The Life and Times of Xi Zhongxun

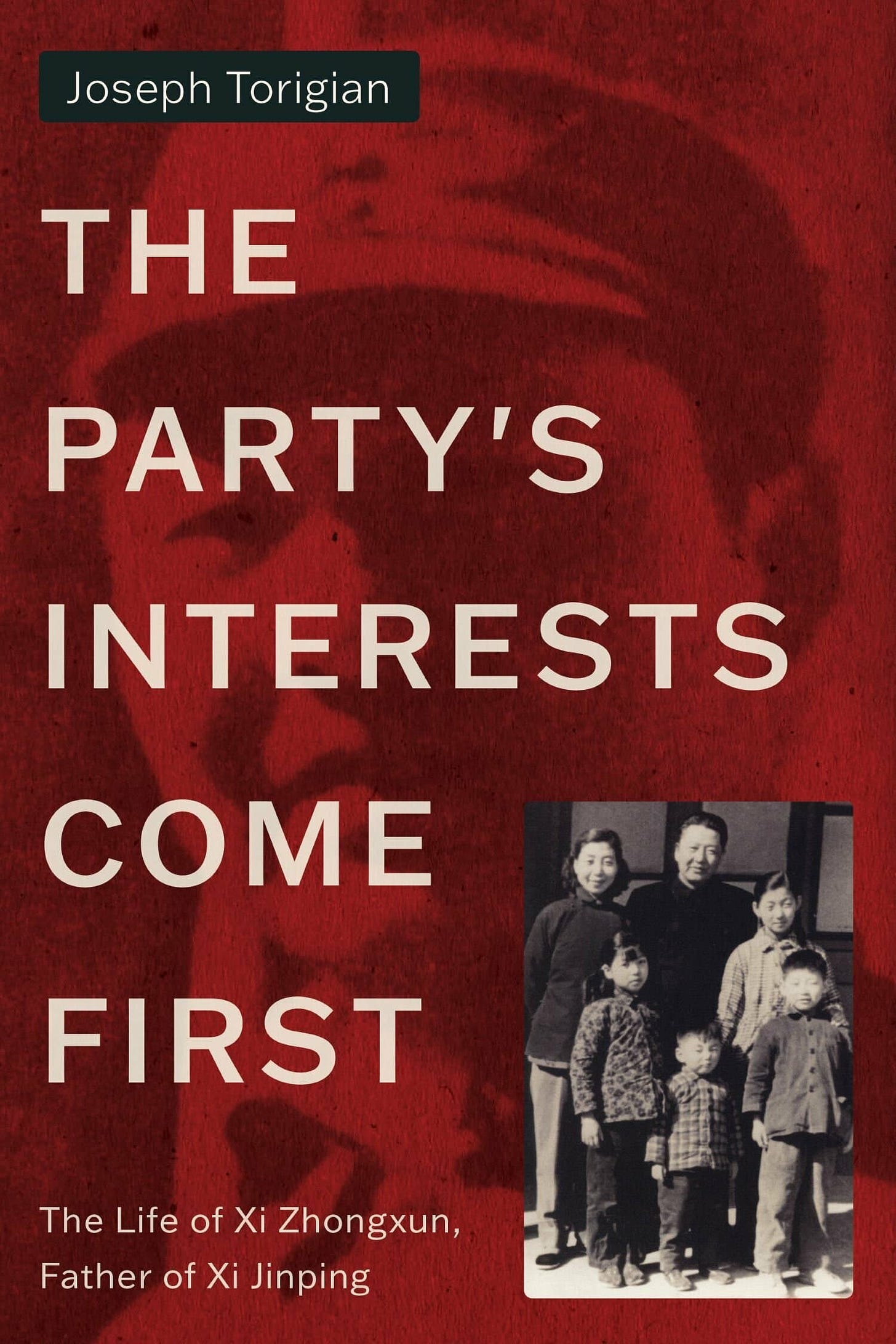

The Party’s Interests Come First, Joseph Torigian’s magisterial new biography

And Suffering Will Be Your Teacher

Xi Zhongxun was born into a fallen world. That, at least, is something the father and the son, whose youth was forged in the Cultural Revolution, have in common. But if we speak literally rather than metaphorically, the world of the elder Xi was not fallen, but falling apart. He was born in 1913, in the desolate northwest of China, as a scourge of European guns, germs, and steel was unleashing forces that would sweep the world’s great agrarian empires—Ottoman Turkey, Romanov Russia, and of course Qing China—into the dustbin of history. These same forces would pull Zhongxun, like so many young radicals of his time, into the dark vortex from which modernity would crawl. The birth of modernity in China was a bloody and terrifying upheaval. Anything, Mao quipped, but a dinner party.

Modern minds may struggle to comprehend the youthful Zhongxun. One could begin, as The Party’s Interests Come First does, with the shocking story of how he tried to murder his teacher at the tender age of 14. One could describe how famine stalked Zhongxun’s family, distending his belly and those of his orphaned siblings, claiming several of them. One could note that Zhongxun’s first wife was only eligible because her first husband had his head severed from his body by one of the various warlords and militias—and it was she, an eighteen year old girl, who had to find and bury the carcass.

Images of death and suffering have burst on to our social media feeds in the 21st century. For most of us they disappear as quickly as they arrive, a flash on the screen sent away by the next swipe of the finger. Inhabiting the mindscape of Xi Zhongxun is hard, perhaps impossible—it would require experiencing things we never have, lingering on them for more time than we are comfortable or perhaps capable. Terrible and turbulent days of unceasing insecurity, death, and suffering are mercifully, for most of us, foreign.

But Zhongxun and his revolutionary kin came to know suffering like a first language. It spawned in them a zeal for purpose and meaning; a drive to find something that could not only bring order to a chaotic present, but something that could redeem a fallen world, that could make sense of seemingly senseless suffering. Suffering shaped and inexorably drew people toward causes bigger than themselves. Toward things that, as Viktor Frankl would have understood, transformed the very meaning of suffering. For some, like Zhongxun, suffering became the crucible in which the meaning of their lives was forged.

There was nothing inevitable about Xi’s trajectory, however. Subjected to similar suffering, any number of men or women might have chosen a different path. For Xi, the road he walked was shaped as much by happenstance as by conviction—introduced to the basic concepts of communism, almost by accident, first by a teacher and then by an educated prison mate. As Torigian reveals in his prodigious excavation of Zhongxun’s life, Xi would later recall that he knew nothing of communism when he first joined the cause. It was not the Communist Manifesto, Lenin’s Imperialism, or any other Marxist-Leninist tract that first kindled his passion. It was his own suffering, reflected back to him in the pages of a novel: The Young Wanderer. “If other poets,” the author, Jiang Guangci, would write, “pride themselves on being artists ahead of their time—creators of beauty—then I pride myself on being a true son of the age, a singer of the storm.” Much as Stalin drew strength from Georgian heroic tales (from which he also took a nickname, Koba), Xi, too, found inspiration in literature. By chance and circumstance, his creed became the communist one, and his devotion was given to the Communist Party.

If Zhongxun’s conversion to the communist cause was shaped by chance and far from foreordained, it was also part of a larger pattern. Like the old Bolsheviks profiled in Slezkine’s House of Government, Xi was one of many youths who gave themselves wholly to a cause. And once he made that choice, he never wavered. The many bloody trials and tribulations he endured in service of the Party—the only force he genuinely came to believe that could save China—hardened a commitment that would prove unshakable. Part of this devotion was deeply personal. With both parents dead and little family to call his own, the Party became his surrogate kin. The “forging” he underwent in those early revolutionary years—from infiltrating the Nationalists in his teens and twenties, surviving multiple assassination attempts, to becoming one of the youngest pioneers of the northwest base where the Communists would eventually settle in Yan’an, a place where he would both purge and be purged—took on a fetishistic significance in later memory.

For many Chinese Communists, and revolutionaries the world over, suffering was their teacher. And it taught them that only total devotion to the cause, of which the Party was the sacred embodiment, could deliver salvation. A close reading of Torigian’s biography enables the modern mind to feel this.

Do Not Wait Until The Evening to See How Splendid the Day Has Been

As Torigian reminds us, Zhongxun is often remembered in popular conception as one of the most humane figures the Party ever produced—held up as a symbol of reform at its most principled, a legacy now sometimes invoked to cast Xi Jinping as an unfilial son who has betrayed his father’s path. But as Torigian painstakingly shows, Zhongxun defies easy categorization. The elder Xi’s life, Torigian writes, is “a powerful statement about the misleading nature of grand narratives” (page 535).

Xi the “reformer” initially opposed the household responsibility system. He despised materialism. He railed against the corrosive threat of individualism. As Torigian writes, quoting him intermittently:

“Individualism was a ‘germ.’ Even if small, this germ ‘does not fear the heavens, does not fear the earth, and it is extraordinarily daring.’ He continued, ‘Even if you weigh eighty kilograms, even if today you have only a tiny, tiny bit of individualism in your body, once it develops, it will devour you whole.’” (p. 194)

Zhongxun, for his part, routinely and enthusiastically affirmed his commitment to Deng’s Four Cardinal Principles. The tension between the “Three” and the “Four”—as Torigian frames it, the economically reformist spirit of the 1978 3rd Plenum versus the enduring imperative of the Four Cardinal Principles to uphold the Party’s authoritarian core—runs through the Party as well as Xi.

A Lighter Side to Xi Zhongxun: At Disney Land (1980)

Underlying it all is the deeper tension at the core of Zhongxun’s life—the conflict between humaneness (人性) and Partyness (党性)—between what one thinks is right and what the party demands or deems acceptable. Despite his difficult youth, Zhongxun somehow sustained a gentler, more conciliatory side. It was further honed through years working in the United Front, where he often favored dialogue and co-optation of local power brokers over coercion in dealings with ethnic minorities, religious groups, and other non-Party actors. One striking example comes from policy in Xinjiang, where, as head of the Northwest Bureau, Xi intervened all the way to the top to overturn a hardline approach pushed by Deng Liqun and Wang Zhen, figures typically cast as staunch conservatives. In doing so, he was willing to bear the enmity of Deng and Wang (which would surface in due time) so as to forestall a more repressive campaign against religious believers and nomads there, favoring instead a more peaceful strategy of co-opting and courting local power brokers.

And yet, as the aptly named book reflects, when the Party’s interests were on the line, they always came first. If the Party needed someone eliminated, Zhongxun would—and did—comply. As he did in Xi’an in the early 1950s, fulfilling Mao’s mandated execution quotas, and earlier still during the Shaanxi base area purges of the 1940s, when Xi was county secretary of Suide. Zhongxun also remained conspicuously silent during the Tiananmen crisis, despite holding the prominent, and at the time very relevant, post of NPC Vice Chair—perhaps shrewdly foreseeing Deng’s violent verdict and not wanting, once more, to end up on the wrong side of Party history.

A Tougher Side of Xi Zhongxun: His Portrayal In Hagiographic New 39 Episode Miniseries (2024)

The prodigious depth of Torigian’s research invites comparison with Robert Caro. In Working, Caro recounts a formative piece of advice from his early days: “Turn every page.” Across roughly 2,000 endnotes and an extraordinary range of Chinese-language sources, Torigian shows the same tireless commitment. His book is not only a biography, but a repository of primary sources and a work of translation, with many materials rendered into English in full or in part for the first time.

Amid the mosaic of sources, three stood out to me. First is Xi’s official Chinese biographer, Jia Juchuan, whose three-volume life of Zhongxun is thoroughly mined. Torigian describes Jia as “more likely to omit than mislead,” and his account is triangulated with other key works like The Chronicle of Xi Zhongxun (习仲勋年谱) and Biography of Xi Zhongxun (习仲勋传). Second is Li Rui—former Mao secretary and high-level Party insider—whose private diaries, now archived at Stanford, offer invaluable glimpses into elite politics. Torigian draws on them carefully to add texture and insight. Third is Warren Sun, a towering figure in Australian China studies. Alongside Fred Teiwes, Sun has long set the standard for rigorous political analysis, and has done more than most to recalibrate Deng’s legacy—as both architect of reform and calculating autocrat, including his role in sidelining the more consensus-minded Hua Guofeng.

But if Torigian’s research ethic recalls Caro, his narrative style diverges sharply. There is no luminous epigraph urging readers to “wait until the evening to see how splendid the day has been,” as in The Power Broker. Instead, contradictions are foregrounded, ambiguities embraced, and tidy storylines deliberately refused. This is a book that resists resolution. Considering how often—and for how long—both internal participants and outside observers have misunderstood Chinese politics, such caution is not only reasonable but necessary. So many statements must remain provisional, with multiple streams of evidence pointing in suggestive directions but rarely converging into certainty. Such are the realities of writing about a man operating at the center of a system that is built around secrecy.

One of the central lessons of The Party’s Interests Come First is that the familiar labels used in China-watching—reformer versus conservative, or more morally charged binaries like good versus bad—often collapse under scrutiny. Torigian dismantles these categories, showing how supposed heroes were less heroic than assumed, and villains less villainous. At the top of the regime, everyone was, at one time or another, sometimes simultaneously, a victim and a perpetrator. That is the nature of the Party system. No one’s hands are clean, though some are more stained than others.

Inside the Leninist Machine

A focus on the characteristics and pathologies of Leninist systems, central to Torigian’s excellent first book on succession in China and the USSR, remains at the forefront of The Party’s Interests Come First. This new work, however, offers a more intimate portrait of how easily one can misplay their hand in the murky world of Leninist power politics—a setting in which prestige, manipulation, and coercion prevail. The intentionally hierarchical design of these regimes makes them especially leader-friendly: the top leader reliably stands above the rules and norms, able to reshape them at will. As a result, institutionalization at the apex is exceedingly difficult, if not impossible. Even among the highest ranks, elites operate in an environment of profound opacity, often unsure of the core leader’s true intentions, the current alignment of political forces, or what must be said or done to maintain their position.

Twice in his career, Xi Zhongxun served as a chief implementer to the regime’s chief implementers: first under Zhou Enlai in the State Council of the 1950s, and later under Hu Yaobang in the Secretariat of the 1980s. In both roles, Xi witnessed firsthand how precarious elite politics could be. In early 1958, Mao turned sharply against Zhou for trying to moderate the Great Leap Forward (“Oppose Rash Advance”), stripping the State Council of its economic authority, creating five new small groups to oversee government work, and handing control over the economy to Deng Xiaoping and the Secretariat (who then presided over the most unrestrained phase of the disastrous campaign). Decades later, as a member of the Secretariat, Xi again observed how the Secretariat and the State Council, now under Zhao Ziyang, vied for influence, and how Hu Yaobang—often described as the conscience of the Party—was ultimately purged by Deng. Ironically, as Torigian determines, Deng repeated a pattern he had twice suffered himself under Mao: purging a deputy not for disloyalty or policy differences, but simply because his confidence in him had mercurially wavered (pp. 472–3).

The Old Revolutionaries, Before Their Scattering, On Their Way to Physical Labor

The much-touted “institutionalization” of Chinese politics under Deng Xiaoping is revealed as largely illusory. Torigian’s detailed reconstruction of events surrounding Deng’s autocratic and often arbitrary purges—of Hua Guofeng, Hu Yaobang, Zhao Ziyang (and, as an aside, nearly Jiang Zemin)—paints a far less orderly picture. Deng emerges, in the words of Li Rui, as “half a Mao”: a leader who deliberately preserved a two-line system that concentrated immense discretionary power in his own hands while leaving others to operate in a state of calculated uncertainty. When he did intervene, as in the decision to use force at Tiananmen, it was often abrupt, unconsultative, and final. In this light, elite politics under Xi Jinping appears less an aberration than return to form.

Throughout the book, Torigian revisits key inflection points in Party history: the fall of Gao Gang, the Great Leap Forward, the purge of Peng Dehuai, the emergence of the Special Economic Zones (SEZs), and the ouster of Hu Yaobang, among others. In each case, he draws on an extensive array of sources, often supplemented by anonymous interviews with insiders, to show just how easily both outsiders and insiders have misunderstood events. One striking example is the birth of the SEZs, where Hua Guofeng—alongside Xi Zhongxun in Guangdong—emerges as a central architect. Deng Xiaoping, contrary to the prevailing view, did not formally endorse the zones until relatively late in 1984, after their early success had become evident. “By then,” Torigian notes, “Deng was taking credit for everything. “I proposed setting up special economic zones,” he said. “It appears that the correct path was taken” (page 285). Western textbooks have since gone along with Deng and Party historiography in doing Hua a lasting disservice, reducing him to a caricature as the Maoist ideologue clinging to the “Two Whatevers,” remembered if at all through a dismissive throwaway line.

Factions play a surprisingly minor role in this account, in contrast to works like Victor Shih’s Coalitions of the Weak or Cheng Li’s earlier scholarship, which emphasize the role of patronage networks and elite affiliations. Patronage networks, often assumed to be relatively coherent, emerge here as more fluid and contingent. While factional analysis remains appealing—particularly because ties can be quantified through shared hometowns, schools, or bureaucratic overlap—Torigian shows that many presumed alignments, such as Xi Zhongxun’s with Gao Gang or Peng Dehuai, were overstated, misunderstood, even among Party insiders. Old networks did matter, but they were also often unreliable. Just as typical, power and alignment shifted through opportunism or convenience, as in the case of Ye Jianying’s unexpected role in restoring Xi Zhongxun and landing him in charge of Guangdong, and in the case of Wang Zhen who, despite the seeming historical enmity regarding Xinjiang policy, became the first person to speak up for Zhongxun’s rehabilitation in 1977 (page 251).

Ideology, too, comes in for scrutiny. The arbitrariness of ideological labels often obscures more than it reveals. Party leaders, like the institution itself, frequently held contradictory positions simultaneously. As today, this does not tend to produce dialectical synthesis so much as oscillation and confusion on the part of internal participants and external observers. Torigian is especially pointed in one aside: “Guessing about whether Jinping cares more about ‘ideology/security’ or ‘development’ is a distraction from the basic point that the Party has always cared about both, even though the pursuit of two such goals simultaneously inevitably creates tensions” (p. 543).

What It Is, And What It Isn’t

This is not a book about Xi Jinping—though, if judging by much of the popular media coverage thus far, one could be forgiven for thinking otherwise. There are, to be sure, sections that probe deeply into the younger Xi, most notably Chapter 21, Princeling Politics, which unearths fascinating details about his early rise through the Party in the 1980s. Torigian draws on sources affiliated with the Organization Department and the Young Cadre Bureau (a bureau responsible for identifying and fast tracking promising cadres) to reconstruct how Xi was perceived by contemporaries at the time, including revealing diary entries from Li Rui, who was then working in the OrgDep.

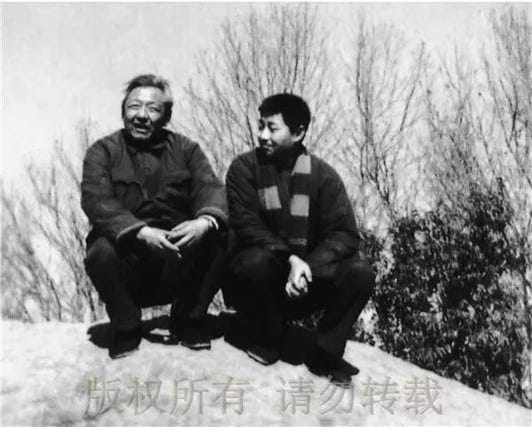

There are also moments of striking personal detail I had never encountered before—such as a scene near the end of the Cultural Revolution, when Xi Jinping visits his father in exile. In a sweltering apartment in Luoyang, where the elder Xi had been sent to labor in a tractor factory, father and son sit smoking cigarettes in their underwear as the younger Xi recites Mao’s speeches from memory, with Qi Xin watching.

The book does not examine Xi Jinping’s policies today, but it offers a window into how he has internalized his commitment to the Party. Jinping once spoke of confronting profound doubt during his years as a sent-down youth in Liangjiahe. But as with his father, it ultimately appears to not have shaken but deepened commitment to the party. Suffering, for him, became meaningful when understood as a sacrifice. His father never abandoned his loyalty to the Party, despite being purged over a novel, spending sixteen years (1962-1978) in the political wilderness, and suffering greatly during the Cultural Revolution. Torigian counsels: “While some may wonder why Jinping would remain so devoted to an organization that severely persecuted his own father, perhaps the better question is, How could Jinping betray the Party for which his father sacrificed so much?” (p. 539).

Xi Zhongxun and Xi Jinping in Luoyang (1975)

Finally, beyond Xi Jinping, the book is not even best understood as a biography of Xi Zhongxun. Its deeper purpose is in using Zhongxun as a lens through which to examine the history and internal contradictions of the Chinese Communist Party itself. What the book delivers is not just a portrait of the man who fathered China’s current leader, but a window into the moral and political structure of the Party that shaped them both.

Forging Red Genes

If there is a single throughline in Xi Zhongxun’s life, it is this: devotion to the Party above all else. The forging of loyalty through suffering did not remain his legacy alone. It reverberates in Xi Jinping’s own mythology as well. For both father and son, “struggle” and transformation into a loyal cadre take on a near-fetishistic significance, each held up as a model of what a true revolutionary should endure, and ultimately become.

Yet, as Torigian warns, there is no determinism in this process of forging. There is no guarantee that those who “suffer for a cause” emerge more committed. Just as easily, they may come out disillusioned, embittered, or broken. Zhongxun’s own children illustrate this variance: one committed suicide, one became a rule-of-law advocate, several chased money and pleasure, and one pursued power. Xi Jinping may have internalized his father’s legacy—may even have “inherited the red genes”—but the real cliffhanger is whether the next generations can or will.

This remains a central quandary for the Communist Party today: how to cultivate loyalty through struggle in an era defined not by war or revolution, but by peace and development, and how to do so without alienating the very people it seeks to inspire. In China today one frequently encounters the slogan 永远跟党走—“Forever walk with the Party.” But one finds it hard to imagine that China’s increasingly urbane, educated, and independently-minded elite dream of goose-stepping into eternity.

One wonders if Xi Jinping sees the germ of individualism spreading, as his father once did, threatening to devour the party whole. In 2017, a new slogan was popularized: 幸福都是奋斗出来的—“All happiness comes from struggle.” But what kind of meaningful struggle do today’s rising cadres face? What crucible of hardship might shape them into passionately devoted party members, as it once did their leader? And to what lengths might Xi be willing to go to find out?

Coda

Be warned: Torigian’s is not a beginner-friendly book. Readers unfamiliar with the terrain of modern Chinese history or the historiography laid down by earlier giants like Roderick MacFarquhar, Ezra Vogel, and Richard Baum may find themselves overwhelmed by the detail, unsure of the stakes, and unaware of previous interpretations in the field. Likewise, media headline writers and soundbite chasers will find little to grasp onto—and what they do seize upon, as early evidence indicates, may not well reflect the book’s actual content. Torigian refuses sweeping statements, brash generalizations, or seductive narrative arcs. “In many cases,” Torigian writes, “the vagaries of evidence and intention simply cannot bear the weight of the big questions we would most like to ask” (page 536). But those willing to forge insight and meaning out of complexity, contradiction, and contingency will likely recognize The Party’s Interests Come First as a major achievement—one of the finest works on China in the past decade, written by one of the greatest American China scholars of his generation.

Thank you for this inspiring review! Torigian's extraordinarily deep reading in Chinese sources impressed me too. I haven't gotten past page 200 yet. I have been getting sidetracked into the many issues that Joseph Torigian raises.

I ended up reading 'The Young Wanderer' and then doing a full translation on my blog: 1926: Full Translation — Jiang Guangci’s ‘The Young Wanderer’ — Xi’s Dad’s Favorite Revolutionary Book https://gaodawei.wordpress.com/2025/05/25/1926-full-translation-the-young-wanderer-xis-dads-favorite-revolutionary-book/ and some articles and books by Xi Zhongxun's contemporaries and more recent articles about Jiang Guangci that I have been able to find online.

It struck me too how 'The Young Wanderer' could be such and impactful book but get panned by modern literary critics. Maybe the same difficulty in understanding an immensely chaotic and cruel period make it hard to have the sympathetic understanding that would make 'The Young Wanderer' more appreciated.

Great book and great review.

Factions could be important (e.g., Red 4th Army Front veterans). But in case of Xi Zhongxun, the leader of the would-be faction - Liu Zhidan, Xi Zhongxun's mentor and second father, had died too early (and there was far too much infighting among the Northwestern veterans).