decrease in housing prices would be a very scary prospect from a social stability maintenance perspective. There is thus a feedback loop wherein implicit guarantees and moral hazard induce more investment in real estate, which in turn induces greater moral hazard.

As in the US, there is a deep institutional and societal interweaving with the real estate market. However, the degree to which individual investors, local governments, and the major state-owned banks rely upon housing for revenue, financial assets, and collateral is completely disproportionate to anything in the US. From a real estate perspective, that problem is worse in China.

Relative Conclusions

So, is financialization worse overall in the PRC than the US? I don’t think any reasonable analyst could conclude that financialization on an absolute scale is worse in the PRC. But on a relative scale, I think there’s a strong case to be made that financialization is worse in the PRC. Keep in mind that nearly 50% of Chinese people still live on fewer than $10 a day. I can’t find a similar statistic for the US, but given that the minimum wage is $7.25/hr, it’s safe to assume that very few live on less than $10 a day in the US.

Further, the PRC’s median disposable household income is ~$4,000 (26,500 yuan) versus the US’s ~$36,000.5

The PRC has also received far, far fewer foreign capital inflows than the US—roughly $1 trillion in total foreign holdings compared to the US’s $20 trillion. Those numbers don’t include real estate holdings, for which the US receives additional hundreds of billions a year—much of which comes from the PRC itself and is hard to measure directly—which is multiples of the much smaller but rising rate of real estate inflows into the PRC.

The PRC’s asset bubble—across the three primary asset classes: real estate, equities, and bonds— is nonetheless 70% of the US’s. That the PRC has so much less wealth, and receives so much fewer financial inflows, only makes the market valuation of its financial assets more insane.

These statistics corroborate the narrative that the PRC’s own high level officials—quoted above—are saying. And also jives with what many economists have been saying for years: if state-led investment continues to crowd out private opportunities, and if a fundamental rebalancing of the PRC’s economy away from investment-led and toward consumption-led growth fails to materialize, economic opportunities will whither. We are, probably, already seeing the result: Corporations and individual investors—on the back of a deluge of savings and easy credit—are shoving money into a highly financialized real estate market laden with moral hazard, inflating valuations, rather than investing productively.

On a relative basis, then: financialization is a problem that also seems to be worse in China.

Addendum

I need to re-emphasize the population factor.

Perhaps the massive valuation of the PRC’s real estate market is simply what happens when the world’s largest population, newly enriched and boasting the world’s highest savings rate, directs almost the entirety of its riches into a single asset class. What’s more, the rapid urbanization of the PRC’s population surely further fuels this valuation bonanza. As a recent piece in Yale Politics points out:

“Urbanization—moving families from the countryside to the city—is critically important to understanding China’s housing situation,” Stephen Roach, a professor of economics and East Asian studies at Yale University told The Politic. And yet, that historic trend is barely mentioned in many articles from sources such as Bloomberg and the New York Times that discuss the coming collapse of China’s bubble.

Keep in mind, though, this piece is about financialization, not bubbles & crises. So the important point is merely that a profound amount of savings—from individuals and corporations—are being funneled into boosting property valuations rather than into other more productive types of investment. It’s entirely possible this isn’t a ‘bubble’—or isn’t best characterized as such. But it’s also even more plausible that this is not the best use, from the perspective of the PRC’s economic growth, for all these funds.

McMahon, China’s Great Wall of Debt, pp 133

McMahon pp 131

Ibid.

Ibid.

PRC Data | US Data: According to Our World In Data in 2013 US median disposable income was 16% below the mean. According to the OECD’s 2018 data, US mean disposable income was $42,300. Extrapolating, US median disposable income

Great piece! I think you might want to use the word "furnish" where you use the word "burnish." One means give, the other means polish.

You mention real estate is perhaps not the most efficient use of Chinese savings, but don't state why. I've heard this elsewhere but never heard a good alternative. China is already the world's factory, and the largest consumer of nearly every commodity. It has the largest car market in the world, etc, etc. It doesn't seem like the 'real' economy is choked of funding. From what I read, China still has a lot of work to do to catch up in a few select industries (microprocessors, industrial agriculture), but even there the bottleneck is likely human talent/knowledge, not capital. So at the end of the day, whatever gets more housing units built is probably a wise use of funds. Imagine if America 'overbuilt' before today's regulatory and cost bloat set in.