Atomization and the Future of the CPC

"Despite four hundred million people gathered in one China, we are, in fact, but a sheet of loose sand [yipan sansha (一盘散沙)]. We are the poorest and weakest state in the world, occupying the lowest position in international affairs; the rest of mankind is the carving knife and the serving dish, while we are the fish and meat…If we do not earnestly promote nationalism and weld together our four hundred millions into a strong nation, we face a tragedy–the loss of our country and the destruction of our race." — Sun Yat-sen

"Loose grains of sand cannot be tolerated" — Chiang Kai-shek

"It is only through the unity of the Communist Party that the unity of the whole class and the whole nation can be achieved, and it is only through the unity of the whole class and the whole nation that the enemy can be defeated and the national and democratic revolution accomplished." — Mao Zedong

“Government, army, society and education — east and west, south and north, the Party leads all” — A Mao era phrase now quoted by Xi Jinping

Our mission "requires all the Chinese people to be unified with a single will like a strong city wall.” — Xi Jinping's vision, as he told “the broad masses of youth” in his Labor Day speech of May 2015

“We must unite the 1.4 billion Chinese people into a majestic and boundless force driving the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” — Xi Jinping, in 2021 at the Party History Study and Education Mobilization Conference

Atomization

If you want to understand the most important challenge facing the Chinese Communist Party (CPC) you should read The True Believer by Eric Hoffer. The book is a magisterially concise diagnosis of what fuels, energizes, motivates, and guides mass movements. The most important challenge for the CPC—or rather what top cadres believe is their most pressing challenge—is keeping the Party organization and its 90 million cadres singularly united and faithfully committed in the face of drastic change, internal and external.

Modernization uproots tradition. The material economic conditions of modern free markets— capitalism—create a political economic environment that up-ends traditional social structures, whether families, large clans, or lineage organizations. Children move away to big cities and marry and live outside their close families, wives become increasingly independent, and the incentives created by marketization pull people further and further apart from one another. The result is atomization.

A key, perhaps the key test, for the Chinese Communist Party lies in its continued response to this enduring phenomena.

The Chinese Communist Party is striving to maintain its ability to absorb atomized individuals into a coherent organization that gives them a sense of belonging and their life a sense of meaning and purpose. It was, in fact, this historic capacity of the Party to co-opt individuals and direct mass movements that explains its ability to defeat the Nationalists in the Chinese civil war. Schell and Delury highlight this in their book Wealth and Power: "[Chiang's] authoritarianism was closer to that of traditional Chinese secret societies than mass-based political organization. In this and other ways, Chiang proved incapable of truly promoting mass political organization, an art in which his rival and nemesis, Mao Zedong, would prove the master" (Wealth and Power pp 193).

Going forward, the question is how well this core competency of the CPC can continue.

As organizations grow, it is increasingly difficult to maintain an intense sense of mission and belonging. Yet the deep yearning to live for something more than ourselves—to lose ourselves in a tribe dedicated to a greater good—doesn’t fade. This yearning, heightened by atomization—itself wrought by marketization and the breakdown of traditional social structures—can manifest in the desire to join new mass movements and new organizations. For the Party, now going on 40 years of reform and opening, this is a great concern.

Free Radicals

The atomization process was poignantly on display with the Falun Gong. As individuals at state-owned-enterprises, particularly in the Northeast, were thrown out of jobs and lost their sense of community, many turned to a variety of new spiritual organizations. One of these was Falun Gong. The quickly creeping size of this group, and the camaraderie and purpose its members felt, came to be experienced by the CPC as a direct challenge to its hegemonic authority. Falun Gong had to be reigned in.

The challenge of increasingly atomized individuals searching for belonging stretches beyond the Falun Gong. It can be seen in the rising rates of Chinese converting to Christianity, in Buddhist revivalism, and where possible the continuation of familial worship practices. The Party-state has directly responded by attempting to co-opt all such non-Party routes to solidarity and belonging, correctly recognizing such social organizations as potentially grievous threats to its monopoly on social power. On the peripheries, where minorities are even less entwined with the Party-state structure, the draconian crack downs are far more intense. The CPC has sensed the danger to its territorial integrity stemming from the organizational challenge to its monopoly on social power and cracked down ruthlessly.

At the same time, the Party has also become innovative in ways to try to capture these free radicals—the increasingly atomized Chinese citizenry. Most importantly, Jiang Zemin introduced the three represents to expand the realm of inclusion and goad more and more people into the Party structure. Xi Jinping, of course, ran with—though, importantly, did not originate— the discourse of the China Dream and the Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation. He did so, I would submit, to attempt to further induce people into a sense of group mission and belonging within the confines of the Party’s developmental monopoly.

Xi Jinping

Perhaps the most formative early influence on Xi came when he was sent to the caves of Liangjiahe, Shaanxi province, at 15. Isolated from his friends and family, this was when he became a true believer. It is in the depths of isolation and atomization, after all, that people become most susceptible to indoctrination—and most willing to joining mass movements. Xi was no different. He left the caves 7 years later with a conviction that the solidarity offered by the CPC as organization was the key to China’s future. This would become apparent throughout his career. Not only a Party man, he even went to Tsinghua for a PhD in ideology and Party organization. He then went on to head the Central Party School, the lynchpin organization for instilling Party collectivism and discipline.

Chairman Xi is emblematic of an individual who understands the challenge the CPC faces. Indeed, it speaks to the awareness that top level cadres had of this emerging trend of atomization that they fast-tracked him for General Secretary. Xi became imbued with devotion to the cause—devotion to the Party structure—from a young age. He was both weary of the Cultural Revolution’s fanaticism, owing to the detrimental impact it had on his family and himself, but also greatly appreciative of his trials and tribulations. As Viktor Frankel reminds us in Man's Search for Meaning, "suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning, such as the meaning of a sacrifice.” For young Xi, it would seem, the meaning to be found in his suffering—the thing which he would come to sacrifice the great majority of his life endeavoring to fulfill—was carrying on his father's legacy of building a powerful, united, and mission driven Communist Party.

Xi Jinping is a man who believes that holding the Party together—imbuing its member with a sense of ideological faith, belonging, mission, and purpose—is the single most important thing in the world. More important than development, more important than eradicating poverty, more important than his own well-being. This is because he believes the Party is the key to all those things.

In a way, Xi Jinping is as any True Believer who understands how to keep his movement alive. Atomization of individuals is the dough with which mass movements are created. If the Chinese Communist Party is unable to mold proliferating free radicals into loyal cadres, the Party itself faces a grievous threat. Thus if the Party is unwilling to abandon the marketization process that creates atomization, it must increase its capacity to productively co-opt free radicals.

The Real Challenge

The much-prophesied fall of the CPC at the hands of growth slowdowns or even financial collapse are thus overblown. The analysis that leads to viewing these as the key factors of regime failure is misplaced. The most important thing that leads to regime failure is the inability to productively co-opt atomized individuals. When individuals cease to identify with the larger whole of the Party, when they cease to believe in the mission, and when they cease to believe in the movement. This is also why it is misplaced to focus emphasis on the specifics of the ideology. Any belief system will do, in fact, so long as the sense of tribalism and belonging is maintained. A coherent ideological belief system is as problematic to this goal as it is beneficial. Too coherent of an ideology risks being disproven. The one that tends to stick is one that is both sweeping yet capacious and able to adopt a multitude of beliefs. This is how Catholicism evolved, and it is how Marxism-Leninism in China has evolved. Marxism-Leninism in China keeps the shell of the belief system—most importantly Lenin’s contributions regarding a vanguard Party—but has cleared out its innards. And while it is true that slow-downs in growth and financial instability increase the discontent of atomized individuals and thus the risk to the Party, so long as the Party can has effectively co-opted most of these individuals and no other coherent movement exists to channel their grievances, the Party will carry on unmolested.

This, however, introduces us to the risk the CPC’s attempts to co-opt these individuals may pose to the rest of the world. We have seen that as lineages evaporate, atomized individuals in China proliferate, growth slows, and financial instability due to marketization grows, the CPC faces ever more pressure to effectively co-opt Free Radicals. This can and does take the form of repressing alternative movements, as well as increasing recruitment into the Party and increasing the sense of belonging and mission for those in the Party structure. While the former may be devastating for those within China’s borders (e.g. Xinjiang), it is the latter that poses a global challenge. How China goes about inculcating a sense of unity and belonging amongst its expanding (90 million+) rank and file has transnational implications.

Consider, analogously, the current ramifications of the debate over the Narrative™ in America. Many people want to hue towards the traditional American Narrative™ of exceptionalism that conspicuously minimized wrong-doing while emphasizing the importance of patriotism—the Trump Narrative™. Meanwhile, others want to forward a Narrative™ that paints America has little else but white supremacy, oppression, and false promises—the extreme woke Narrative™. Neither one is correct, in fact no singular Narrative can ever be correct (though the truth, as they say, is likely somewhere in the middle). The important point, though, is that the Narrative that becomes ascendant will have important implications for domestic political milieu as well as its behavior overseas. A Narrative™ is a critical part of how a nation holds itself together, how the masses are motivated to identify with the nation and push their elites to make policies, and ultimately how elites create and enact domestic and foreign policies.

As in the US, the Narrative™ that China adopts is critically important for its future trajectory. While a Narrative™ is itself a necessary device for holding the Chinese people together and is more or less interchangeable, the specific content of the Narrative also has specific consequences. A Narrative can be more or less bellicose, for example. The Party can locate its sense of meaning in the Narrative™ by explaining prior conditions as acts of suffering imposed by others—the West, for example—and thus locate itself as a gallant savior and redeemer of the Chinese people. The Party can further nurture a sense of injury and grievance, creating within Free Radicals (atomized individuals) a reflexive disgust and hatred of Western countries and a reflexive belief in the goodness—and feeling of solidarity with—the Chinese Communist Party, who is the one and true represent of the Chinese people and, of course, can never be separated from them. At the same, the Party can create the ‘long hope’ that a community of common destiny, forged principally by the CPC, will work to the benefit of all—especially the Chinese people—and so everyone should join in and support the Party in this great mission that socialism with Chinese characteristics is about to take us on.

It is too early to know how things will play out. But the hyper nationalism of online commentators, the hawkish nationalistic sentiment expressed by youth in major Chinese cities, the various militaristic outbursts in the South China Sea and on the Indian border, and the Wolf Warrior Diplomacy would seem to offer a troubling premonition. Indeed, on more than one occasion, the Chinese Communist Party has had to specifically reign in anti-foreign protests that were getting out of hand—lest they grow into something beyond the Party’s control. But the tenor of the nationalist outbursts is indicative of a successful patriotic education campaign that inculcates a belief in China as victim and other countries as abusers and bullies. A victim mentality, as Cory Clark at Quillette has well summarized, can induce a sense of righteous aggrievement that justifies one’s own heinousness. As I’ve written recently, the path to hell is paved with righteousness. Perhaps these are overblown cues. Only time will tell for sure.

Ultimately, though, the Party cares less about these unpredictable future consequences than it does about shoring up its power and control in the here and now. From the beginning, the CPC was a mass movement organization and Mao Zedong was an innovative pioneer in engineering successful mass movements. This is what Xi Jinping takes away from Mao. Xi Jinping and the CPC’s other leading cadres all understand that co-opting the proliferating mass of atomized Chinese individuals is the most important task it faces. If it fails other movements will rise, and the CPC will face grave threats. But if Xi and the CPC can update and utilize Mao’s mobilization techniques, and if they can manage to burnish an increasingly market-based and atomized Chinese society with a collective sense of belonging and mission under the stead of identification with the CPC, they will live on.

The Intellectuals

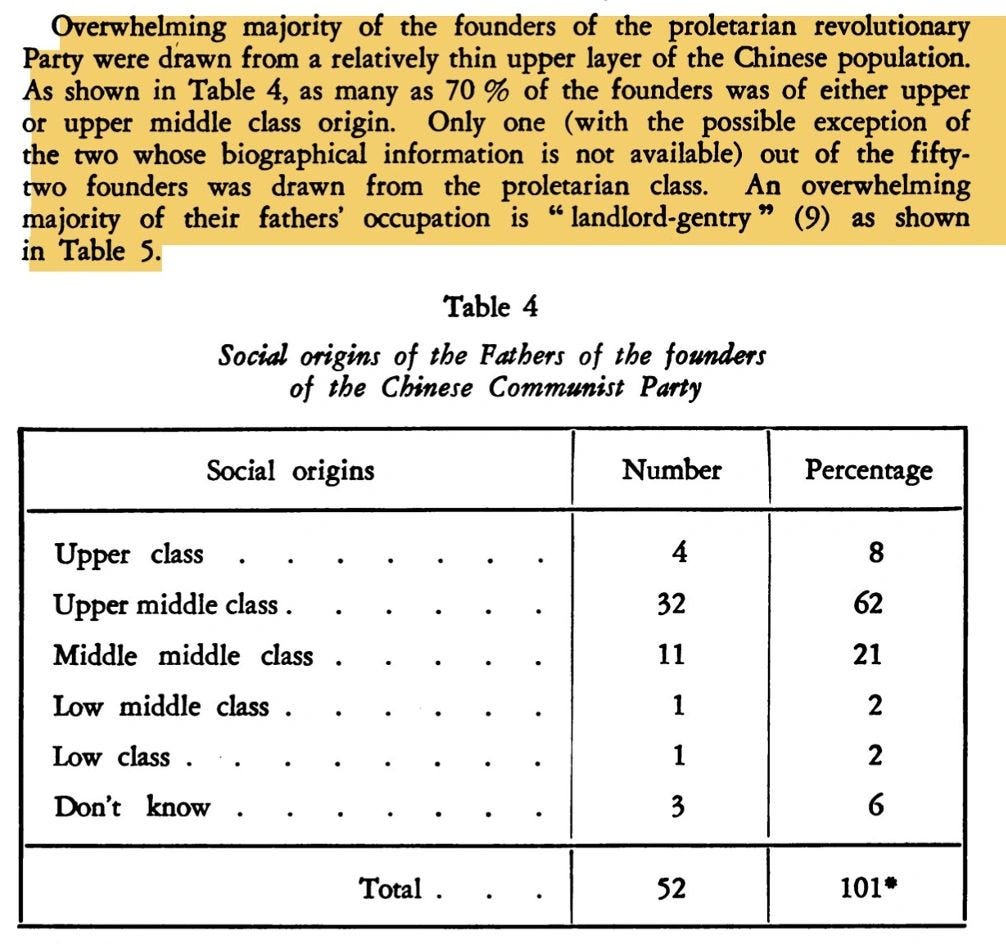

As this narrative overview suggests, the Party has an expansive apparatus for ingratiating itself with the increasingly atomized Chinese populace. In particular, the elite and sub-elite stratum. It is of interest that it was precisely this stratum that formed the Party in the first place. The Party thus has institutional memory of how disruptive an unattached group of sub-elite, atomized individuals can be. As a 1968 study on the early composition of the CPC concluded:

Thus today the Party appreciates how important it is to get this leading edge of the atomized free radicals into the confines of the CPC—where they can be safely co-opted and guided into service of the Party itself. Such is the goal of a fully institutionalized Leninist Party apparatus. To consume that base of society which it knows full well—due to its own experience as an under-dog, under-ground, anti-system organization—can destabilize an organization. Nadege Rolland describes the history in a recent report on co-opting the intelligentsia. Here's the essential part:

"The development of think tanks in China has largely adhered to an academic tradition of subordination to or dependence on the state. As in Soviet Russia, China’s research centers were from the 1950s onward directly controlled by and attached to the Communist Party or the state bureaucracy, including specific committees, ministries, and security agencies. But neither Mao Zedong nor Deng Xiaoping ever relied on them to inform their decision making. In the 1990s, Beijing allowed a small degree of openness, which led to the formation of a limited amount of civil society organizations and nongovernmental academic centers, mostly dedicated to research on economic issues. In the mid-2000s, CCP leader Hu Jintao, who had been president of the Central Party School, started to encourage input from Chinese intellectuals and experts to support policymaking, and regularly invited them to give lectures at Politburo Study Sessions. Several new and allegedly nongovernmental research centers, such as the Center for China and Globalization and the Charhar Institute, emerged during the 2008–2009 global financial crisis. Rather than offering genuinely independent perspectives on issues ranging from economics to international relations, the entities were established to create a false impression of opinion pluralism under increasingly tight ideological control from the party-state.

Xi Jinping’s rise to power in 2012–2013 marked in many domains an acceleration and clarification of previously observable trends. Think tanks are no exception. At a December 2012 CCP economic work conference, Xi proposed establishing high-quality think tanks to serve policymaking. A year later, the third plenum of the Eighteenth CCP Congress passed a resolution to create “new types of think tanks with Chinese characteristics.” Rather than inaugurating a flourishing new phase for independent Chinese think tanks, Xi’s policies were intended to further tighten government controls. Beijing passed laws restricting foreign funding for domestic nongovernmental institutions, and required that each think tank be placed under the strict purview of party-state entities. Fu Ying, a distinguished Chinese foreign policy practitioner, explained that Chinese think tanks should “adhere to the Party leadership and serve the country” while at the same time being “independent and objective.” In this case, “independence” does not mean free from government control, but rather free from the influence of Western concepts and ideas that the CCP considers threatening and subversive. More autonomous organizations, including the widely respected Unirule Institute of Economics, have since been forced to close down. The Unirule Institute of Economics—which had actively promoted China’s economic liberalization since its founding in 1993 and had tried to carve out a genuinely autonomous space for itself in an increasingly constricting environment—was locked out of its office in 2017 and eventually forced to close in 2019.

Xi remains committed to transforming Chinese think tanks into instruments serving the policies of the party-state, and he specifically demands that they help expand the regime’s international influence and contribute to the realization of its main strategic objectives."

Roland concludes: "In China, most think tanks are either built into or closely affiliated with Chinese Communist Party (CCP) organs and government agencies. Their research topics are framed by detailed guidelines and oriented to reflect governmental priorities."

As a recent report on the CPC's United Front Work Department (an organization tasked explicitly with co-opting individuals and groups outside the traditional confines of the CPC) further argues, the focus on bringing domestic students, overseas students, and intellectuals into the Party's orbit and making them amenable to its influence is strong is a core competency.

The reason for this focus is simple: free-floating, atomized intellectuals with a bone to a pick are dangerous. They can provide the guidance needed for new and destabilizing mass movements to spring up. They can mobilize the increasingly atomized Chinese populace. The CPC recognizes that the most sustainable way to deal with these intellectuals is to co-opt them. Under Maoism, more were killed than co-opted. Today, it's the other way around (though some who engage in really wrong types of activities are indeed killed—or 'disappeared'). Most importantly, co-opting intellectuals into a positive endeavor—e.g. theorizing about how to make China great again—serves as bulwark against invasive and threatening Western values. An unattached Chinese intellectual is far more susceptible to being 'infected' with the 'virus' of the Western values than one productively employed fortifying the CPC's ideological and intellectual base.

Furthermore, as Bruce Dickson, Andrew Walder, and others have shown there are substantial economic and network benefits to joining the Party. Not just for the intellectuals, but for the masses in general. For those who avoid the Party, meanwhile, there is effectively a glass ceiling when it comes to governmental appointments, appointments in SOEs, scholarly appointments and funding in think tanks and leading universities, and even in some private sector organizations. The CPC wants to make it desirable, from a status and wealth perspective, to be a member. This creates pervasive, impersonal forces that effectively attract free radicals into its fold, neutralizing their potential to join non-Party social structures that could pose a challenge to its monopoly on social power. (As I’ve written about regarding Entrepreneurship in China, though, co-opting the private sector has a tendency to run up against innovation, as the expansion of the Party and the stability it desires is hard to square with an innovation / creative destruction oriented ecosystem.)

Handling the growing problem of atomization is the CPC's greatest challenge. They are well aware of this. That is why they have created a massive infrastructure for co-opting these free floating radicals. In particular, the most dangerous ones: particularly the intelligentsia but also increasingly the business leaders. To ensure their sole monopoly as a center of social power and influence, the CPC is going all in on its ability to productively co-opt these atomized individuals. A China scholar described the CPC's authoritarian resilience as stemming from its representation within bounds, i.e. attempting to maximize informational benefits while minimizing reformist elements. Another way of formulating this is 'co-optation' within bounds. Those atomized free radicals who can be productively brought into service of bolstering the CPC will be. Those who cannot, well...